By last April, I had gotten in the habit of dragging a rocking chair out onto the thin concrete rectangle that made up the patio at my old apartment and spending my days reading in the sun. We had been pulled out of school in early March and my program was still figuring out how to conduct class online for a bunch of teenagers with spotty internet access. So most days I had very little work to do.

It was on one such sunny afternoon—April 7th, a year ago today—that I put down my book and went for a run. Midway through I opened up my phone to change the song and saw a text with the news that John Prine had died of complications from coronavirus, which he and his wife Fiona had both tested positive for two weeks earlier.

I remember feeling staggered. It had been nerve-wracking, knowing that he had it, but a few days earlier his condition had been upgraded to “stable,” which seemed like a glimmer of good news. And then he was gone. I have never really been one to mourn celebrity deaths, not because I am heartless or think myself above it all but because with the ascension to celebrity status comes a remove from the affairs of regular people, a dehumanization with blurry lines. I never know quite what to make of it. But John Prine’s death felt different: raw and real and earth-shattering. (He was also the first famous American to die from COVID-19, which probably helped bring it home.)

I wrote at the time about how much his music had meant to me when I discovered it during an exceedingly lonely and confusing time in my life. I wrote about how his legacy contained within it the exceedingly rare act of using his own talents to make space for others to shine. All these hundreds of thousands of deaths later and that gift feels even more real and important.

Lately I’ve been thinking about how extreme wealth is no foundation for a worthwhile life. I have no desire to fetishize struggle or fall into the trap of equating poverty and virtue, but in my experience, lives that drip with money from the jump tend to deprive their owners of the ability to really feel or savor much of anything. If everything is available to you, what joy can any of it bring? It would be pitiable if they weren’t in turn depriving the rest of us of so much.

John Prine surely made gobs of money over the course of his half-century as a performing musician. But long before that point, he was a regular working man from a working family, a union mailman and Vietnam-era army draftee. That regular life, decades away from any trappings of wealth, made him able to write songs that captured true feeling and deep human connection. I’m not sure any American songwriter ever paid more attention to the people around him. Even as a young man he showed a remarkable talent for empathy: he penned one of his most famous tunes, “Hello in There,” at age 22, capturing in song the struggles of the elderly to remain loved, cared for, noticed.

Prine said of his inspiration for that particular song:

I delivered [the newspaper] to a Baptist old people’s home where we’d have to go room-to-room, and some of the patients would kind of pretend that you were a grandchild or nephew that had come to visit, instead of the guy delivering papers. That always stuck in my head.

The triumphs and tragedies of everyday people interested him until the end of his life. “Summer’s End”, from 2018’s Tree of Forgiveness, tells a non-specific but universally recognizable tale of addiction and loss.

Well you never know how far from home you're feeling

Until you watch the shadows cross the ceiling

Well I don't know but I can see it snowing

In your car the windows are wide openCome on home

Come on home

No you don't have to be alone

Just come on home

His voice was instantly recognizable—as raw and full of feeling as the man himself. (Jason Isbell, in the obituary he penned for The New York Times, wrote: “When John developed squamous cell cancer on his neck in 1998, his doctor told him he might never be able to sing again. John told him, ‘Doc, you’ve never heard me sing.’”) Which is not to say that his voice was hard to listen to. Roger Ebert stumbled across a then-unknown Prine playing in a bar in 1970 and was so taken that he penned a review of the music for the Chicago Sun-Times the next day despite being a movie critic, not a music writer.

He appears on stage with such modesty he almost seems to be backing into the spotlight. He sings rather quietly, and his guitar work is good, but he doesn't show off. He starts slow. But after a song or two, even the drunks in the room begin to listen to his lyrics. And then he has you.

Even his sillier songs are spellbinding, because they almost all cut to the heart of something much deeper. The narrator of “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore” gets so overcome with patriotism while browsing the selections in a porn shop that he ends up covering his windowshield in American flag stickers, which causes him to die in a one-car crash. As the title suggests, he’s ultimately turned away at the Pearly Gates: heaven is already at capacity, having been filled up during the America’s most recent “dirty little war.”

This was not a man who averted his eyes from the world around him—quite the opposite. And in daring to look full in the face the people and events America would have liked to forget, he inspired millions to think and love a little harder.

As I have written before, this newsletter is often just a space for me to point things out, a way to log the connections and coincidences of my own thoughts and feelings. So it is perhaps fitting—in my own life, at least, I don’t claim to speak for either man—that the day after John Prine died last year, Bernie Sanders called an end to his presidential campaign, doomed by the closing of ranks behind Joe Biden by every other major candidate.

All the grief and uncertainty of last spring came crashing down on me in those two days. Everyone probably has their own moment or two where coronavirus first felt “real”; that 24-hour stretch was mine. Losing one of the best chroniclers of what ailed us and then losing the best hope we had in decades to fix it, back to back, was almost untenable. I wept a lot of bitter tears alone on the couch that week.

The last year has brought incalculable loss, most of it avoidable and preventable, if only we lived in a different world. But of course we don’t: we live in this one, the world John Prine sang about. I don’t know where the next prophets and fighters will come from. I just hope we listen harder when they take the stage.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

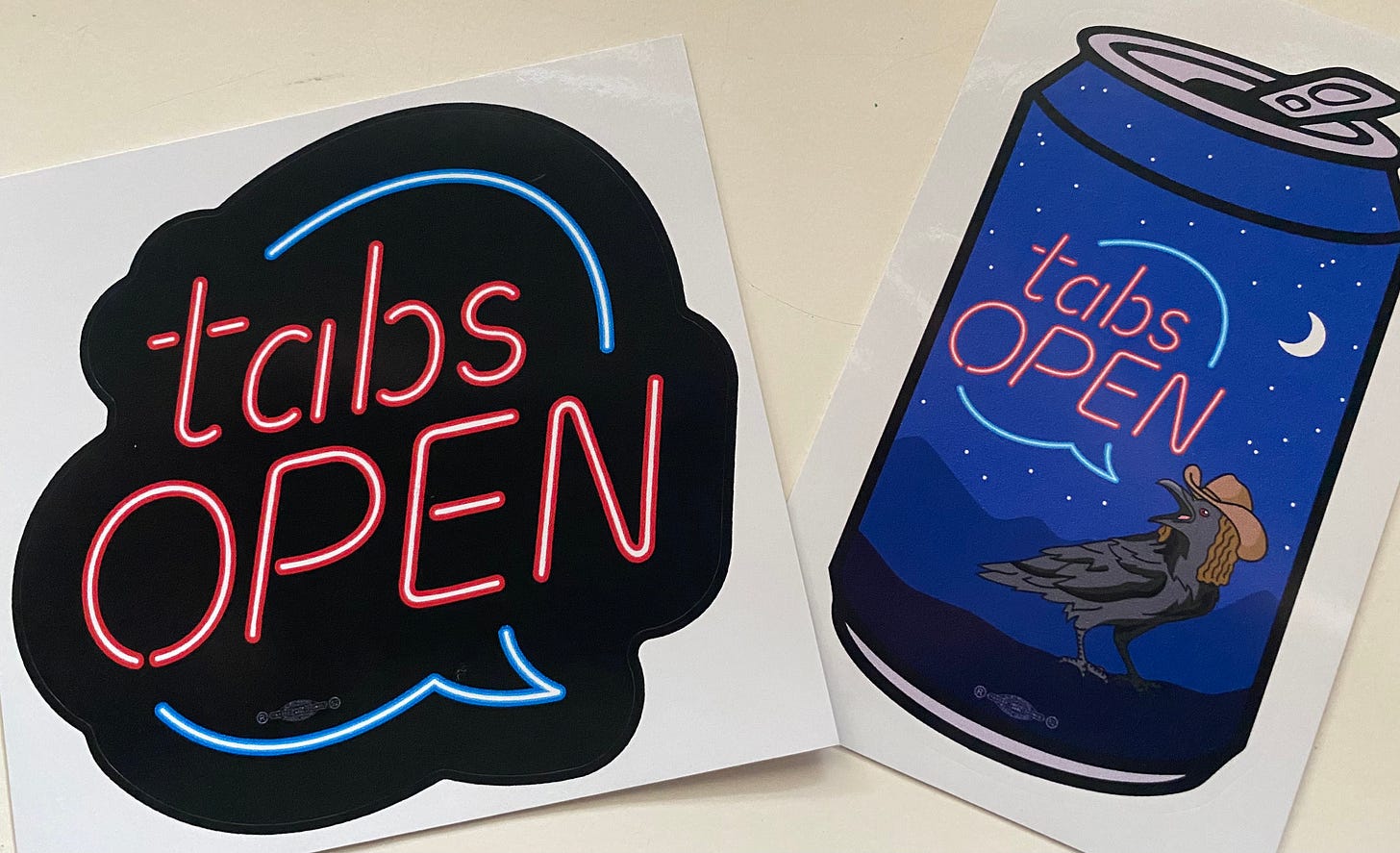

PS - To borrow a phrase, this newsletter is free, but not cheap. If you’d like to support Tabs Open, please consider buying a sticker or two (union made!). There are a handful of “neon sign” stickers left, and lots of “crow beer can” stickers left. You can also show your love by subscribing to get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week or by sharing this post with your networks.