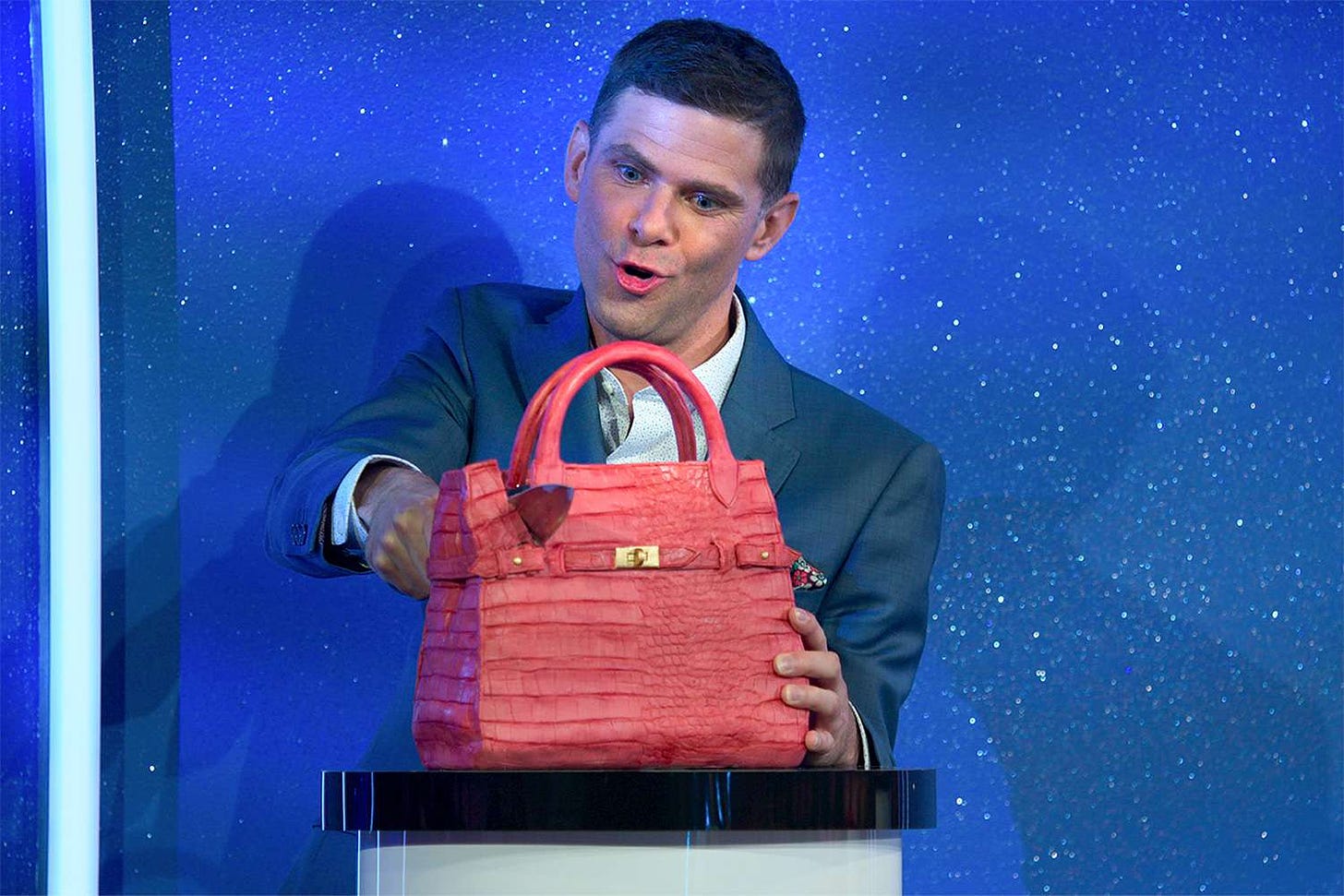

There’s a Netflix show called Is It Cake? that occasionally floats into my consciousness when clips appear on my social media feeds. The basic premise, as I understand it, is that bakers are set the task of reproducing various objects (purses, clocks, furniture, and the like) as cakes, with the goal of fooling a panel of celebrity judges into thinking their cake object is the “real” object.

It stretches the imagination of even a greedy little treat boy like me to imagine that these things actually taste particularly good, but that’s beside the point. People are clearly interested in watching artisans produce something that requires real experience and talent, even if that something is itself unreal, an imitation of something else.

James Porter opens his 1986 essay “Intertextuality and the Discourse Community” with the following summary:

At the conclusion of Eco's The Name of the Rose, the monk Adso of Melk returns to the burned abbey, where he finds in the ruins scraps of parchment, the only remnants from one of the great libraries in all Christendom. He spends a day collecting the charred fragments, hoping to discover some meaning in the scattered pieces of books. He assembles his own “lesser library . . . of fragments, quotations, unfinished sentences, amputated stumps of books” (500). To Adso, these random shards are “an immense acrostic that says and repeats nothing” (501). Yet they are significant to him as an attempt to order experience.

…We might see Adso as representing the writer, and his desperate activity at the burned abbey as a model for the writing process. The writer in this image is a collector of fragments, an archaeologist creating an order, building a framework, from remnants of the past. Insofar as the collected fragments help Adso recall other, lost texts, his experience affirms a principle he learned from his master, William of Baskerville: “Not infrequently books speak of books” (286).

Predating, as it does, any widespread use of the internet as a communication tool, Porter’s piece nevertheless speaks to a set of ideas that are still salient today. In my own classroom, I try to get my first year writing students to think of good writing (and other acts of creative production) in similar ways: not as lightning strikes from the minds of world-historic geniuses, but as the outputs of an entire ecosystem of people and their dialectical relationship with the material conditions of their world.1 Writing, in other words, is a communal act, even if you’re alone when you sit there sweating over the blank page.

James Berlin, in 1988’s “Rhetoric and Ideology in the Writing Class,” also takes this dialectical approach, saying that “[b]oth consciousness and…material conditions influence each other, and they are both imbricated in social relations defined and worked out through language.” We make our language and our language makes us, back and forth forever and ever, a sort of Escher staircase of engagement with the world.

You may have guessed where this is heading: these principles are exactly why I proudly do battle every semester with the AI tools that have been unleashed upon us all.

By leaning on something like ChatGPT, students are producing written content through their use of a tool that can’t understand or participate in material social relations, which means that it will never be able to “think” in the true sense of the word. But as the use of the tool becomes more normalized, it will inevitably help shape and define what thinking—what language itself—looks like for the user. And as more and more AI-generated texts enter the world, eventually the corpus of writing that the tool scrapes from to create its “texts” and assist the user will be indistinguishable from its own outputs, collapsing what people think of as writing into simulacrum. (These are the things that keep me up at night.)

This brings us back to Adso of Melk: the monk, at least, realizes that the scraps he is arranging into new order are only meaningful insofar as they were once arranged differently and more fully into texts that did have coherent meaning. In the case of AI tools, with the human interlocutors on the other side of the equation obscured and flattened, we have a similar problem: the generation of a text that appears full and coherent, aggregated from so pieces of writing that no original authors, nor their intentions, can ever be known. But unlike Adso, the “authors” here refuse to acknowledge the problem at the heart of their actions.

This does not mean I am against imitation—I think the premise of the cake show is interesting, and the people on there surely have artistic talent. Nor am I against the mechanical supplementing the human—consider the ice cream truck. The vendor is probably not himself a musician; the truck plays tinny and simplified versions of well-known tunes like “Pop Goes the Weasel” or “Oh Susanna.” These crude facsimiles of songs do not sound good, necessarily, but they are precious to us because of their role in a larger ecosystem of memory-making and identity formation. They still elicit a Pavlovian sort of response because of the context in which we know them: the endless summer days of childhood, bare feet on hot pavement, pleas for cash working on fake-irritated parents, the sensuous whiff of diesel fuel. Using AI tools to communicate through writing meets half the criteria here—the bare replication of a manner of human expression—but fails to meet the other half, the half where the context of memory, of sociality, imbues that expression with actual meaning.

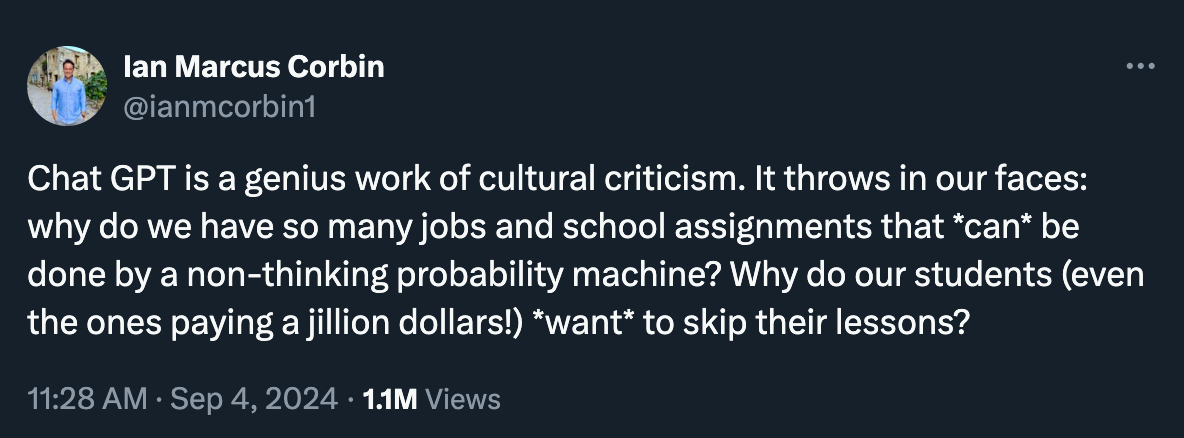

A recent tweet helped me clarify my own thinking in this regard:

By “clarify my own thinking,” to be honest, I meant “pissed me off a little bit.” But that’s okay: it’s good to get a little pissed off, especially if it leads to some clarity. It was Ian’s first question here that reminded me of the cake show; as someone who creates school assignments, I think they *can* be done by ChatGPT in the way that a sofa made out of cake on the cake show *is* a sofa.2 It appears to have all the right exterior components, but the filling is all wrong, assuming you actually want it to serve the purpose of the object it stands in for. I can’t tell you how many papers I waded through last semester that used the same lofty, thesaurized language to say absolutely nothing. How could they? They were several mechanized steps removed from any act of thinking, of language production, done by a human being in the context required for those things.

My friend Marianela wrote a piece last week in her excellent newsletter the immense wave about her own skepticism that the time-saving potential of AI can ever be worth the tradeoffs:

The employment of these models is deeply antisocial…because they cut off communication with and within the self. Their use foments an instrumentalist view of writing and even speaking, of language itself, foreclosing the possibility that we might use language as a means of discovery. When a LLM spits out a text based on a prompt, it makes something that looks like an essay or a poem but cannot be either of those things because it communicates not the true consciousness of its creator but merely her intent. Any writer knows that you rarely make the thing you intended to.

That leads me to Ian’s second question, which I find far more interesting. One answer is that students have always wanted to take shortcuts and skip their lessons because the alternative of doing no work and choosing freely how to spend one’s own time is always more desirable than the opposite path, even if the work is interesting. This is inevitable in a society in which education is often merely a training ground for employment, if not in subject matter than certainly in its preparation for systems of hierarchy, surveillance, time ownership, and punishment. The ready availability of ChatGPT would be less problematic and less tempting in an educational system that truly valued process as much as product, and shaped students’ thinking and behavior accordingly, but that is not the system we have.

Another is that most teachers, especially at the college level, simply aren’t all that invested in making the class interesting. In the eleven years between the end of my undergraduate education and the time I started grad school, I had forgotten that most college professors aren’t hired because they have any particular skill at teaching their subject, but because they are experts on their subject. So I’m not even blaming them for their classes being uninteresting, per se. If it’s not what they’re getting paid for and they have all kinds of pressures and incentives to spend their time doing otherwise, why would they do the work required to make that leap?

Whatever the case, individual educators like me who are experts in nothing but are invested in pedagogy sit far downstream of the policy decisions and socioeconomic currents that determine what kinds of tools and systems we will have to confront and contend with and even learn to use in our own classrooms. To the extent I have any hope that I won’t have to spend the rest of my teaching career donning my rusty armor and tilting at windmills, it is less that some great cultural backlash will destroy ChatGPT and its counterparts and more that the people at the top of this particular heap are such greedy morons that their investments in this sector will eventually fail.

Either way, I know what I want my classroom to be, and I know what I want my students to be. I know that my job is to teach them to bake cakes that taste good, and to make furniture that functions as furniture, and that if they want the one to be the other they better invest enough in their craft to learn to do it for themselves.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next time.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

Austin Kleon calls this kind of network a “scenius,” which I have borrowed for my own classroom use rather than trying to talk to teenagers about the dialectic. (If I stick around higher education long enough to become an old crank, though, I make no promises.)

And in the latter case, at least a person still made it on purpose!

Top-flight transition from Is It Cake to Umberto Eco here 👌

Thoughtful and provocative as usual, Chuck. And Marianela's quote is so true -- "Any writer knows that you rarely make the thing you intended to." The "cheat" of ChatGPT is the cheating of oneself (not the beleaguered instructor), of the joy of discovery, of the process of thinking and creating while writing. Those sneaky Eureka moments! There's also the old-fashioned satisfaction of a hard job well done. I recall a former English prof of mine smiling when he said, "I don't enjoy writing -- I enjoy having written." I'll take that.