Even The Solid Ground Beneath You Begins To Move

We were not attuned to the beauty of an order which we did not impose

There’s a bit from Jim Harrison’s novella The Farmer’s Daughter that has stuck with me for a few years. It reads:

She wept briefly then figured weeping wouldn’t help one little bit. She thought of the damage people do to each other, sometimes incalculable, and then there was the damage you could do to yourself by toughening up.

Completely unrelatedly you may have noticed that the country appears to have shrugged its collective shoulders this past week and started reopening against all reason and conscience.

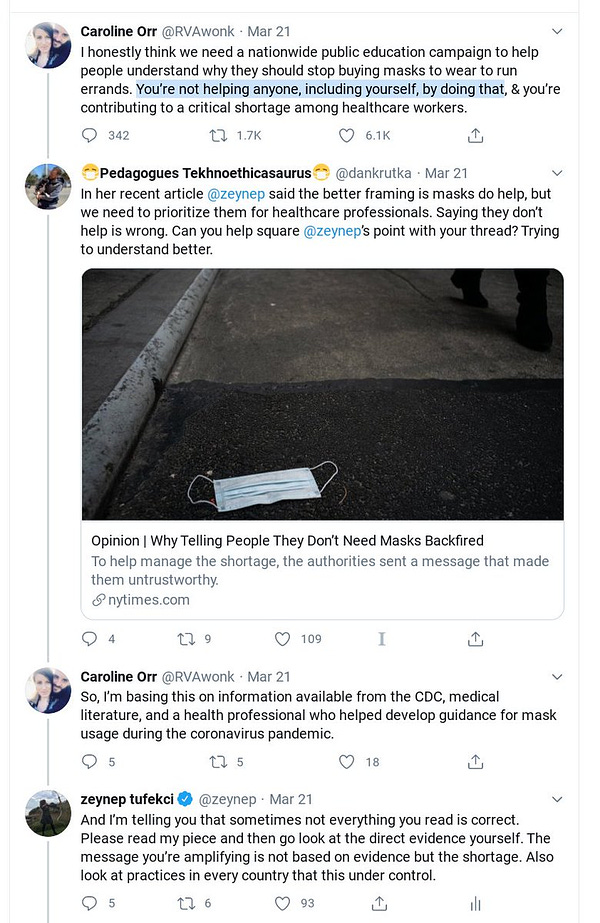

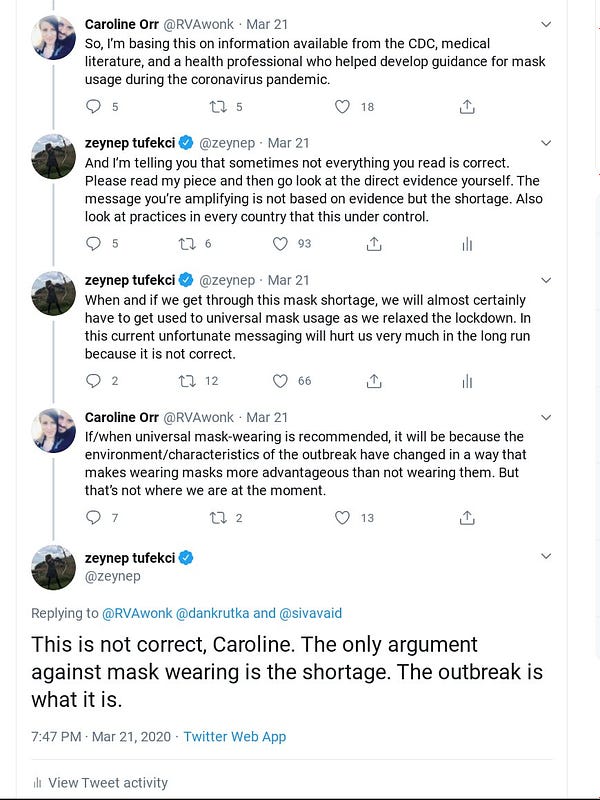

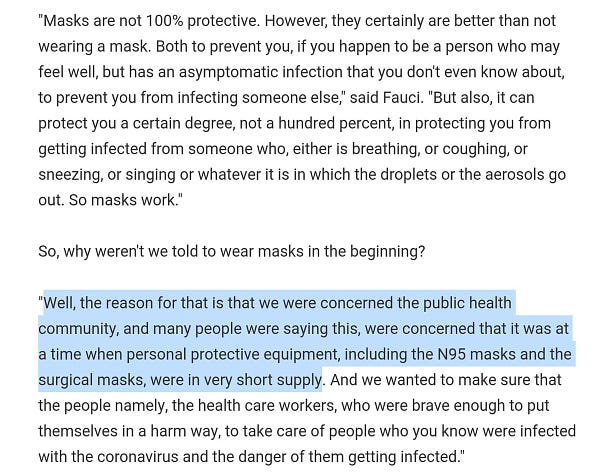

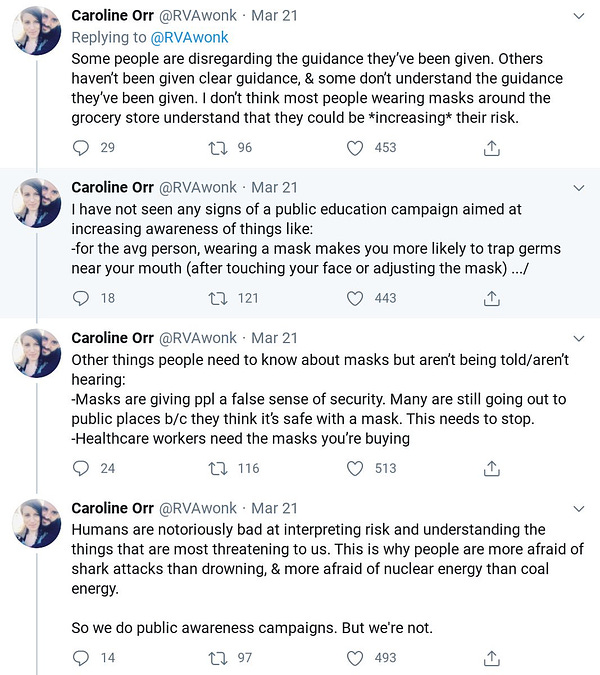

It is easy—and understandable, make no mistake—to get upset when you walk past a full bar or restaurant where no one is wearing a mask; that others would be so cavalier about this is something that I struggle to wrap my head around daily. But I also have to remind myself that there is no strategy. No one is in charge and no one is directing the operation. And what institutions do nominally exist for taking over at a time like this, like the WHO and CDC, are still in thrall to the same systems crushing everyone else. There’s reason to believe that those first few weeks of wildly inconsistent information about whether or not you should even be wearing a mask were almost certainly not a product of incompetence, but of a conscious decision-making process designed to prevent a “supply problem.”

What do you do with that? What do you do with information that, if you look at it head-on, seems tailor-made to make you feel insane and hopeless? In that vacuum of leadership and authority, people are going to do reflexively what feels most natural to them. Very few of us are immune (ha) to that. I know that in recent weeks I have been loosening up the rigid structures that defined my life for the first few months of this quarantine, empowered by the knowledge that in Washington state we were doing one of the best jobs in America of isolating and flattening the curve. But even that may not matter, as the national case rate continues to climb and states continue reopening as though any progress has been made.

But one of my deepest fears surrounding the mask issue is that it will even further destroy any notion of solidarity, of a collective national interest. If I take my own gut reaction to seeing a college friend posting Instagram stories from a crowded bar and multiply it outward to the rest of the population—how many people are becoming irrevocably steered toward the belief that their neighbors who seem less socially conscious or intelligent than themselves are, in fact, the enemy? The idea that all of us, the conscientious and the reckless, the “reopen Denny’s” protesters and the Black Lives Matter protesters, might have something in common—namely, that we are all under the heel of the people and institutions that control this country, and therefore all must work toward our collective liberation—is almost entirely absent from the American imagination. Of course I also believe that we all owe each other something, too, but you can’t shame people into believing in the common good. You have to model it yourself, which is no easy thing.

An interesting (or maybe horrifying) corollary to this is the data we have about what happens when people read about the concept of white privilege. Per one study published by the American Psychological Association,

while social liberals were overall more sympathetic to poor people than social conservatives, reading about White privilege decreased their sympathy for a poor White (vs. Black) person. Moreover, these shifts in sympathy were associated with greater punishment/blame and fewer external attributions for a poor White person’s plight. We conclude that, among social liberals, White privilege lessons may increase beliefs that poor White people have failed to take advantage of their racial privilege—leading to negative social evaluations.

What a grim result to contemplate, and perhaps an unsurprising one, given that liberal discourse has expanded the term “privilege”—which connotes something extra, something unearned, not to be expected by all—to encompass even very basic human rights like “not being murdered.” The last sentence of that abstract was particularly clarifying: that white liberals are either so convinced of their own superiority or so unable to engage in any meaningful structural critique that they dismantle any possibility for solidarity even with other white people. (Which to me also suggests that “white” is perhaps a classification with less explanatory power than we typically ascribe to it, but that’s a discussion for another time.)

If we’re going to make it out of this with anything resembling hope, we have to start doing some thinking about the rigid ideological frameworks we operate in and the gut reactions we have to the events occurring around us. Because America is propped up by the myth of the supremacy of the Individual, it can only champion individual successes and it can only conceive of individual failures. I call myself a Marxist because I have found its explanations for what happens in the world far more compelling than what liberalism had to offer. This week’s Supreme Court decisions encapsulate that distinction perfectly: people celebrating Ruth Bader Ginsberg for helping lead the majority opinion on the landmark case affirming workplace protections for LGBT employees were aghast an hour later when she again ruled with the majority, 7-2, to allow the construction of a gas pipeline beneath the Appalachian Trail to continue.

In an effort not to be a hypocrite I will assert that I don’t blame those individuals who experienced whiplash from the apparent contradiction here. I think it’s a collective failure, a cultural failure, an educational failure. Social liberalism, being fundamentally an individualist political framework, is limited to a constant sorting of politicians and celebrities into Good and Bad, those we Stan and those we Cancel. (But Chuck, you may ask, how can you say liberalism is all about the individual when liberals across the country are trying to Do The Work, trying to be less personally problematic, trying to improve themsel—ah. Nevertheless.)

So I find myself compelled to ask: Do you want to sit around forever waiting to find out if the individual people who seem to have more power than God did the right thing one time, or are you willing to expand your imagination to believe in building a force capable of taking the fight to them? Think about the landmark employment discrimination case we just witnessed. The thing is, employers can’t specifically fire you for who you are within those categories now, but most of them were already savvy enough not to. As long as at-will employment is the law of the land, they’ll still fire you for being trans, they’ll just say they’re doing it because you were two minutes late to a shift three months ago. There is no way to fight that in an individualist framework, and no amount of allyship can repair that.

This Adam Curtis interview from 2017 speaks to some of what I mean by all of this:

You ask what real change might look like, and I think that’s a really interesting question for liberals and radicals, because there is a hunger for change, out there - millions of people who feel sort of insecure, uncertain about the future who DO want something to change. I think that change only comes though a big imaginative idea. A sort of picture of another kind of future which connects with that fearfulness in the back of people’s minds. And offers them a release from it. That's the key thing. But I think the question for liberals and radicals is - they are always suspicious of big ideas. That's what lurks underneath the liberal mindset. And the reason is - and they are quite right in a way - is look what happened last time when millions of people got swept up in a big idea! Look up the last hundred years - what happened in Russia, and then in Germany. The point is that political change is frightening. It's scary - it's thrilling because it is dynamic and is doing something to change the world but it is scary because it can change things in ways where nothing to secure. It’s like being in an earthquake. Even the solid ground beneath you begins to move. And things dissolve that you think are solid and real. And I think the question liberals are left have to face at the moment is a really sort of difficult question which is: “Do you really want change? Do you really want it?” Because if you do many of them might find themselves in a very uncertain world where they might lose all sorts of things. What we were talking about, in many cases, is people who are at the center of society at the moment, they are not out in the margins. They would have a lot to lose from real political change because it really would change things in the structure of power.

Or - and this is the brutal question: Do you just want things to change a little bit? Do you just want the banks to be a little bit nicer, or for people to be a little more respectful of each other's identities - all of which is good - but basically you carry on living in a nice world where you tinker with it.

That’s the key question. But you can't just sit there forever worrying about big ideas because there are millions of people out there who do you want Change. And the key thing is: they feel they’ve got nothing to lose. You might have lots to lose, but they feel they’ve got absolute nothing to lose. But at the moment they're being led by the Right. So things won't remain the same. But society may go off in ways you really don’t want.

Clearly, there is work to be done—work of emotion and imagination. A nation of millions reckoning, maybe for the first time, with that essential question: what am I willing to give up so that all might be free?

My friend Scott over at the excellent Action Cookbook newsletter touched on this theme a few weeks ago, as he watched history unfolding in Louisville (emphasis mine):

As Americans, we have long been educated to believe that we are forever moving toward the future. We have been taught that the past has blemishes but that the past has nothing to do with who we are now. History was simply something that led up to us; we are the triumphant end result of all those centuries people not getting it right. It’s this belief that has left many of us unprepared for a moment like this. It’s this belief that rings out any time someone aghast at the things we are seeing today claims “this is not America” or “we are better than this”.

…If justice is found for the people who have been lost this year, the fight for justice will not be over. If the economy rebounds, the fight to make it safer and fairer will go on. If we survive this pandemic, the need to care for our community’s health will still be as critical as ever. There will always be pretenders to a throne. We can no longer pretend that our problems are unique, that our problems are not shared, that the things that ail our society are not on each and every one of us.

I think we probably also need to have a conversation about what we actually mean by freedom. That great Individualist specter rears its head every time the conversation comes around to freedom, because a lot of people want it to mean “I do whatever I want and demand that the freedoms of others be restricted, if necessary, so as not to inconvenience me,” and the response to that is always the sort of limp and unconvincing “actually, your freedoms end where my rights begin.” Our American idea of freedom, which is really a negative sort of freedom—“No one can tell me what to do, I can’t be stopped”—is inadequate, to say the least.

Someone who I do find worth reading on this idea is Martin Hagglund, who was interviewed in Jacobin last year prior to the release of his excellent book This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom.

…unlike other animal species that we know of, we can treat that extra time as free time and ask ourselves what we ought to do with it. What is worth doing?

This is the basic motivation behind Marx’s critique of capitalism and his call for a different form of social life. To lead a free life, it’s not enough that we have formal rights to freedom. We must also have access to the material resources and the forms of education that allow us to own and engage the question of what we ought to do with our time together. What really is our own is not property or goods, it’s the time of our lives.

To be free also does not mean to be free from all limitations or constraints. To be free is to be able to devote ourselves to something we identify with and care about. So that might mean working really hard, but working in a way where we can see the point and the purpose and the meaning of what we’re doing. This is opposed to what Marx calls alienated labor, where our labor is not an expression of what we’re committed to, we’re just doing it as a means to an end, in order to survive.

In Hagglund’s assertion about what we must have access to in order to own our time and be more truly free, there is the hidden hard truth that, since we don’t have that yet, we’re going to have to work awfully hard to get there. Many of us will not live to see the fruits of that labor. We have to do that work anyway.

A tidy pairing for that Hagglund quote comes from L.M. Sacasas’ “The Convivial Society,” which included this rumination a few months ago on where that work might start.

Birdsong is ordinary and it is common. It arises out of an order I cannot create and I cannot own it. If my neighbor comes out to her porch, she too will hear it, and her enjoyment will not diminish mine nor will my enjoyment diminish hers. And, what’s more, should we both be here listening to the birdsong, we would now have something in common, something neither of us possessed and yet which by becoming a common object of our attention would form a bond between us, even if only for a moment.

These ordinary and common goods tend to be mine neither to create nor to possess. They are, interestingly, only mine to enjoy or to destroy.

And I find, too, that there is greater joy in ordinary things commonly pursued than extraordinary things privately consumed.

This time, for many of us, is a time during which we find ourselves rediscovering both the ordinary and the common, perhaps realizing that we’d discounted their worth for far too long. We were not attuned to the beauty of an order which we did not impose. We were unable to value the goods on which we could put no price or which we could not claim for ourselves.

Part of that work is in finding our common humanity so that we might build solidarity, rather than a hollow and altruistic notion of “allyship.” Not to keep pumping his tires but Scott from Action Cookbook once again included something in his newsletter that I think illustrates the point well, a reflection from Thomas Merton:

To be “thought of” kindly by many and to “think of” them kindly is only a diluted benevolence, a collective illusion of friendship. Its function is not the sharing of love but complicity in a mutual reassurance that is based on nothing. Instead of cultivating this diffuse aura of benevolence, you should enter with trepidation into the deep and genuine concern for those few persons God has committed to your care—your family, your students, your employees, your parishioners. This concern is an involvement, a distraction, and it is vitally urgent. You are not allowed to evade it even though it may often disturb your “peace of mind”. It is good and right that your peace should be thus disturbed, that you should suffer and bear the small burden of these cares cannot usually be told to anyone. There is no special glory in this; it is only duty. But in the long run it brings with it the best of all gifts: it gives life.

My one quibble with Merton here is the framing that still posits a power dynamic—you employ people, you teach people, you are the head of a family. The lesson should be the same even if you are in no such position. The responsibility is the same. Or, as Jim Harrison put it in The Games of Night, another novella in his The Farmer’s Daughter collection:

There’s no guarantees but if you don’t love you’re a coward.

Thanks as always for reading. Read something about Juneteenth today, and start to plan accordingly. Talk to you next week.

-Chuck