One of the nice things about being a teacher is the ability to go off at some length about things that are important to you. Ideally you’re not holding an audience of students hostage, obviously, and your rants hopefully relate in some way to the course material at hand. But having the power of this prerogative is occasionally very exciting.

The Language Arts and Social Studies theme in my GED class this quarter is “Radicals and Revolutions,” which for someone with my predilections is awfully fertile ground for the occasional tangent. And while our Science content for the quarter is themeless, really a general survey of topics that are required for passing the GED…well, I make the curriculum for that, too.

Before we discuss the people and movements who made history rebelling against injustice, I ask my students to think—for days on end—about how the contexts in which these forces emerged were formed.

We look at a heat map of the most populous cities in America, and we ponder how they came to be so populous. Not settling for a tautology, lots of people live there now because lots of people were already living there, but taking serious stock of the material conditions that move the world forward. We look at that one until someone arrives at the word water as the common thread uniting these places. (We also talk about Phoenix, Arizona, which cracks the top-ten population list despite being an artificial Mars-scape where no one has any business living.)

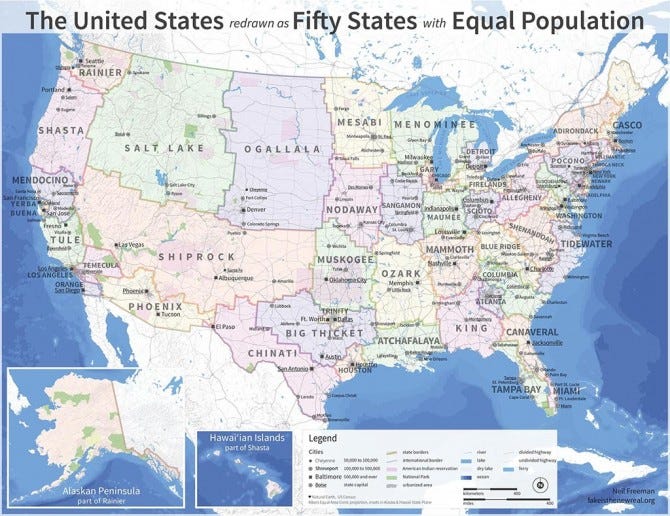

We look at another map, of a redrawn America where the lines create fifty states of equal populations. We think about why it is that the country isn’t drawn that way and instead is so squiggly and irregular until someone arrives at the word water again, and realizes that back in the day it was harder to cross a river. So much harder that oftentimes they just said to hell with it, everything on that side is something different from what we are over here.

My students tolerate this for the most part and my heart grows a few sizes at the times when I can watch their understanding start to deepen right in front of me. I think if you’ve never taught before you might overestimate the frequency with which teachers get those Dead Poets Society moments, and even when those connections do happen they rarely look like a masterful orator holding a rapt class in thrall.

What they do look like varies. And everyone having masks on makes it difficult to see comprehension dawning on anyone’s face. But sometimes you spend three class days working toward explaining a concept and then you throw another map up on the screen and without prompting, someone says something so astute that you want to cry or pump your fist or praise them so effusively that they’re too embarrassed to ever come back to class.

The other day, to close a lesson, I put up a map of the Mississippi River watershed. It was a last minute addition, something I had found by chance on Twitter, where I learned that this one system covers a whopping 41 percent of America’s lower 48, but all pours out into the Gulf of Mexico through one comparatively narrow channel in Louisiana.

“That must be why it floods so much there,” one student called out.

“Maybe this is why it’s so important we fight to stop oil pipelines on indigenous land,” said another. “If that’s all connected like that, one burst pipeline could mess stuff up for millions of people.”1

I hadn’t even asked any questions, just posted the map and told them what it was. And in seconds there was this lightning chain of ideas going around the room.

Water and connections. When I pop off about science in the classroom, it’s often along these same lines. In our recent discussion about ecosystems, students had to respond to the question: “In the same ecosystem, would the limiting factors for a bear be the same as those for a tree? Why or why not?”I expected the answers to be along the lines of “yeah, sort of — bears and trees both need food, water, and living space, but have different needs within those categories.” I got some of that, but I also got something I didn’t know I was looking for, which was a set of further thoughtful questions and ideas.

“I just Googled it and an adult grizzly bear can occupy up to 600 square miles of territory. So there’s some overlap but overall, not really, no, because a tree doesn’t need anything like that.”

Or:

“In the Arctic there aren’t any trees, but there are plenty of polar bears, so I’m gonna say no too.”

Or:

“I don’t know much about trees. I don’t know if they have to fight each other off for resources like bears do. I guess they probably do. So…yes? Do they?”

If you’ve ever seen one of those memes where someone’s eyes start shooting lasers you’ll have some idea of how I felt the second I heard that.

What I told them, and what I’ll tell you, in case you didn’t know, is that for the most part—particularly within large forests—trees do not compete in any sense we would recognize. What they do instead is cooperate, although even that feels too soft a term for what is really more like the internal machinations of a single massive living thing. Teeming with parts and complications, but all aimed toward the same purpose: not just to live, but to live everywhere, to thrive in messy complexity in a cycle of birth and life and death and rebirth. Trees communicate chemically to warn each other of attacks by bugs or defoliating animals. They redistribute their resources across their networks to make sure more trees can thrive. Trees are good neighbors, in other words.

As Richard Powers writes in The Overstory:

When the lateral roots of two Douglas-firs run into each other underground, they fuse. Through those self-grafted knots, the two trees join their vascular systems together and become one. Networked together underground by countless thousands of miles of living fungal threads, her trees feed and heal each other, keep their young and sick alive, pool their resources and metabolites into community chests…There are no individuals. There aren’t even separate species. Everything in the forest is the forest. Competition is not separable from endless flavors of cooperation. Trees fight no more than do the leaves on a single tree. It seems most of nature isn’t red in tooth and claw, after all. For one, those species at the base of the living pyramid have neither teeth nor talons. But if trees share their storehouses, then every drop of red must float on a sea of green.

Through mycorrhizal networks, which splice underground arrays of tree roots together with fungal threads, the whole forest talks to itself, and shares itself with itself. It’s the kind of living miracle that makes me emotional if I think about it for too long. (Clearly that comes through aloud, too. The student who had asked the question let me finish my rant and then said, kindly, “I’ve never heard anyone care so much about trees before.”

It’s my sincere hope that you have places in your life where you can share the things you’re passionate about with people who will listen. And I think a big part of cultivating that is doing some listening of your own, and remaining open to the possibility of being surprised, even in situations where you are ostensibly the expert.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be.

I know the “woke, precocious child allegedly expressing note-perfect progressive political ideas” phenomenon is a real plague online, but this is as close a reconstruction of these comments as I was able to get down right after class. And my students are all teenagers and young adults, many of whom are plenty radical without any of my help. In case you were suspicious.