When I was eleven or twelve years old1 my mom’s family took a road trip from upstate New York, where we all lived, to the little town of Canaan, Maine.

Besides its actual purpose, I remember a lot of minutiae about that trip: my most serious aunt having such a good time that she attempted to throw one of the whiteboard markers that we were using to communicate between vans (no one had cell phones yet) from one vehicle to another, on the highway. Eating chocolate chip pancakes for breakfast every morning in a diner called The Purple Cow. The full head of bleach-blonde hair I was sporting that year. Multiple cousins melting down as we attempted to record a karaoke video of Three Doors Down’s “Superman” in some sort of weird children’s science center. Spelling out “HELP” and “SOS” in wax-coated Wikki Stix on the van windows until my mom noticed and made us scrape them off. A lot of entertainment in those days was based on trying to communicate out of the back windows of moving cars, I’m realizing.

The reason we were actually making the trip was that we were visiting the Lindbergh Crate Museum, a since-relocated monument to Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight housed entirely in the actual wooden box his plane was shipped home in. Why was quirky attraction this worth an interstate trip for our entire network of aunts and cousins, you ask. Well, the guy in charge of the navy ship that brought the pilot, the plane, and the crate back across the Atlantic—the leg of the journey no one ever really thinks about—was family.

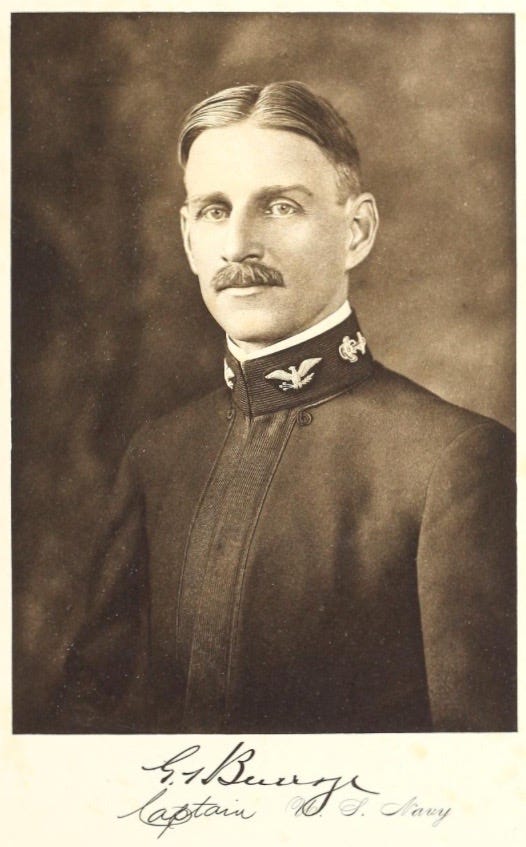

Vice Admiral Guy Hamilton Burrage was my maternal grandmother’s grandfather. (Making him, I guess, my great-great-grandfather. We need to get some of our people on developing less clumsy terms for those ancestral relations.) Besides his bringing back Lindbergh, he commanded the U.S.S. Nebraska during World War I and received the Navy Cross for “meritorious service in the line of duty.” He maintained a friendship with Lindbergh in the years after their trip together and was even briefly involved in the hunt to recover Lindbergh’s baby after his kidnapping. Beyond that, information about him online is somewhat scant. (The William & Mary Special Collections Center does have an archive of G.H. Burrage materials, my favorite item of which is labeled “Photographs of drawings of various tall-masted ships, undated.”)

When we visited Canaan, we were greeted as honored guests by the man who had founded the Lindbergh Crate Museum, Larry Ross. Larry was one of those old-school Mainers you read about in the periphery of Stephen King or Tess Gerritsen novels: hardy, decked out in flannels, with a warm crinkle around the eyes. His accent might have summoned lobsters out of the ocean. (“Now, yah great-great-grandfawtah…”)

Larry is who this story is really about. Not the famous and morally questionable aviator, nor the decorated Navy man who brought him home. But a gentle, humble guy living in a woodsy town who pursued a single-minded passion to its healthiest possible end.

Larry treated us with reverence, even the kids among us. Like true heirs to the stories and materials he had lovingly and doggedly tracked down over the course of more than a decade. That kind of dedication awes me, when I think about it for long enough to do it justice.

“I used it as an educational tool to work with kids and I used Lindbergh’s flight as an example of having a vision of what you might want to achieve in your life,” Ross said. “I would try to introduce the kids to people who I thought were interesting role models.”

When Ross saw the advertisement for the crate’s sale, it instantly resonated with him and his love for history.

“I’ve always loved U.S. history as a kid and we would travel every summer from Massachusetts, where I’m from, to Colorado, where my mother was from,” Ross said. “My parents would let me sit in the back of the car with a map and everyday I could pick out one place that I wanted to go and visit. So when I read that story I just thought, ‘This is exactly the kinda place I would’ve wanted to go as a kid’… so I went to check it out and I just thought, ‘Here is this part of history, this is my chance I can make this happen and I can use it to tell a story.'”

Larry bought the crate for $3,000 in 1990. It had lived a full life of its own by then. Not mentioned in the few news stories covering the crate’s path from the naval ship that carried it to Larry’s backyard: its occupation by my great-uncle Harry, a Green Beret during Vietnam, who lived in the crate when he returned from war, turning—like so many others—to drugs to cope with the physical and psychological wounds he’d received overseas.

By the time any of us saw it, it had been lovingly restored—a far cry from the “shack” it was described as in a newspaper item about the purchase. Larry even added porches, doors, and windows.

I have lately been trying to imagine what kind of mind it takes to pursue a single task so doggedly. Larry, in an interview with Roadside America, provided some insight:

Ross's personal mantra is, "Hang your own carrot," taught to him by his mother. "You have to be able to motivate yourself," he explains.

I’m not sure I really understand that, but maybe I don’t need to. I got to experience the magic that was Larry’s dedication—not just to a project of his own obsession, but to one he thought could make other people dream bigger and aim higher themselves.

None of us kids spent much time inside the crate. At that age dusty photos and newspaper clippings don’t hold much interest. But we did, as you can see at the top of this issue, get to find inspiration another way. Larry had built a small “plane” on a zipline, dubbed Spirit of Canaan in an homage to Lindbergh’s own aircraft. And for one afternoon, in a kindly stranger’s backyard, we flew.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

I was checking in with my mom about when this trip took place and we knew it had to be around 2001 or 2002, due to my dyed hair and “because your brother was still small enough for you to put him in the motel room fridge,” an incident regarding which I will plead the Fifth.