I Am A Wild Beast

Teaching and learning are the most ancient rites we have

The start of a new semester brings with it all sorts of feelings. I’m in my twelfth year of teaching in one role or another, and while I am certainly more confident and competent than I was at the beginning of my career, the jitters heading into that first week have never gone away.

With those jitters, I’ve found, comes a sort of meta-reflection on teaching itself as a practice. And as I have recently become obsessed with notions of deep time, of prehistory, this year that reflection has led me to think about how teaching is just about the most ancient practice we have as humans. Most sentient species do this in some way, obviously, but if anything that makes it even more touching to be able to participate in such an ancient ritual, one that connects us to so many other living things. Eat this mushroom, but not that one. Walk this way on the ice to keep from breaking through. Care for the injured. Warmth is survival. Don’t rely on internet citation generators to create a works cited page.

Alright, maybe that last one is a little less moving and timeless than the others. But it belongs to the same ideological lineage: that teaching does not exist in a vacuum, does not exist without its corollary, which is learning. It’s a relationship that requires a kind of bi-directional trust that the other party is hearing you or being heard, and that what is being said has value—to the person, to the community, to the society of living things. Proper MLA formatting on an argumentative essay may not have the same existential applications as which mushrooms you can eat or how to build a fire—though I would happily teach my students what I know of those things if there were room in the curriculum—but to me it fits neatly into a chain of human relationships that we have been a part of for our entire existence, that chain of education that is at the core of who we are as a species.

In this vein, I think constantly1 of Onfim.

Onfim was a little boy, aged six or seven, in medieval Novgorod, Russia. (The year 1260 is hardly prehistoric, but bear with me.) We know little about him generally—whether he lived to adulthood, what he did with the rest of his life, whether he married, whether he was a good man—but we do know of him. We know this because some of Onfim’s schoolwork survived. Or more accurately, some of what Onfim was doing in the margins of his schoolwork survived.

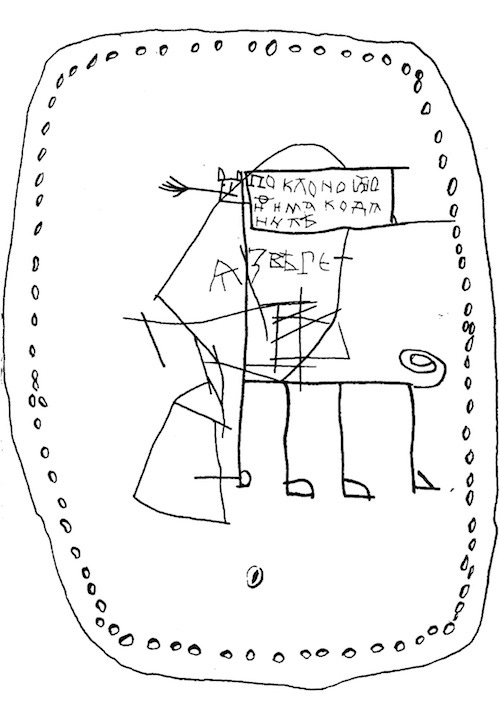

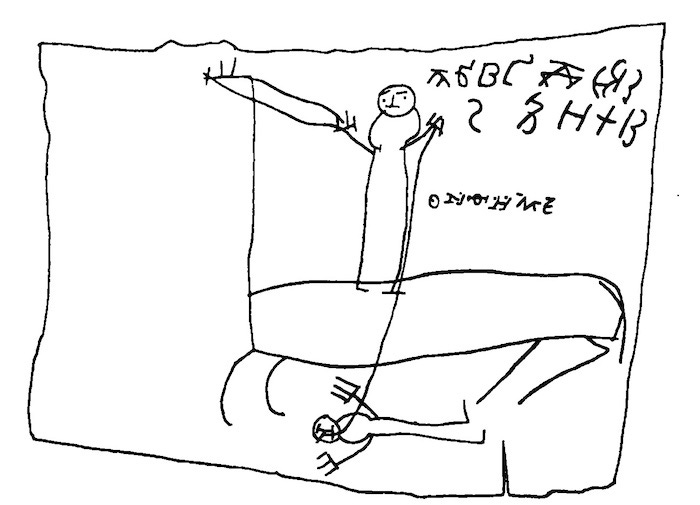

On paper made from birch bark, Onfim did spelling exercises, copied passages from Psalms, and most importantly, drew various scenes of battles, monsters, and knights, many of which involved himself. He even drew and labeled another kid, presumably a friend and classmate, Danilo. We know even less about Danilo than we do Onfim, but he has been immortalized on the birch scrolls all the same.

It is of course adorable that it seems like kids have just always been like this, that in these scenes and drawings, and the preceding impulse that created them, we see ourselves, our own childhoods, even though they were produced in a time, land, and context so foreign to our own. But Onfim’s doodles, especially because they were made in the context of his schooling, tug at me for other reasons, which I think Justine E.H. Smith puts quite nicely:

The fact that [drawings] endure from ancient Mesopotamia to the present day does not license us to assimilate them, but rather opens up the possibility of perceiving depth, antiquity, and perennity in what we can ordinarily only grasp as our trivial and fleeting everyday life. It is not that the loves and losses of the ancients are merely like our trivial frustrations in online dating, but that these very trivial frustrations are inscribed within the long golden chain of human experience, and it is only art and literature that can reveal the length of that chain to us. It is not that ancient images of dragons and battle are merely like our refrigerator doodles, but that our doodles, or our children’s, inscribe us into the life of the imagination, whose recording in material traces it is the business of art and literature to continue.

Onfim may be a distant ancestor to us, a link in the chain we can reach back into the past and call out to, but the fact that he used writing at all to express himself means that link is very near our own. Written language has been around for 5,500 years or so; the human species for 190,000 or more. That means ninety-seven percent of human history wasn’t put down in words. But we do have pictures, so many pictures: works of art carved into stone, painted on cave walls, pounded into the earth.

Consider Chauvet Cave, one of the best-preserved sites of prehistoric cave paintings. It was occupied and used ritually at two distinct points in the history of what is now France: one from roughly 37,000 to 33,500 years ago, the next from roughly 31,000 to 28,500 years ago. So many people can’t even see other people walking the earth today as fully human; imagine what little connection they must feel to those who were born eighteen times further back in history than Jesus Christ. (These two different societies themselves had a greater temporal distance between them than the entire existence of Christendom. And still we flatter ourselves that this is the most important era in human history.) The mind reels. And yet it is the knowledge that these people did exist, that further back in time than my puny brain can comprehend in any meaningful way there were human beings moving through the world trying (and succeeding!) to make sense of their surroundings, that makes me feel more human than anything else. The same blood runs in my veins, and yours. Our biological needs, our impulses toward care and community, our body structures are the same, albeit warped and attenuated by the industrial capitalist age into which we were born.2

The paintings on the walls of Chauvet Cave were not simply expressions of artistic whimsy, as far as we know. It is likely that they served ritualistic and shamanistic purposes, perhaps for protection from, or transformation into, the animals they depict. At this we can only truly guess; it seems farcical to purport to “know” anything about the interiority of people as complex as us in a context that has not existed since at least the last Ice Age. Whether the shaman theory is true, or some other ungraspable reality is true, the drawings in Chauvet Cave and elsewhere, given their sophistication and animation, required teaching, required learning. The process of recreating, in charcoal, cave bears and cave hyenas, aurochs and mammoths, rhinos and lions required practice and refinement. The passing on of knowledge, the assessment of one’s creations against a standard set by others. We have been teachers and learners for as long as we have been people.

This is not to say that I think of myself as a shaman, imparting some wisdom to my otherwise empty-headed pupils that I myself gained from a mystic journey within the recesses of a cave. Quite the opposite. I believe education is a dialectical process, one in which both teacher and student are learning as part of a relationship that is constantly being refined and reconditioned. A cliché you hear from educators sometimes is that “I learn more from them than they do from me!”, and while that probably sounds annoying to people who aren’t teachers, I sincerely believe that it’s true. In fact it’s the only thing that can be true, unless a teacher is so invested in running their classroom like an army regiment that they foreclose on the possibility of change. I am constantly learning from my students, and when I say that I don’t really mean that I’m learning trivia from them that I didn’t previously know (which is probably what people hear in that statement, and even this is true sometimes), but that being in community with them forces me to constantly reassess my own priorities, attitudes, and understanding of the world. Each new class of students I teach has unique experiences and perspectives, and so each class will also have unique needs, needs that it is my job to meet.

How could it be otherwise? How could I wish it to be otherwise? It is a joy to participate in such a process, one that has the power to connect me to everyone who has ever lived.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next time.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

I will not say this is my Roman Empire. I won’t do it.

Modern medicine: huge for us. Microplastics, lead, processed sugar: big old swing and a miss.

It is an honor to add my textbook doodles to the long sacred chain of human heritage.