I Form A Silent Contract With Whoever's Name Is On The Papers

How the hell can a person go to work in the morning, come home in the evening, and have nothing to say?

The dirty secret that animates this newsletter is that most weeks I have no idea what the hell I’m going to write about until I’m pushing right up on the completely arbitrary late Wednesday deadline I’ve set for myself. As the days after publishing the last issue tick past I am thrust almost immediately back into the cycle of trying desperately to find more source material and more ideas of my own that I haven’t completely exhausted in this space already.

Really, things work out best when I stop forcing it and just start passively absorbing material, reading things I think look interesting and mindlessly scrolling social media. One rich vein, somewhat embarrassingly, is Tumblr, where I still operate the skeleton of an account. (Tumblr’s rap is at least half-deserved but I have also made at least a half-dozen actual friends on there, so it’s been a net positive.) Anyway the other day I came across a post talking about the dangerous trend of people trying to 3D print medical supplies and equipment at home—an understandable phenomenon, if a misguided one. The relevant pieces are below.

The very last bit is the one I find myself still thinking about a few days later—the notion that the built environment we operate in requires a massive amount of trust, at a level that’s hard to think too concretely (ha) about lest one become existentially terrified. One of my best friends is a structural engineer; the level of care and attention he puts into the minutiae of every single project is astonishing. And I am basically a babe in the woods, bumbling around trusting that every single person who has his job (and dozens of other jobs) is as skillful and attentive as they design the world that all of us are part of.

These past few weeks have been a lesson in what happens when that trust starts to break down. How fragile are our supply chains, our bureaucracies, our transportation systems! How important are the people who most people never think about; how inessential are so many other jobs that we have convinced ourselves that people must do.

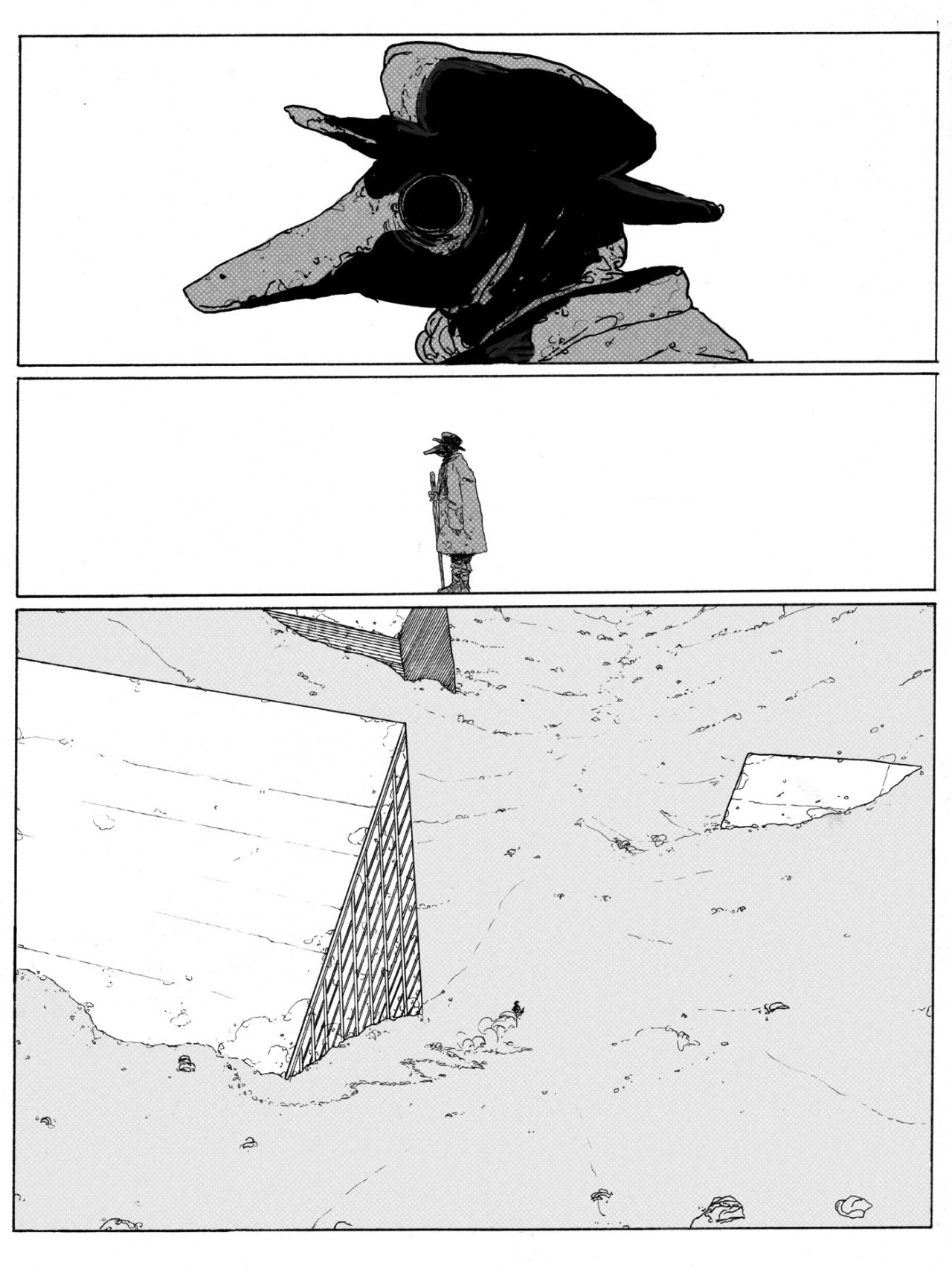

That’s a panel from Liam Cobb’s “Death of a Crow”, another good Tumblr discovery that I find again every few years and sit in quiet awe of. In Cobb’s vision of the future the built world has survived, or at least the tallest bits of it. The structural engineers have done their jobs well, but the rest of the people tasked with maintaining the living world have not.

Luckily we don’t live in that world yet. Not entirely, at any rate. And I take heart knowing that some people are thinking through how best to construct things, during this crisis and beyond. Because we should not make the mistake of hoping things return to “normal,” whatever that was. If we don’t fundamentally reimagine our relationships to each other, to our work, to the people and systems who are tasked with running things…well, the next time something like this happens it will be even worse.

But again: we’re not there yet. We have time, and a chance. One of the people who is thinking through how we might do things differently is my friend Benno Martens, a neighborhood and community planner in Ohio. His own most recent newsletter gets to the core of the problem of trying to just do the same things again once this particular illness stops rearing its head:

I think what we’re seeing is the folly of forty years of mass privatization and disinvestment in public goods. As state and national leaders have stripped our shared societal goods down in reckless pursuit of tax cuts and profits for corporations and the wealthy, ordinary people were left vulnerable to exactly what we’re seeing play out now across the country as a result of the pandemic…I mean by public goods the things we all share in providing for our society. Right now, we’re seeing how disinvestment and privatization effects our health in the form of brick and mortar hospital facilities, medical equipment and supplies, and healthcare insurance being tied to employment.

So to change that we have to start thinking about things a little differently. He continues:

There are so many other numerous examples of valuable public goods that we’re being reminded of now in addition to healthcare and pedestrian infrastructure. Public transportation, public media, retirement, childcare, unemployment, basic shelter and nutrition; each of these things can be a public good if we so choose to invest in them, and the lessons of the novel coronavirus outbreak suggests that we should.

There have, at many points in the past, been at least nominal efforts to do just what Benno suggests above: make public investments in the public good. The problem—and this will come as no surprise to anyone who has read a single previous issue of this newsletter—is that the logic of capitalism dictates that these unprofitable programs are the ones most worthy of trimming from bulky state and federal budgets that both parties tell us must be wrangled and tightened.

Another friend, Andrej Markovcic, wrote about this in Jacobin this week. The popular media narrative surrounding this crisis, Andrej points out,

could easily lead one to believe it’s only the worst-hit countries that were able to learn and make preparations. The rest of us just didn’t realize how bad it could get.

But that’s not true. California did realize, way back in 2006, what could happen if they didn’t invest in advance preparation for a major health crisis. That year, the state invested $400 million to shore up the state’s capacity to respond to a major pandemic or natural disaster. They built three mobile crisis hospitals that could be deployed around the state and amassed a stockpile of emergency medical equipment such as the now critically undersupplied N95 masks, ventilators, and 21,000 hospital beds.

Unfortunately, that foresight was thrown out the window in 2011, when Jerry Brown and the Democratic Party that controlled California legislature passed an austerity budget. The 2008 financial crisis had devastated state revenues, and among massive cuts to state services was the meager $5.8 million annual expense of maintaining the mobile hospitals. The program was cut, the highly equipped mobile crisis centers were turned into “high-end tents,” and the remaining stockpiles were either given away to hospitals or simply disposed of.

Our trust in the built environment is eroding as that environment itself erodes. But it’s important to keep in mind that this erosion is not a cosmic stroke of bad luck nor a biological misfortune. Capitalist austerity takes two Jenga blocks off the bottom row and then puts in the lowest bid for building the tower again—without those two bottom blocks.

Alright enough about that. By and large I am a crow sitting in a cherry tree, preoccupied with death and memory while shrouding myself in the fleeting and beautiful things of this world.

One of those beautiful things was John Prine. God, how beautiful. I was out running when the news broke that he had died. At the time I was running it was just starting to get late and the sun was that long, low light that you get on cloudless warm-weather evenings. That melancholy, aching, passionate kind of light. It was on evenings like those that I fell in love with John Prine’s music during my freshman year at Ohio State. I watched Into the Wild for the first time that spring and had to know what the song that Chris and Tracy duet on at the trailer park was. It was “Angel From Montgomery”—the original live version with Bonnie Raitt was the one my search led me to first—and I was on fire from the first chord. Hearing it still takes me back to 2009 and those frenzied aches of freedom.

Speaking of Bonnie Raitt: I think one of Prine’s biggest talents was the way that the songs he wrote made space for other musicians to shine. Iris Dement, Sturgill Simpson, Brandi Carlile, Raitt—he complemented each of them beautifully, and they him.

Maybe that’s the lesson for this week. To think hard about how you can act so that others shine.

“Ya' know that old trees just grow stronger

And old rivers grow wilder ev'ry day

Old people just grow lonesome

Waiting for someone to say, ‘Hello in there, hello’”

Take care of yourselves.

-Chuck