I Want To Know There Was Something Worth Missing

Do you and I have as much attention as we need?

A few weeks ago I wrote about the idea that paying attention to the small details of things was something akin to an act of faith.

In addition to its role in faith, I think paying attention is among our best remedies for minute anxieties, boredom, and other minor ills. Case in point: over the weekend I took a road trip to Montana with one of my best friends for a music festival that I had been looking forward to for a year and a half. (The event was supposed to happen in 2020 and was, obviously, rescheduled.)

But in the day or two leading up to the trip I was thinking very little about the lineup—which contained three of my five favorite living musicians—and was instead consumed with a dull sort of dread regarding the length of the drive. It’s a full day’s haul from Seattle to northern Montana, and while I don’t mind driving, I am not good at being a passenger. And in either role that’s certainly a long time to be sitting down.

The natural inclination in such cases, during one’s needed turns in the passenger seat, is to look for distractions. A book, your Twitter feed, et cetera. Those crutches that on some level support the idea that the long drive is something to be endured, rather than savored. In an effort to combat my dread I promised myself that I would try to appreciate the drive on its own merits. If I tricked myself into thinking that it was something to be looked forward to—well, it might not make the car go any faster, but I might be happier, which amounts to basically the same thing.

So I paid attention to everything I could: the afternoon light on the Cascades, the bumper stickers and license plates. (Montana seems to have a few dozen different official plates.) The tumbleweeds and dust devils in Washington’s high scrub plains. The minute details in my conversations with Tim. The names of places, like Ritzville and 4th of July Pass and Hot Springs. The impossibly clear depth of Flathead Lake from its western shore.

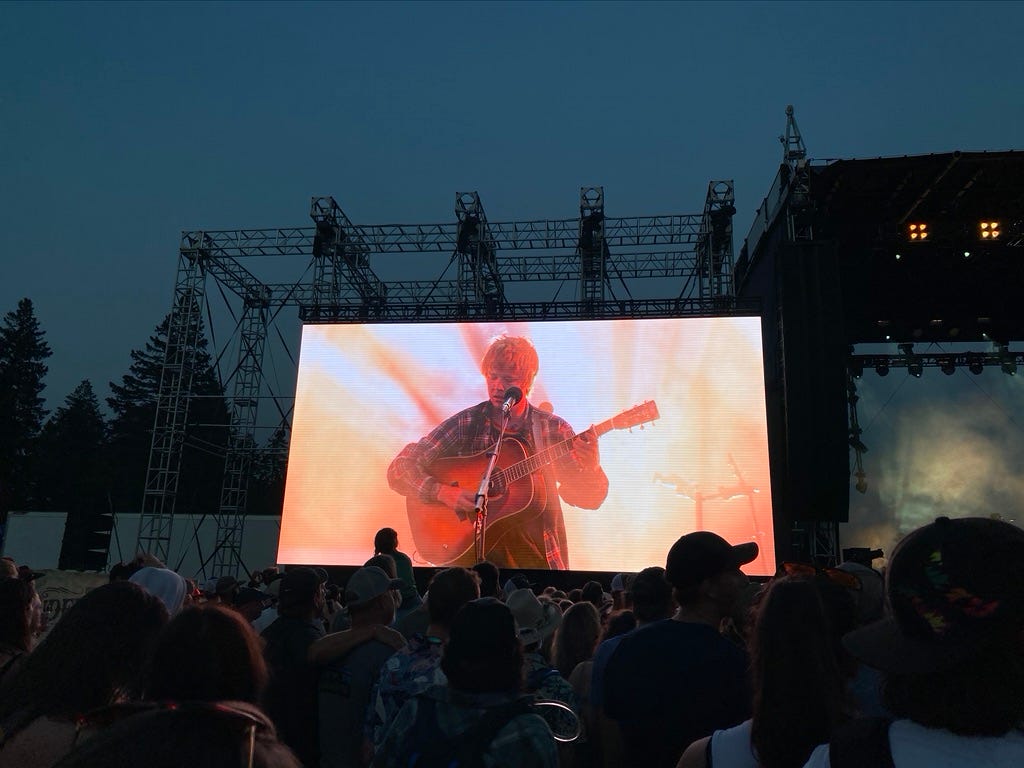

Without cell phone reception up in Whitefish, this trick carried over through the rest of the weekend, too. I paid attention to what was happening with the other two friends we met up there, who I hadn’t seen in a year. I paid attention to the life stories of our neighbors at camp. Paid attention to the performers and their idiosyncracies: Emmylou Harris standing straight-backed and regal on stage, then crumpling into a limping stoop as soon as her set was done. Tyler Childers figuring out, in real time, what to do with his hands without a guitar in them. Billy Strings demonstrating, in real time, what to do with his hands with a guitar in them.

The poet and essayist Devin Kelly wrote about this kind of thing recently. I often fall behind on Devin’s newsletters because, fittingly enough, I never want to open one if I’m not sure I can give it my full attention. He sustains an enviable level of insight and clarity across missives that are even longer than mine.

I’ve learned things from poems for the same reason people learn about anything: because they’ve spent quality time with it. When you sit with a single poem for a long time, when you type it out, when you speak it, when you try to unpack a line or feel the way a phrase fills your mouth, you begin to notice more about what the poem offers outward. When you pay attention — to anything, really, that has also been paid attention to in its creation — then the act of attention does not serve as an act of narrowing. Rather, it’s an opening — a givingness, to use that word again. All these doors open up the more you pay attention. They open out to light. They open to other rooms, other floors. They open to a hidden staircase. Another door.

I don’t say all this to make some curmudgeonly point like our dang phones are ruining our lives and our nation’s children or whatever. Really I just mean that this paying attention is clearly a skill that can be practiced, and relatively easily at that. And in that practice is a chance to open oneself up to larger, richer truths and possibilities. (I don’t want you to give up your phone and I don’t want to give up mine. In truth this method of full attention is pretty exhausting and it was nice to get back into internet-connected society and let my brain soak in mindless Instagram posts when the weekend was up.)

Devin continues:

I practice paying attention to a poem every week because I want to miss the world when I am gone. I want to know there was something worth missing, something beautiful, worth criticizing…I don’t want to tell myself that I know everything, that I can no longer be surprised. So I read. I’d encourage it. It makes me want to look, and keep looking, for as long as I can.

It takes sincere effort to gnaw life to the marrow or smoke it to the filter or whatever other oral metaphor you prefer for making the most of things. And I think he hits on just why that’s so important and necessary: there is only a finite and unknowable amount of time we have to poke around and look at stuff, and so be able to assess honestly the value of what we might miss when we’re gone (whether we have that ability or not).

As I said, for people like me this cannot be done at all times—in fact, I think I require the downtime, the occasional mindless scrolling hour, to fully process and appreciate those things I have sought and paid attention to, not to mention needing to restore myself for the next outing.

But how scarce is our attention, really? Devin Kelly points to the relentless commodification and division of it as a serious problem. Another prolific newsletterist I enjoy, L.M. Sacasas, provides an alternative for how we view our available attention, in an edition titled “Your Attention Is Not A Resource”:

Attention discourse proceeds under the sign of scarcity. It treats attention as a resource, and, by doing so, maybe it has given up the game. To speak about attention as a resource is to grant and even encourage its commodification. If attention is scarce, then a competitive attention economy flows inevitably from it. In other words, to think of attention as a resource is already to invite the possibility that it may be extracted…So here is a proposition for you to consider: you and I have exactly as much attention as we need. In fact, I’d invite you to do more than consider it. Take it out for a spin in the world…But it may be, too, that my initial proposition requires a qualification. Let’s put it this way: you and I have exactly as much attention as we need at any given moment provided that at that moment we also know what it would be good for us to do.

Little did I know that such a thing as “attention discourse” was an identifiable phenomenon, one in which I am now a participant. Anyway, I don’t think these two ideas—contradictory as they might seem—are actually at odds, in the end. The qualifier that Sacasas ends with is the key; perhaps it’s not just practice paying attention (generally) that we need, but practice paying attention (specifically). That seems to be at the heart of Kelly’s piece, too, and it’s clear that he’s found what that means for him: poetry, among other things.

I’m still working on what that means for me. But what I do know is that going looking for it has made me a more complete version of myself—happier, and more forgiving of others’ foibles (not to mention my own).

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be.