It Is A Bit Of A Trick To Keep Your Knowledge From Blinding You

What explanation of an aurora can be as satisfying as no explanation at all?

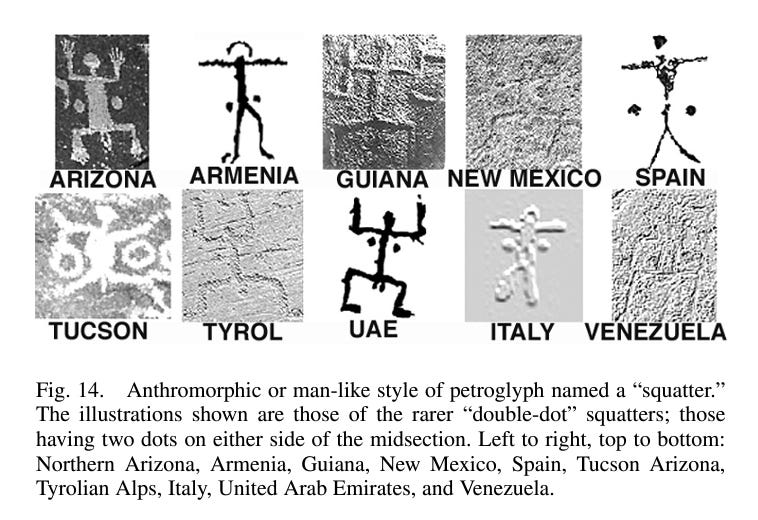

There’s a theory—just a theory, mind you—that the bizarre congruities between prehistoric rock art across the world can be partially explained by the presence of a persistent, intense aurora that affected the night sky for decades or even centuries.1 Researchers have found similarities (some more convincing than others) between the shape of the waves generated by high-energy plasma “Z-pinches” and the recurring shapes found in petroglyphs in places spanning from Minnesota to South Africa to Kashmir to Peru. These are not random squiggles, dots, and curves, this theory posits. Rather, the diverse and scattered pre-civilization peoples of the world were drawing from life: the shocking, vibrant displays that filled the heavens for them night after night.

I am frankly not learned enough to grasp the full scientific reasoning of the argument here, nor what I assume are the many rebuttals to be found elsewhere. But I find it important to consider, even if this particular explanation turns out to be hokum.

In case you missed it, it’s been a pretty big few weeks for watching the sky. Between the solar eclipse in early April and this week’s stunning (and stunningly far-reaching) aurora, more people than at any other time I can recall have been given cause to look up and wonder, all over the world, all at once. The pictures that have flooded my social media feed, and presumably yours, have been a testament to just how many of us are participating in these celestial events.

It would be easy, obviously, to be cynical about this. To think that people are just in it for the likes, or because it’s trending, or whatever. It would be easy, but it would also be dumb. Things trend online for all sorts of reasons, oftentimes vapid and/or cruel, but the fact that anything ever goes viral at all is because at our core we are a species for whom meaning is socially constructed. We are desperate to share the things we find—to tell others, hey, I looked at this thing, maybe you should look, too. At the heart of sharing things online is a need for participation, a need to not be left out or left alone, and while the results are mixed the essence of it is, I think, wonderful.

As for the eclipse and the aurora: there is something to be said for a collective act of bearing witness, especially to those things that, while technically explicable, still awe the rational mind, to whatever extent we have those. “Usually it is a bit of a trick to keep your knowledge from blinding you,” writes Annie Dillard, “But during an eclipse it is easy. What you see is much more convincing than any wild-eyed theory you may know.” It is also important, in what has been a historically bad year for the human race, to recognize that there are still forces out there—forces beyond our control—that can stun us all into the joy and reverence commensurate to what the universe has to offer us. On the day of the eclipse, my wife and I walked down to the Detroit River, planning to observe the sky from the top of a big hill in the park. I’m embarrassed to admit that my first reaction was annoyance at how many other people had had the same idea; I had imagined myself a silent sentry, meditating through the peak of the coverage (something like 99% of totality here) and feeling spiritually renewed by the stillness. Instead the hilltop was crowded with families. But I quickly realized, as the sky hurtled towards twilight in the middle of the afternoon, that I was exactly where I was supposed to be. Watching the moon slide in front of the sun, feeling the eerie chill descend, became cause for a party: there were whoops and gasps, there were stunned screams from children—anything but the monkish scenario I’d envisioned. And it filled my heart, it really did. That a whole community could come together for an hour so that we might all look up, and point at the same thing, and say Did you see that, even though we already knew the answer.

There’s a biography of the poet Robert Hayden called From the Auroral Darkness. I haven’t gotten my hands on a copy but I love the title because of the possibilities it suggests, that a poem, like an aurora, like a life itself, can burst forth and display something so wondrous that it renders our factual explanations irrelevant. These are the moments that make me feel holy, that make me understand the idea of spirituality and belief. Of the aurora, what explanation of facts and data could be as satisfying as no explanation at all? Celestial events, perhaps because they are so stunning, perhaps because they render us so clearly out of our depth, are fundamentally events of feeling, and so practically defy description—although, being human, our descriptions are the only way we have of relating those events to each other. “Seeing a partial eclipse,” continues Dillard, “bears the same relation to seeing a total eclipse as kissing a man does to marrying him, or as flying in an airplane does to falling out of an airplane.”

There’s a tendency in these moments to say that something like an eclipse or aurora makes you realize just how small and insignificant you really are. I am sympathetic to this idea but I ultimately reject it. We are not made small in the presence of the ineffable. We are a crucial part of the ecosystem, as creatures capable of wonder. These events have meaning, at least in part, because we exist to give them meaning. (It wasn’t until recently that I’ve realized where I maybe come down on the if-a-tree-falls-in-a-forest question.) What a miracle it is, that solar storms exist in the same universe as complex eyes capable of detecting, or perhaps creating, a great range of colors. What a miracle it is, that total eclipses fall upon a planet populated by beings for whom darkness and light hold ancient and special meanings, whose skins detect warmth and cold alike.

It isn’t just us, either. To the degree that we can claim to understand the behaviors of other animals, we are certain that many experience awe. Bears, anecdotally, have been observed seeking out high vantage points on hills and mountains from which to do nothing but sit and look out at everything below. It is dangerous and narrow-minded to anthropomorphize too much, but it is also dangerous and ignorant to believe that the emotions we claim for ourselves are ours alone. Love, grief, affection, memory, fear: it is not hard to see these things in our fellow creatures. It stands to reason that we can’t rule out their capacity for awe, either.

The sublime, the ineffable, call it what you like: despite my love of words I am overjoyed that there exist a few that point to that for which there are none. Seneca once wrote something to the effect that light griefs are loquacious, but the great are mute. I suspect the same to be true of wonders.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next time.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

Appreciators of real cinema will note that this is also the governing logic behind the 2012 film Prometheus, although the explanation there was “ancient alien civilization.”