It Would Be Proper To Grasp Your One Necessity And Not Let It Go

Everyone else is a foreign country.

Yesterday I was talking to a friend about two other friends’ writing—writing that somehow makes experiences that are unknowable to us relatable and accessible to us— and came to the conclusion that everyone else is a foreign country, for the most part. You might not understand every bit of it, but you can still be awed by it, move to it. Adopt the language and the culture as your own, or at least take an earnest stab at learning them, even as you know there will always be a piece of it that is beyond your grasp.

At bare minimum you have to cross state lines. Work a little harder to remember the exit numbers and whether you’re allowed to pump your own gas and how likely you are to get pulled over for speeding, even if you’re on your way to someplace you’ve been a hundred times before, someplace comfortable.

Anyway I’m trying real hard to remember that. Instagram, a medium through which I engage with good number of people in my life, has become borderline unusable for me lately, though my distaste for it has not caught up to years of habit in that regard—I still compulsively watch stories when I can’t think of anything else to do. (Which is, I suppose, why the feature was created.) It’s just that I see less and less of what’s going on in the lives of the people I care about and more and more of the same surface-level information about the things happening in the world that everyone—or at least everyone who’s on Instagram—already knows about.

I can’t help but wonder: who is this for?

L.M. Sacasas, who creates yet another of the umpteen newsletters I subscribe to, wrote about this problem last week:

My point turns out to be relatively straightforward: may be you and I don’t need more information. And, if we think that the key to navigating uncertainty and mitigating anxiety is simply more information, then we are probably going to make matters worse for ourselves.

Believing that everything will be better if only we gather more information commits us to endless searching and casting about, to one more swipe of the screen in the hope that the elusive bit of data, which will make everything clear, will suddenly present itself. From one angle, this is just another symptom of reducing our experience of the world to the mode of consumption. In this mode, all that can be done is to consume more, in this case more information, and what we need seems always to lie just beyond the realm of the actual, hidden beyond the horizon of the possible.

And, once again, this mode of being, with regards to navigating uncertainty, has the paradoxical effect of sinking us ever deeper into indecision and anxiety because the abundance of information, especially if it is encountered as discreet bits of under-interpreted data, will only generate more uncertainty and frustration.

Knowing things is, more often than not, better than not knowing things. But what does it actually mean to know anything? Can the appropriate amount of information, nuance, layers, cultural context, or other core components of knowledge be conveyed by something as simple as a slide deck on a tiny screen? Moreover, can the kind of critical thinking required to situate that knowledge in any sort of meaningful context be accomplished in the time it takes to click through to whatever the next thing is? I’m dubious, on both counts.

One of the most popular accounts doing this is called So You Want To Talk About... (@soyouwanttotalkabout), which I think unintentionally drives home the point I’m making. People could reasonably be assumed to want to talk about many of the things featured on the account. But that is precisely not what they are doing. They’re not talking with anyone; they’re passively consuming an easily digestible viewpoint. Actually talking about something, with other people, does allow us to deepen our knowledge and refine our thinking and add context we might otherwise have missed. It also forces us to define for ourselves why we believe the things we believe, so we might explain our position to other people.

(Perhaps I’m being too misanthropic and the folks viewing those slides are taking those conversation topics out into the real world, to the people in their own lives. I’d certainly like to think so.)

But on top of all that: It is not enough to know things. You also have to do things. And doing anything that actually has any power to make the world better probably does take more time than you’d like it to. It also mostly requires subsuming oneself to a larger organization or project, transformationally so. This all feels like a cousin to the ontological quandary of what it means to be a good person. We, as a culture, seem to be proponents of the view that good intentions and good thoughts are what make a good person. But what good is it, being that kind of good person, if you’re not actually doing good?

No one escapes being a hypocrite at some point and I do confess to sharing things when I feel like they’re socially and politically important. And for people who have historically been denied a platform—well, I certainly don’t begrudge them using whatever space they can get their hands on. But I have an increasing suspicion that in general we’d all be better served if we rebuilt some of the barriers between what we consume for entertainment and what we aim to consume for a larger purpose. There are places where these categories overlap, certainly; when I read an especially good poem, for instance, it often creates feelings in me that I want to act on and share with the world in some way. It’s not just entertaining, it’s fulfilling.

I have to think that we’d be better off chasing those feelings, that fulfillment, than spending our time convincing ourselves that we’re making the world better through posting.

I don’t mean to pick on the people who do this, and if you feel like this is about you, I apologize. Clearly I have my own neuroses to work through; besides, the root of the problem is structural, not personal. This complex survives because it is borderline offensive to our American sensibilities to hear, when presented with a problem, that there is nothing that we can do about it individually. We love to believe that we are uniquely equipped to move the levers of the world ourselves.

Do you remember the starfish parable that you learned as a kid? The “I made a difference to that one” story? As I’ve gotten older I’ve found myself less and less satisfied with it as any kind of useful lesson for existence.

The more immediate reason why I find it unsatisfying is that yes, a handful of those thousands of starfish would get another chance at life thanks to the child’s patience and largesse, but his approach is hardly a solution to the actual problem at hand. Are we to take this tiny percentage as a triumph? (Maybe, if the last year is any indication.)

The bigger reason I find the story so unsatisfying is that those starfish on the beach fell victim to massive natural forces with inevitable power. Tragic, yes, if you treat all life as precious, but ultimately a fate in line with the machinations of the universe. Our own societal trials and tribulations share none of that natural character, none of that inevitability. (“We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings,” said Ursula Le Guin.)

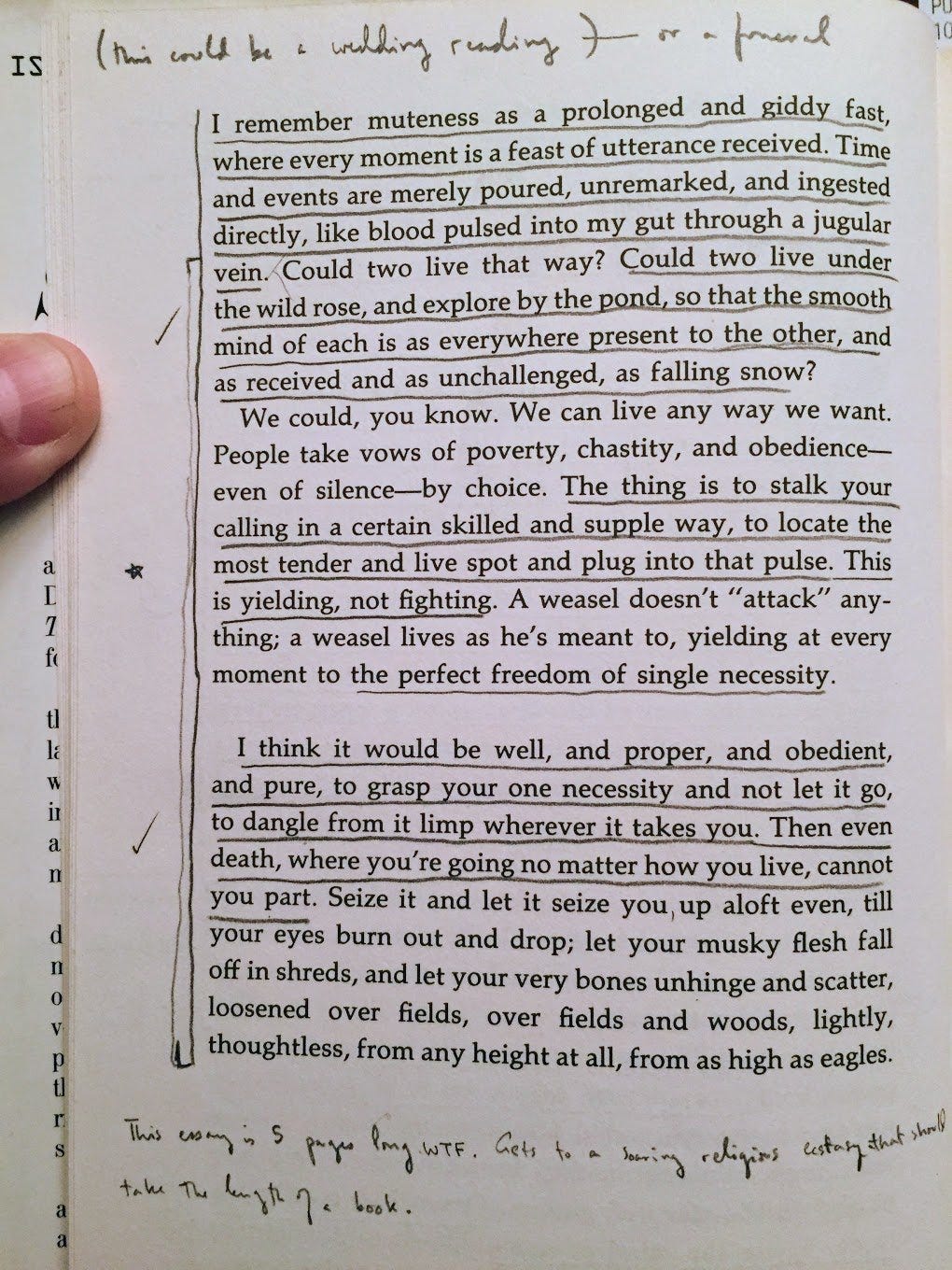

I think if there is any way out of what ails us, it is rooted in this necessary presentness that Annie Dillard writes about. This is another thing I am trying to remember to work on. Grasping those necessities—for I have never had just one—and not letting them go. Letting my life be guided accordingly. (“Not the potter, but the potter’s clay!”, like Johnny’s mom said in The Dead Zone.) Love, solidarity, comradeship, whatever you want to call it: it all requires taking that first brave step into foreign lands so that you might better understand who and what you’re fighting for, and not putting it on yourself to win that fight alone. (You won’t!)

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be.