I have a million and one memories of the day I got married, but one in particular has been at the center of my thoughts this week.

My wife and I had purposely opted out of a seating chart, hoping the people we had invited from all over the country, who we knew in all sorts of ways, would gather in new and interesting combinations that would turn more of our friends into each other’s friends. After the formal portions of the reception were over and the only agenda items involved dancing and singing and the open bar, a few of my college buddies sheepishly approached me.

“Hey man,” they said. “That old guy at the end of our table really isn’t happy with us.” I looked where they were pointing and saw my family friend and mentor, Norm.

“Why not?”

“We weren’t really paying attention to your first dance, and we were just talking and laughing at something else, and he chewed us out pretty good for disrespecting you.”

I laughed and told them not to worry about it, and we all moved on with our evening, but I have thought about that incident here and there over the years. And this week I have thought about it almost constantly.

Norm Andrzejewski died on Sunday at eighty-two after a battle with stomach cancer. My wedding day was the last time I ever saw him. The last thing he ever did for me, at the close of many years of doing things for me, was defend the solemnity of my love, the seriousness of my special day. I didn’t care what my friends had done—the first dance is really only for a few people, and I am in such a constant state of half-embarrassment that our guests not paying attention was frankly preferable—but I care very much that it meant something to Norm, enough for him to defend it as fiercely as he defended so many other people and things in the course of his life.

I met Norm when I was 16. A year and a half earlier, Hurricane Katrina had devastated the Gulf Coast, and in response Norm had founded a volunteer organization based in Syracuse called Operation Southern Comfort. My mom had gotten involved right away, and in April 2007 I joined her and Norm and twenty-some other people on a trip down to New Orleans to gut houses and hang drywall and, as I would learn, do the equally important work of listening to the stories of the people we met. To break bread with them and cry with them and with the work of our hands try to restore their hope and alleviate their suffering. Care work, in other words, disguised as manual labor. (Though as my friend Devin Kelly reminds me, most of the latter can be reframed as the former, and doing so might give us a deeper appreciation for the world itself.)

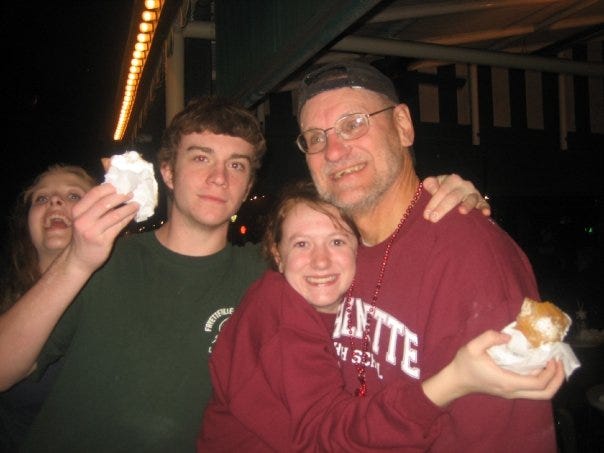

During the following year I went to New Orleans with Norm a few more times.1 Each trip was a marathon drive—twenty-two hours from Syracuse to Chalmette or Belle Chasse or the Eighth Ward, with an overnight stop at the Virginia/Tennessee border sleeping on the floor of a church gymnasium. He was a leader who encouraged love and openness but tolerated no nonsense, no distractions from the Work we were there to do. He could be intimidatingly stern—the life of a teenager is basically a constant pursuit of nonsense, of distractions from the Work—but he also put in longer, tougher hours than anyone as we mucked out destroyed buildings and spackled and roofed. A general on horseback leading the charge into battle, not sending others to carry out his vision from a safe distance.

Each trip ended with a candlelight vigil, usually at the Knights of Columbus hall where we took our meals during the week. Norm wasn’t much of an orator; really, he was a chronic mumbler who interrupted himself constantly by chuckling at the wonder of it all. But he set the tone for all of us by opening and closing these ceremonies at which all who were moved to speak were invited to do so. A strange collection of people, maybe: northern high schoolers and suburban families taking advantage of holiday breaks, rednecks and swamp people, poor Black folks who had lost everything and then some in the biggest storm in living memory. Norm brought us all together in the shared experiences of loss and hope and community, and invariably brought us all to tears. “It’s a beautiful thing,” was his constant refrain. I can’t think of a more fitting description for those moments, nor a more fitting epitaph.

Norm’s passing leaves a hole in the world. How many people do you meet in a lifetime who dedicate their every waking moment to bettering the lives of others, most of whom will never even know their name? How many people do that, not just in the wake of devastation, but for years and years after that devastation has left the headlines and the rest of the world has moved on? I feel profoundly lucky to have known Norm, to have learned from his example. I grieve his passing. But his death—just like his life—is as good a motivator as I can imagine for getting back to the Work, with love and without distraction.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next time.

-Chuck

When I got to college, I leaned on Norm and his by-then vast network of contacts to start leading my own trips down there. He got us set up with jobsites, with tools, with the families and neighborhoods where are our contributions would make the most impact. (He also didn’t even get upset when I had to call to tell him our group had failed to lock up an expensive generator we’d borrowed, which was stolen almost immediately.) He really knew how to divide the work, and multiply it.

Thanks, Chuck. Godspeed and rest well, Norm. 💜

Loved this deeply -- thanks for your words and memory of Norm.