Note: this is the second in a series of travel pieces about places that mean a lot to me. The first, about the Olympic Peninsula, can be found here. The piece below is long, by far the longest I have published in this newsletter, but I hope it will be worth it. And there will be a pie recipe to accompany it tomorrow.

I do not know what time it is. I have not carried a real watch or a phone all this year; I keep a plastic stopwatch in my classroom and another by the woven reed mat that separates my futon mattress from the plastic bedroom floor. Neither is here with me on the boat. I know only that it is nighttime, the deepest variety of nighttime I have ever known, stars spilled so richly across the sky that every horizon seems to glow.

It is nighttime, and we are flying. The aluminum skiff cuts rhythmically across the soft waves of the ocean with a whunk whunk whunk that would keep me awake even if I weren’t so delirious with adrenaline that I feel like I might never sleep again. In daylight the water beneath us is a clear and piercing blue and you can see to impossible depths. In the darkness it feels different—solid, almost. Menacing and comforting all at once.

There are seven of us in the boat. Six when we started: Timothy, Andy, Melioñ, Herby, myself, and a man whose name I never catch. Seven now, the heaviest passenger the one we picked up on the way: a sea turtle. Massive, rugged, endangered. He will feed a few whole wato, neighborhoods, for days. (This is not the biggest turtle in world history or anything like that; in a land where everything, the people included, is small, a wato might be two or three houses.)

Herby—pronounced air-bee—is my neighbor, a big man, jovial and crass. A month ago, he and his wife named their newborn baby after my mother, insisting that the honor was theirs, not mine. Melioñ—pronounced mel-ee-ung, though he goes by Manny—has this year become my best friend, my therapist, my confidant, and my translator. Four of his children are my students.

Andy is our pastor. The wildness of the idea that I am out hunting endangered species with a man of the cloth is not lost on me. In any other context that would seem abhorrent, opulence and decadence and waste made manifest. But not here. Here there is no capital-c Church, no gilded bibles and statues; the pastor wears no finery, just a clean white button-down. And it is not the fault of the people here that the sea turtle is endangered; they have hunted these magnificent creatures sustainably in their own waters for millennia.

These are the Marshall Islands, these people are Marshallese, and their ways are their own.

The Marshall Islands are so small and scattered that many renderings of the world don’t even label them. They sit out in the central Pacific, just across the intersection of the International Date Line and the Equator. “Where they used to draw sea monsters on old maps,” I told friends in the months leading up to my departure for an English teaching position there.

Fifty-eight thousand years before the birth of Christ, the first successful campaigns of exploration from Southeast Asia began to spread across the Pacific. We can’t know how many of the intrepid souls that sailed out into the vast unknown succeeded in finding new lands, how many were consigned by storms or hunger or sharks or bad luck to nameless graves in blank spaces bound by nothing but the horizon. What we do know is that enough of them made landfall on coral atolls to settle the region now known as Micronesia, which includes the Marshall Islands, right around the time BC gave way to AD.

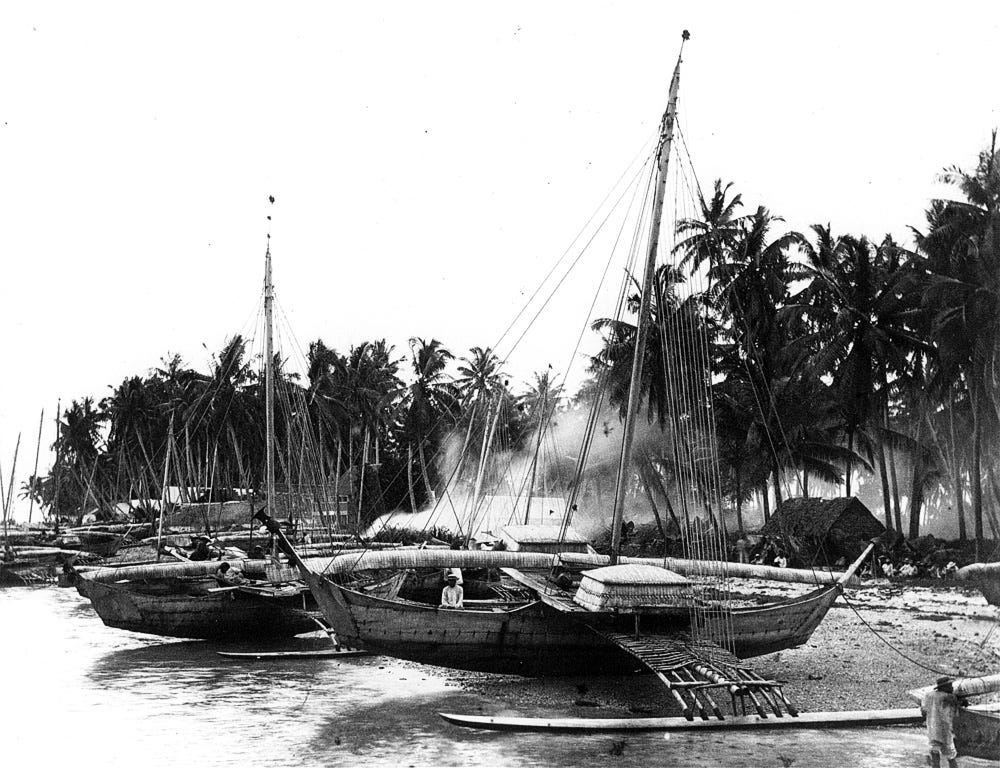

If you’ve seen the movie Moana, you’ve seen outrigger canoes like the ones that these voyagers used; similar crafts settled Polynesia as well as Micronesia. They vary in size, from the quick personal korkor to the practical small group tipñol to the massive walap, which can hold up to fifty passengers. (Moana went out on a korkor but at the end of the movie the whole island sets out on a fleet of walap, if that helps.)

Outrigger canoes are so called because they have an appendage, an outrigger, that branches off the main body of the canoe as a lightweight means of stabilizing the craft. Thanks to this appendage and their clever sail—which sits in a notch at either end of the craft and can be switched quickly to the opposite side to change the canoe’s direction—outriggers are light enough for low-maintenance lagoon cruising, but rugged enough for traversing the rough and chancy open ocean.

The Marshallese perfected the art of sailing these canoes from place to place with a navigational precision that astounds the modern mind, the horizons of which are in many ways limited, not expanded, by our technologies. In darkness they could sail with the stars, but in the daylight or on cloudy nights they could still traverse hundreds of miles of open ocean and arrive exactly at their destinations.

These master navigators accomplished this not by magic or intuition, but through the cultivation of complex mental maps and a staggering degree of mental and physical attention to their surroundings. In 2015, a team of scientists and a reporter for The New York Times joined the man who is now the country’s last living (unofficial) ri-meto, Alson Kelen, for a voyage to try to pinpoint the method.

Swells generated by distant storms near Alaska, Antarctica, California and Indonesia travel thousands of miles to these low-lying spits of sand. When they hit, part of their energy is reflected back out to sea in arcs, like sound waves emanating from a speaker; another part curls around the atoll or island and creates a confused chop in its lee. Wave-piloting is the art of reading — by feel and by sight — these and other patterns. Detecting the minute differences in what, to an untutored eye, looks no more meaningful than a washing-machine cycle allows a ri-meto, a person of the sea in Marshallese, to determine where the nearest solid ground is — and how far off it lies — long before it is visible.

In 2015, when the team set sail in a modern boat trailing Kelen in his korkor, one other wave pilot still lived—Korent Joel, who, like Kelen, was not officially a ri-meto because he had never passed a navigation test laid for him by a previous ri-meto. In Joel’s case, it was because his home of Rongelap Atoll was evacuated due to fallout from American nuclear testing just as he was mastering the art. It was Joel who had pled for more scientific research into wave piloting, so that it might be understood and not lost to history.

Joel immediately asked Genz to bring scientists to the Marshalls who could help Joel understand the mechanics of the waves he knew only by feel — especially one called di lep, or backbone, the foundation of wave-piloting, which (in ri-meto lore) ran between atolls like a road.

But when Joel took Genz out in the Pacific on borrowed yachts and told him they were encountering the di lep, he couldn’t feel it. Kelen said he couldn’t, either. When oceanographers from the University of Hawaii came to look for it, their equipment failed to detect it. The idea of a wave-road between islands, they told Genz, made no sense.

Privately, Genz began to fear that the di lep was imaginary, that wave-piloting was already extinct.

Of course, this wouldn’t be the first time that the keepers of Western knowledge had discounted the stories told by the indigenous people at the corners of the world, only to find out much later that they had been correct all along. In the story of the wave pilots are echoes of many others: The Aboriginal Australians, who for 10,000 years passed down an oral story about a giant wave that washed away the world and its people, scoffed at by centuries of white settlers—until geologists and linguists confirmed that massive post-glaciation tidal waves swamped the precise areas where the stories originated, back when there were less than 10 million people on the planet. The Makah and other tribes of the Pacific Northwest, whose own oral traditions recounted the precise details of the last “really big one,” an earthquake and ensuing tsunami that changed life in that region forever. The Netsilik Inuit of the Canadian Arctic, who had known for 150 years where the “lost” expedition of the HMS Terror and HMS Erebus had ended up before they were “officially” located in 2014 and 2016.

There is more than one way of knowing, after all.

As they mapped the coordinates Huth had recorded atop van Vledder’s model of sea conditions, they found that the path they had taken was exactly perpendicular to a dominant eastern swell flowing between Majuro and Aur. And at places where the swell, influenced by the surrounding atolls, turned slightly northeast or southeast, the path bent to match. It was a curve. Everyone had assumed that a wave called ‘‘backbone’’ would look like one. ‘‘But nobody said the di lep is a straight line,’’ van Vledder said.

What if, they conjectured, the ‘‘road’’ isn’t a single wave reflecting back and forth between every possible combination of atolls and islands; what if it is the path you take if you keep your vessel at 90 degrees to the strongest swell flowing between neighboring bodies of land?

Wave-piloting hadn’t gone extinct after all.

One Saturday morning I wake up to the sound of digging. My bed—a twin futon mattress on a woven reed mat—butts up against the outer wall, which is a thin sheet of plywood; I can hear shovel going into earth six inches from my head. The conversation I can hear through the screen window is lively, excited, panicked, and though I’ve been here for eight months I can’t understand a word of it at this speed. I dress hastily and am intercepted at the door by my host mom, Mili, who has a mug of tea and a cinnamon roll for me.

“Emej Katleen,” she says. Katleen is dead.

I get the story in slow chunks from some of the people milling around, who are willing to talk to me with a speed and simplicity that allows me to get the gist: there was a windstorm in the night that blew down a palm tree directly onto the small corrugated tin structure where Katleen had been sleeping. She was found with a broken neck or back, and carried here, the closest house, to be put into a shallow trench where traditional medicines and remedies might be tried in a last-ditch attempt to save her life.

This isn’t about you, I whisper to myself, but that doesn’t stop me from shuddering at the thought that fifteen minutes ago I was sound asleep less than a foot from a dead body. Not just a body—Katleen, my neighbor, the mother of three of my students. I can see one of them, her son Tammy, sitting at the base of the breadfruit tree in our yard. I do not go to him, even as it rips my heart in two to watch him stare glassy-eyed into space. The people of Aur are physically affectionate with their own children seldomly and with other people’s never. Hugging is an indicator of deepest intimacy, not a casual gesture of friendliness. Tears, too, are a rare sight outside of small children and funerals.

I am not here to violate the customs of the people who have taken me in, to prescribe my Western ways just to make myself feel better. They’ve had too many centuries of that already. For now it’s like Annie Dillard said: “I cannot cause light; the most I can do is try to put myself in the path of its beam.” So I drink my bitter tea and stumble to my classroom—where I am sure to be unbothered on a Saturday—and spend the day lying on top of the desks reading my way through a box of children’s books.

For weeks none of my students will come by the house, and my host siblings leave, too, sleeping elsewhere at night. The Marshallese have wholeheartedly embraced Christianity, but their practice of it blends missionary Protestantism with a much older belief that allows for the presence of all manner of spirits and demons. Most of the time the people here are indifferent to death, or at least not shocked by it; it is a real and regular feature of their lives. A week before Katleen’s death one of my third grade students carried a dead bird around for most of the day, its neck broken, because he had found it and was curious about it. But with the death of this woman no child (and many adults) will come near my house, indefinitely.

Simultaneously indifferent to death and haunted by the prospect of spirits and demons—a fitting contradiction for a people who have been forced to be pragmatic and hardy for millennia and now sit at the brink of an extinction not of their own making.

Coral atolls like those that make up the Marshall Islands are created when the living reef that forms around the base of an oceanic volcano builds upon itself even as the volcano becomes extinct, erodes, and disappears, a process which can take some 30 million years. The hard limestone exoskeleton of these corals forms the durable surface of the atoll; because of the irregularity of the process, the height of the atoll tends to vary across its length and over time most atolls cease to become solid rings and instead appear as several individual islands.

There are no towering atolls out there in the world. Coral has its limits. The average elevation of the Marshall Islands is less than three meters above sea level, with many smaller outer islands falling entirely below that mark. This puts the entire country at risk of indundation and permanent destruction as sea levels rise; the rare “king tides” whose might that all Marshallese people grow up respecting have become frighteningly common in recent years.

Three meters seems awfully high, you might be thinking, at least higher than the seas will rise. But a nation doesn’t have to be buried like Atlantis to be killed by the rapid melting of the poles. Even the occasional swamping of a corner of an island will irrevocably damage that island’s thin freshwater lens and poison the roots of its coconut and breadfruit and banana trees. The rainwater catchments of a place more drought-stricken with each passing year will not be enough to make up the difference.

I don’t like to espouse prophecies of doom particularly when they involve the people and places I love but the Marshall Islands are in dire trouble unless the world’s most serious climate plan becomes something better than the Paris Agreement, which in keeping with tradition does not challenge the stranglehold of international capitalism. (If I make literally everything I ever write about that, it’s only because literally everything is about that in some way or another.)

People who are headed in the right direction often say that it is folly to think that we can keep consuming the way that we do and expect anything to get better. “You’re Making This Island Disappear,” screams one CNN headline from 2018, the result of a journalist’s trip to Majuro, capital of the Marshall Islands. But like so much of the well-intentioned liberal worldview it misses the mark and mistakes a symptom for the disease. The way you and I consume certainly contributes to climate change. But our consumption is downstream of production, and it is that production—and more specifically, our relationship to it—that must be reordered if the Marshall Islands are to stay above water.

I find myself coming back frequently to Connor Kilpatrick’s “It’s Okay to Have Children,” the definitive response to the modern ethical quandary about bringing kids into a world where they will presumably be forced to exacerbate that which we are all guilty of, the poisoning of the planet.

More and more, liberalism finds itself unable to imagine any way out of the hell of life on the margins in 2018. Instead, they’ve begun to see their role as something like moral sentinels: piously observing and managing the collapse. It’s a liberal-left that no longer believes it can change the world and instead, in the words of Adolph Reed, finds its most important mission in simply “bearing witness to suffering.” They either believe a mass political challenge to capital and climate collapse is impossible, or simply undesirable. Either way, their answer is the same — not a revived labor movement but a new moralism of austerity and self-sacrifice.

I like to imagine a nation in which we are not paralyzed by guilt and moralizing about our helpless, privileged place in an unjust world and instead commit ourselves to building that world into one that can take care of us, and be taken care of by us. I am reminded of the words of de facto Marshallese poet laureate Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, who addressed the United Nations in 2014 with a poem she had written for her newborn daughter. It contains verses like this one:

dear matafele peinam,

i want to tell you about that lagoon that lucid, sleepy lagoon lounging against the sunrise

some men say that one day that lagoon will devour you

they say it will gnaw at the shoreline

chew at the roots of your breadfruit trees

gulp down rows of your seawalls

and crunch your island’s shattered bones

An annihilation of this sort is unimaginable. To be torn and scattered by the same force that has given your people life for millennia—the knife of irony never stops twisting. These ironies make way for others: take the Sovereign, or SOV, a cryptocurrency that the Marshall Islands is rolling out in partnership with an Israeli firm to “reduce dependency on the US dollar.” A noble aim, to be sure, were it not for the fact that cryptocurrency mining is increasing global carbon emissions at a staggering rate. Desperate times, desperate measures, and all that.

no one

will come and devour you

no greedy whale of a company

sharking through political seas

no backwater bullying of businesses with broken morals no blindfolded

bureaucracies gonna push

this mother ocean over

the edge

Maybe. If we can make it so.

It is nighttime, again. I am on the boat, again. We are skipping across the waves of the lagoon in the light of the impossible Pacific moon, again.

I am crouched in the bow of the skiff. Timothy sits at the stern, guiding the outboard motor with a practiced hand. Melioñ sits behind me casting the beam of a flashlight into the water. In my hands is the wooden handle of a net, the kind that looks like the lacrosse goalie’s stick.

We are on the hunt for flying fish, who are lulled to the surface in the moonlight and will take to the air if startled. To their detriment they can only do this in one direction, and we know that direction. Each time Melioñ spots one in his beam Timothy turns the boat, and it is my job to swing the net down in front of the fish as one of them slaps the water behind. A perfect system: they take flight directly into my net.

In an hour at the bow I catch nine of them. A respectable outing for a first timer, Melioñ tells me. I am beaming with pride. “We will take these to Mili,” he says. “She will make you a feast.” We switch places for the next hour, and he adds 50 more fish to the haul. I am a babe in the woods; he is an artist. But I am not upset or jealous—I am just happy to be here, spinning out across the waves under the stars, watching a master of his craft at work, watching one of nature’s bizarre works of miniature machinery take flight again and again in our wake.

Hemingway once wrote that “if you ever get so that you don’t feel anything when you see flying fish go out of water or when an elevator drops you better turn in your suit.”

I will get to keep my suit for the foreseeable future, it seems.

On March 1, 1954, the United States conducted the Castle Bravo nuclear test, detonating the most powerful bomb in our nation’s history. The explosion occurred in the lagoon of Bikini Atoll, in the northern Marshall Islands, which had been evacuated eight years earlier. The United States had taken possession of the Marshall Islands from the Japanese during World War II; two years later, those strategic outposts of the Pacific theater were repurposed for the further advancement of American military might.

When the Bikinians were asked to evacuate they were told by the naval commodore in charge of the islands that they were leaving, temporarily, for “the good of mankind and to end all world wars.”

Over a twelve-year period the United States dropped a total of 67 nuclear bombs on their new conveniently empty property. Three of those tests rank among the top 12 biggest manmade explosions in world history. And contrary to what the Bikinians had been told, their evacuation made room for an escalation into a permanent state of war from which the United States has never returned.

Castle Bravo, besides its historic size, is infamous for one other reason: the fallout spreading farther, it is claimed, than anyone had anticipated. (“We didn’t know” is somehow an acceptable substitute for “We didn’t care,” here in the US.) The radioactive coral dust spread hundreds of miles, resulting in the emergency evacuations of two more atolls, Rongelap and Rongerik, home to many displaced Bikinians. When the people of Rongelap were allowed to return three years later, it was to an atoll that was unrecognizable: the vegetation, the fruits, and the fish had all been killed or become so toxic that eating them made people violently ill.

In the seven decades since Bravo and the other tests the rates of cancer, birth defects, hypothyroidism, and other radiation-associated illnesses has remained orders of magnitude higher in the Marshall Islands than in the United States.

There is a sinister logic to all this: having dropped two nuclear bombs on civilian Japan the United States dropped a few dozen more on the Marshall Islands, a miniature genocide to increase our readiness and capacity for the final genocide, a full and complete annihilation of the world to save it from the Communist menace. (I don’t much go for Catholicism anymore but the fact that John F. Kennedy was able to stop the Curtis LeMays and Allen Dulleses of the world from achieving this end is a point in its favor.)

March 1 is recognized as Nuclear Victims Remembrance Day in the Marshall Islands, which is why this piece is coming out this week. A nation of just 60,000 has victims beyond counting. There are all the provable cases, of course. But how do you quantify the loss of a homeland to which you can never return, the loss of the fish and fruits that were the lifeblood of your people? How do you reckon with the horrifying truth that history repeats itself, as the dome where the Americans sealed the most identifiable nuclear waste has begun to leak back out into the water that surrounds you?

I spent a year of my life reckoning with questions like these. I lived in the Marshall Islands from 2012-2013, departing my own homeland a month after my college graduation and ending up in a country with fewer residents than my alma mater, Ohio State. I was there to teach English—my first gig of that sort—on an island called Aur, home to a grand total of 200 people.

When I signed up for the program that took me across the Pacific Ocean to that remote teaching post I was still very much steeped in the mindset that not only was I going to be a brilliant teacher from the first day, but that my teaching was going to change the lives of my students. They had had English teachers before me, but I would be the English teacher that made all the difference. That well-intentioned white savior thing, basically. (I had only chosen this program after being eliminated in the very final rounds of Teach for America selection, to which I had applied for similar reasons.)

But the longer I stayed and the more I learned about the history of the place that had taken me in, the more I began to question everything, including myself. Was I doing more harm than good by trying to cram kids into a method of learning and thinking prescribed by the same kind of people that had destroyed their country? Was learning English, of all things, the most useful thing that any of these kids in a remote fishing community could have been doing? And what right did I have to call myself a teacher, coming here wet behind the ears like this, when other people could clearly have done the job better?

These were all fair questions, as I look back at 21-year-old me. But like anything the questions being fair doesn’t mean the answers are simple. All of my hunches about the rot inside what I was doing were to some degree correct—and yet the people in that community took me in without question and cared for me as I bumbled my way through life in their midst. The United States is a bloated, heinous war machine that has ruined and reshaped the lives of the Marshallese—and yet to be an English-speaking American on Aur is to be a guest of honor. The Marshallese are steeped in American culture, but it takes strange forms. There were the more understandable obsessions, like Kobe Bryant and Marvel superheroes. But during my year there the most popular songs on Aur were The Bee Gees’ “Islands in the Stream” and, inexplicably, one-hit-wonder Eamon’s “Fuck It (Don’t Want You Back)”, to which I can still recall the lyrics to this day. (It’s catchy.)

There is a Marshallese expression I come back to again and again as I ponder these contradictions, almost eight years after I sailed out into Aur’s lagoon for the last time: Jouj eo mour eo, laj eo mej eo. Kindness is life, cruelty is death. This is not a statement of childish naivete but a simple truth for a people who have spent thousands of years enduring by banding together. People on Aur were kind to me not because I had earned it but out of habit, and that was enough.

I don’t know how it is on the other islands but on Aur, on your birthday, your closest friends and neighbors come by and sing to you and bring you food, and then they typically enter your house and take something for themselves rather than giving you a present. Notions of property are different there and the point is that whatever item is taken still remains in the community, which means you can still use it—it just lives somewhere else now.

Kindness is life, cruelty is death.

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter in your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be.

PPS - Stay tuned for a pie recipe to accompany this piece dropping tomorrow.

Hello Chuck. I really like your writing and am interested in getting in touch with you in regards to your book about your thru hike on the PCT. Here are my details: Howard Shapiro/ hshapiro54@gmail.com/360 941 6399/

I hope to hear from you. Thank you, Howard