I would like to tell you a story about a forest.

When I was a Boy Scout, one of the year’s biggest events was always “Stealth,” the mutant child of a campout and a game of capture-the-flag. At base camp, the adults would divide us up into two teams and then send us off into the Morgan Hill woods in opposite directions with a map and a compass. With no supervision, we were tasked with finding a suitable campsite, entertaining and cooking for ourselves, and then getting up in the morning to go hunt for the other team using our orienteering skills.

The thrill of the chase was secondary to the thrill of being free, for the first time in many of our lives, of any adult influence for a day and night. It was secondary to knowing that we were really and truly responsible for our own welfare, a few inconvenient miles from any help. Growing up tasted like evergreen air and burnt grilled cheese.

On one of these outings we returned to base camp with energy to spare. (Remember having energy to spare?) I don’t remember who won, or if anyone did. These contests ended in a lose-lose draw probably half the time. What I do remember is that within minutes we were in the midst of a full-scale pine cone war, pelting each other with the sap-soaked green missiles as we ducked behind tents, picnic tables, trees, cars.

I’ve been reflecting on that youthful hour lately, because in our outburst we may have ended up reshaping the future of that forest in ways that were beyond our comprehension back then.

Trees, as it turns out, can recognize their own kin. And this recognition has real implications, because what we also know about trees—something that western science had largely not accepted yet at the time of the pine cone war—is that they are deeply, inextricably entwined with each other. The order of the day among trees is not competition, but cooperation: a mutual network of resource sharing and communication carried out along vast networks of fungal threads that link the roots of trees beneath the surface of the earth.

Largely thanks to the work of a forester-turned-scientist named Suzanne Simard, we now know that this resource-sharing is not a blind and accidental process. Instead, the “mother trees” of Douglas-firs and red cedars and all sorts of other species allocate resources disproportionately to trees they are related to, even when other trees of the same age are linked up. While they live, they give a little something to all the young trees in their fungal network, but when necessary they prioritize this distribution to struggling seedlings of their own genetic line. And when they begin to die, they flood their children with as much carbon and nitrogen and other life-giving material from their own bodies as they can, hastening their own demise so that their progeny might live a longer, fuller life.

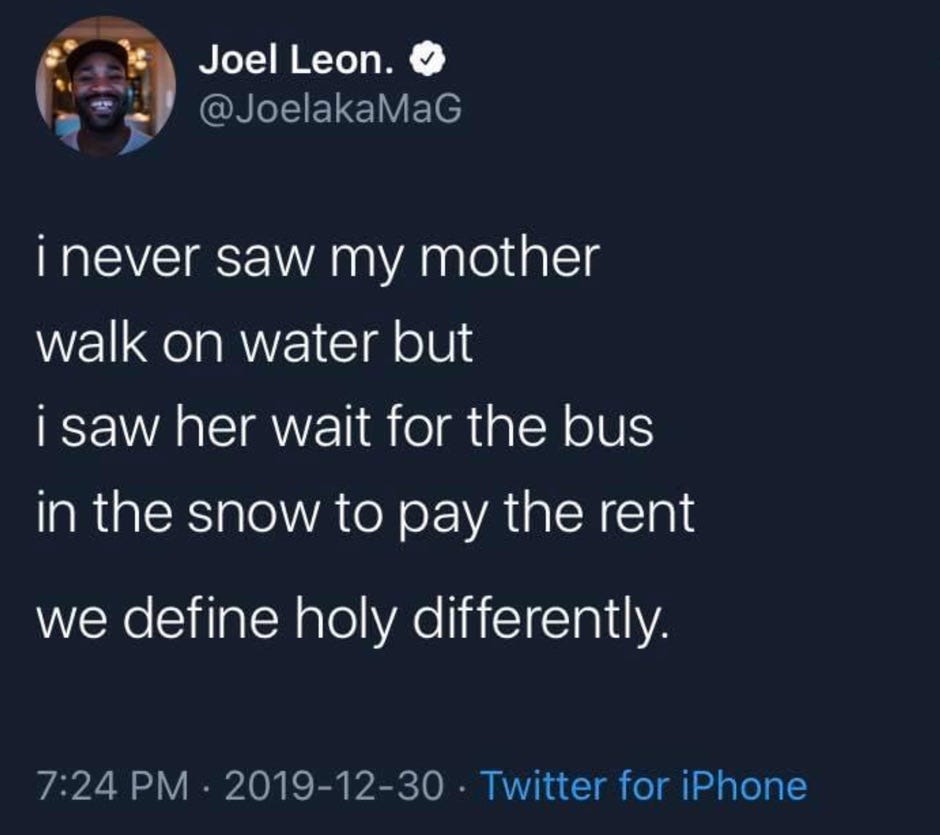

I read these things about trees and I think about the life my own mother gave me, what sacrifices she made and still makes. I think about how when I was growing up, she was parent-in-absentia to the rest of the neighborhood kids, ready with lunch or a hug or homework help for the rest of them, who so often went without those things. I think about the years of hell we gave her anyway, because to be a teenager is to be kind of an asshole no matter how loved you are. I think about the innumerable little sacrifices my mom and dad made, that my brother and my sister-in-law make for their kids, that my friends who have children do for theirs, and I am moved beyond words.

I am no longer a Christian but I can’t help but think of parenting in whatever form we receive it as a Christlike sacrifice. How many of us—people, trees, or otherwise—are where we are because the people who raised us gave up the bodies and souls they previously knew for us? To be nurtured, cared for, cared about is a holy thing.

The sacrifice is incalculable, even if no debt is claimed.

Scientist Hope Jahren writes in her memoir Lab Girl that

There are botany textbooks that contain pages and pages of growth curves, but it is always the lazy-S-shaped ones that confuse my students the most. Why would a plant decrease in mass just when it is nearing its plateau of maximum productivity? I remind them that this shrinking has proved to be a signal of reproduction. As the green plants reach maturity, some of their nutrients are pulled back and repurposed toward flowers and seeds. Production of the new generation comes at a significant cost to the parent, and you can see it in a cornfield, even from a great distance.

There’s a song about all this by Jason Isbell called “Children of Children” that gets me emotional every time I listen.

You and I were almost nothing

Pray to God the gods were bluffing

Seventeen ain't old enough to reason with the pain

How could we expect the two to stay in love

When neither knew the meaning

Of the difference between sacred and profaneI was riding on my mother's hip

She was shorter than the corn

All the years I took from her

Just by being born

The closer I look the more apparent it becomes to me that the forest has a heart and soul, one mirrored in our own. One capable of giving, sacrificing, sharing.

It also becomes apparent that, like us, the forest has a brain. Or perhaps more accurately is a brain, a dense and ineffable tangle of living cells entwined by synapses of roots and fungus, constantly sharing not just resources but information. If we allow that trees in a forest are capable of giving with intention, then it stands to reason that the forest must possess an organ capable of having intentions.

Trees use their mychorrhizal networks, those mazelike miles of fungal thread, to demonstrate those intentions. Introduce a tree-killing beetle to a stand of firs, and the firs will flood their fungal network with warning chemicals, triggering a release of beetle-killing chemicals from their Ponderosa pine neighbors. Many deciduous trees, when their leaves are being chewed by animals or bugs, send airborne chemical signals to neighbors, telling them to ramp up their own volatile organic compounds to deter further attacks. Birch trees fix nitrogen to help firs grow tall and strong, firs which then pump sugars back to the birches in the winter to keep them alive.

What would it mean to our own understanding of life, of consciousness, of care to accept as true that other organisms have developed their own methods of doing just that? What would it mean for our future, if we stopped seeing nature as a beautiful accident and began to see it as another form of sentience, one both entirely alien to and necessary for our own?

Hope Jahren continues:

The leaves of the world comprise countless billion elaborations of a single, simple machine designed for one job only – a job upon which hinges humankind. Leaves make sugar. Plants are the only things in the universe that can make sugar out of nonliving inorganic matter. All the sugar that you have ever eaten was first made within a leaf. Without a constant supply of glucose to your brain, you will die. Period. Under duress, your liver can make glucose out of protein or fat – but that protein or fat was originally constructed from a plant sugar within some other animal. It’s inescapable: at this very moment, within the synapses of your brain, leaves are fueling thoughts of leaves.

Of course, it’s possible that my inescapably human framing—conceiving of a heart, a soul, a mind—also misses (ahem) the forest for the trees. Perhaps in the end the forest defies analogy because it is truly unlike anything that the brains of primates much younger than itself could ever hope to really understand.

In his best-selling The Overstory, Richard Powers describes this unknowability:

The motionless trees are migrating—immortal stands of aspen retreating before the latest two-mile-thick glaciers, then following them back north again. Life will not answer to reason. And meaning is too young a thing to have much power over it. All the drama of the world is gathering underground—massed symphonic choruses that Patricia means to hear before she dies.

…real joy consists of knowing that human wisdom counts less than the shimmer of beeches in a breeze. As certain as weather coming from the west, the things people know for sure will change. There is no knowing for a fact. The only dependable things are humility and looking.

How, then, do we proceed through a world too vast for us to comprehend? Is it possible for us to humble ourselves enough to admit how little, in the grand scheme of things, we really understand? I maintain that is not only our job to ask these questions, it is our job to pass them along to those who will come after us.

If there is a reason to keep going, it is this. If there is a reason to take up the thankless slog of self-sacrifice that is required to take real care of others, it is this. We are all bound together—by blood, by water, by earth, by fungus—and it is only because we are so bound that we are able to do anything at all. It’s true that in the grand scheme of things that we understand very little. But we understand enough to know that there is no way forward but to care for one another.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be. (That said, if you’d like to support this newsletter monetarily, there’s now a voluntary paid subscription option too. Just click whichever option you’d like.)

Share this post