If you, like me, are the kind of person who spends any time on Twitter, you have probably not escaped seeing at least a few cryptic posts containing nothing but the word “Wordle,” a number, a fraction, and a grid of colored squares.

These are the product of a new-ish game called—you guessed it—Wordle, which has taken the internet by storm over the past few weeks.

For the uninitiated, the basic premise is that you have six tries to guess the day’s five-letter word. The game will color-code your letters to tell you whether they are in the right place, in the word but in the wrong place, or not in the word at all. (Hence the map of colored squares.)

It’s a relatively simple concept that is just challenging enough to make playing feel like something worth spending time on. Being able to auto-share your scores in a format that all other players understand, and judge yourself and others accordingly, is also a big part of the draw. If they take more words than you to get it, you can mark them as the rubes and simpletons that they are. And if they get it in fewer tries than you, well—everyone gets lucky once in a while.

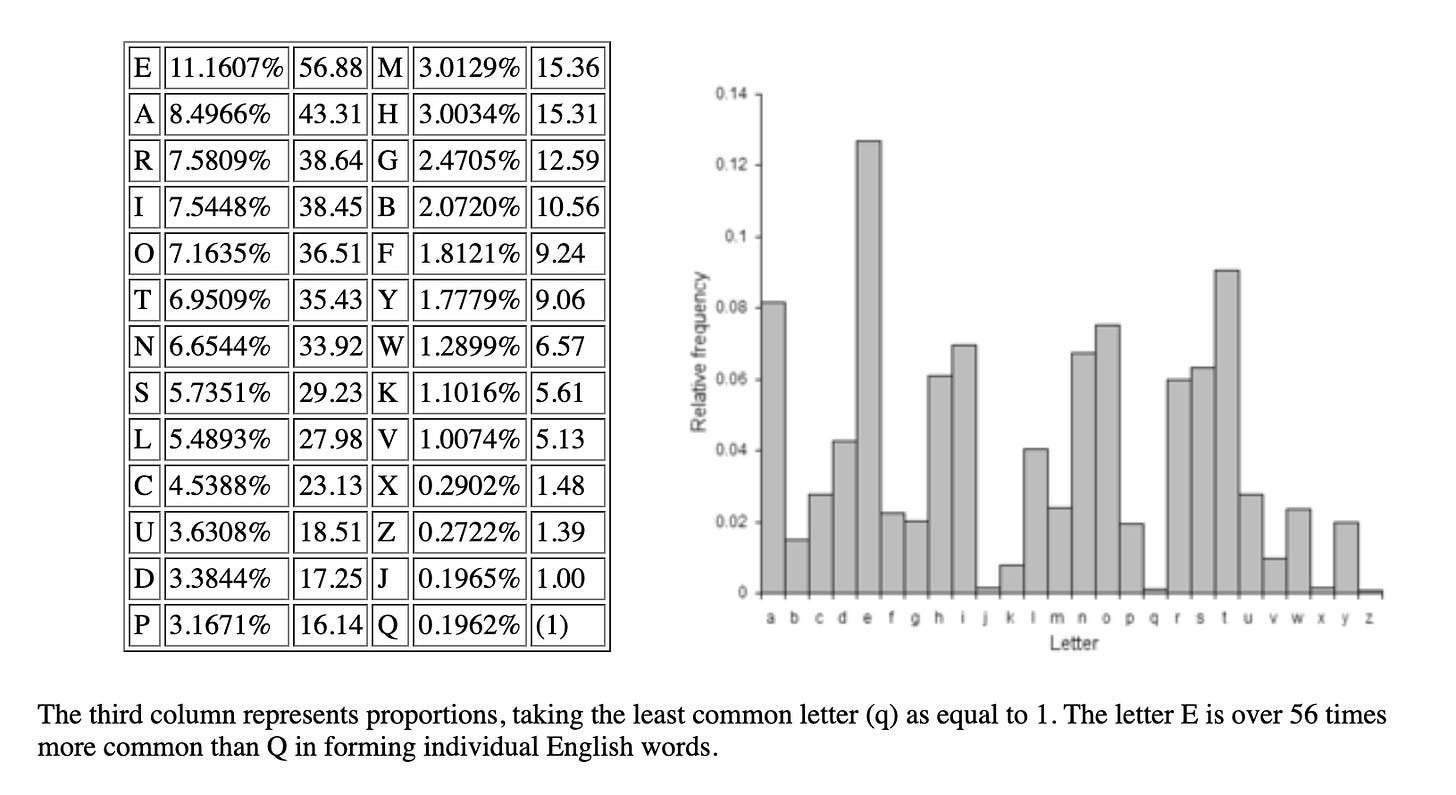

One of the tenets that underpins the game is an understanding of English letter frequency, which you probably have at least a passing grasp of if you’ve ever watched Wheel of Fortune or played a round of Scrabble.

Something I love about the game is that there are still uncountable different first words that might emerge from this basic understanding. It might make perfect sense to some people to stack all the most common letters and aim for TRAIN or REINS or something similar; for others, you might try to play Moneyball and mix a few less- common letters in, knowing that it’s often easier to identify an entire word based on the unique placement of a G or K than that of a T or S.

I first got interested in concepts like letter frequency in college, where I spent my first two years as a Linguistics major.1 One of the electives I took to satisfy the requirements was called “Code Making and Codebreaking.” The class was taught by a grad student named DJ, a former priest who had lived in Russia for nine years and was fluent in several languages.2 He structured the course such that the entire curriculum was one giant group project. We had frantically picked 3-5 partners on day one, and every assignment for the next ten weeks—including our final, which entailed devising our own cipher and assigning it to another group to break, and vice versa—was done as part of that team. One of those teammates is still a friend of mine. This creative, collaborative method of instruction dramatically changed my own perspective on teaching, and still influences my own curriculum planning to this day. It was the best class I took in four years of college.

Besides the mechanics of code making and codebreaking, we also learned the history of the codes we were playing with. We learned about how Mary, Queen of Scots met her grisly end because her plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I was enciphered in too amateur a fashion. We learned about the purportedly unbreakable Vigenère cipher used by the Confederacy, which the Union repeatedly broke to turn the tide at key points of the American Civil War. And we learned about the Playfair cipher, which changed the course of American history when a wounded John F. Kennedy used it to call in the location of his surviving crew in remarkable fashion after their PT boat sank:

…eventually Melanesian natives came to the aid of the eleven Americans. The natives carried Kennedy’s SOS message, scratched on a coconut shell, to an Australian Navy coastwatcher, Reg Evans, who was working behind enemy lines. Evans radioed the U.S. Navy for assistance.

Kennedy had a bad back, and still towed a badly-burned crewmate the long distance to shore by towing a rope between his teeth as he swam. His own wounds didn’t stop him from attempting several abortive swims to find rescuers. While the Playfair cipher (and more importantly, the Solomon Islanders who found him) eventually aided in his rescue, the death and destruction he witnessed as a soldier during those hellish days stayed with the future president for the rest of his life. That anecdote and others are related in James W. Douglas’ JFK and the Unspeakable, a sober and rigorous bit of scholarship that proves—beyond a shadow of a doubt, in my mind—that the CIA killed Kennedy. Why?

From the lives he had seen lost in World War II, Kennedy had envisioned in 1945 ‘the day of the conscientious objector,’ with an international relinquishing of sovereignty and the abolition of war by popular demand…[as President during the Cold War] he therefore had no way out except to negotiate a just peace with the enemy…He would learn just how dangerous it was, from his own side of the conflict, to push through such negotiations.

Douglas makes the case that the horrifying lessons JFK learned as a soldier were the first step in his transformation from warrior to would-be architect of peace. There were simply too many powerful people invested in the perpetuity of the Cold War to allow that to happen, especially once Kennedy—through backdoor communication channels with our nuclear rivals—had begun to see Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro, and the people of Russia and Cuba, as, well, human.

That’s a full story that’s better told in Douglas’s book than in this measly newsletter. For now, let us be satisfied with the bizarre truth that the linguistic principles undergirding the internet’s game du jour are the very same ones that saved the life of a future president and paved the way for one of the greatest public tragedies in American history.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be.

I abandoned ship after a disastrous attempt at a high-level Phonology class at the end of sophomore year, when I realized I was better suited to the comforts of English literature.

We learned this at the end of our first day of class, when, after speaking with a heavy Russian accent for the better part of two hours, he switched into his normal Indiana accent and let us know his whole backstory.