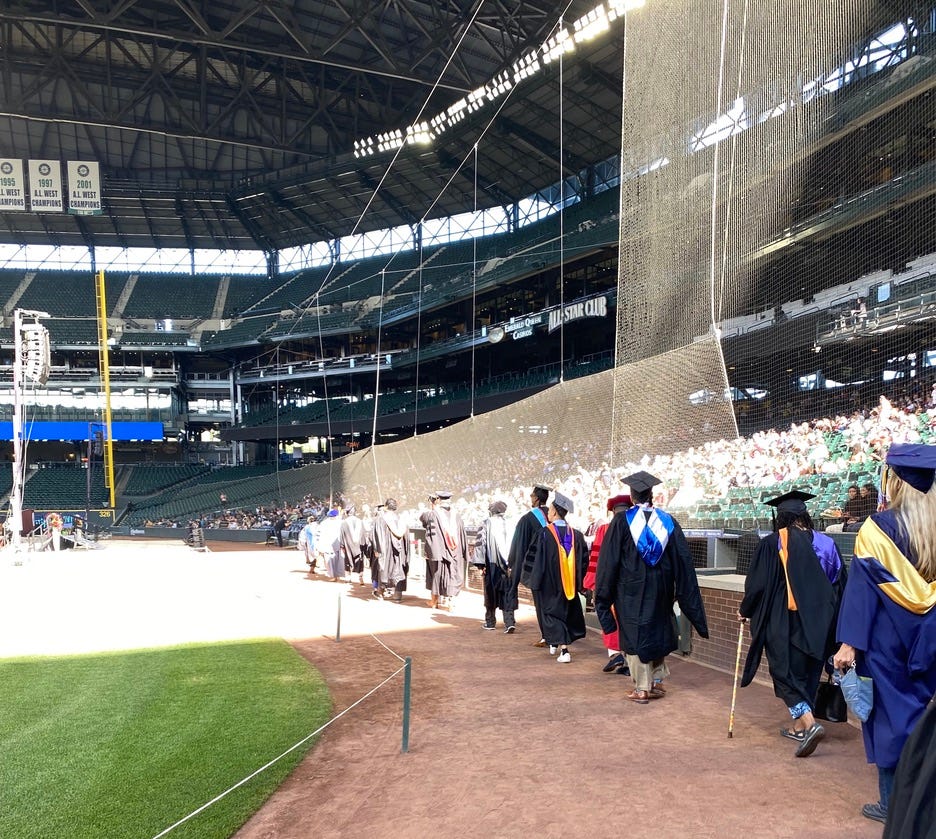

Last night I watched as a handful of my students walked across the stage at the Seattle Colleges’ joint graduation ceremony.

Some of these students I have gotten to know well over the years, working (and occasionally bickering) with them from the start of their GED journey til the end. Others I have known only as black boxes and white names on a silent Zoom screen, maybe getting a quick look at their faces on their first day before they realize they don’t want to be the only person (besides the corny older guy) with their camera on. Strange seeing these students walk and move in three dimensions, with a height and depth and humanity that doesn’t come through when education is mediated through a computer. Still others I have known and seen in person, but only from the bridge of the nose up and the neck down. Such is life in a masked world. This, too, makes for a bizarre experience. (One of my longtime students said hi as I walked past the line and it took me a minute to place her—I’d never seen her mouth move before.)

Regardless of how I’ve known them, they were to a person more dressed up and put together and awake than I’d ever seen them before. And it made my heart ache to see them like that, these people in the tangled wilderness between childhood and adulthood, many of them being recognized as special and accomplished for the first time in their lives.

My first thought, as the solstice afternoon sun poured over them on that stage, was that I’d like to trap this moment in amber for them, to hold it fast forever before they could step off the other side back into a city and a world that is not likely to be kind to them. They are no strangers to this idea; students typically enter our program lacking some academic skills but rarely are they naive about the horrors and injustices of the present day. When students open up to me—usually through their writing—it’s often a window into the trajectory that took them from the delivery room to my classroom. For plenty of them, it’s been a cavalcade of hardship and suffering beyond my imagining. Knowing this made me want to preserve them in that golden moment all the more.

Of course if we stay frozen in time things can’t get worse, but that also means they’ll never get better, either. So I don’t really want to encase that evening in amber. Molasses, maybe. Slow things down a little.

It struck me that the student speakers, one from each of the three colleges in our district, focused not on the bright figures which are so often the theme of these kinds of speeches, but on the past—the two-plus years of struggle and hardship that led to this first in-person commencement since 2019—and on the present, the new bonds of solidarity and kinship they’re carrying with them. Is it like that elsewhere, too? Or are they still pretending elsewhere that the future is as bright as it’s ever been? I used to want to be the kind of teacher who would get invited to speak at graduation, and I think I still do, in the abstract, though I worry I would do plenty of pleading and little inspiring. Love people well and figure out what you’re willing to fight for is maybe all I’d have to say.

Despite the tonal shift from other commencement ceremonies I have attended1 it was far from a grim affair. Graduates had still decked themselves out in their best celebratory accessories, had still decorated their mortarboards to reflect their personalities.2 Families still hooted and hollered and blasted noisemakers and clogged the aisles to the chagrin of ushers trying to keep grads lined up. Crusty administrators bewildered by the parade of dyed hair and cleavage and piercings and queerness still grinned their way through diploma handoff photos with students who probably didn’t know just how much harder those particular administrators had made their educational experience. Students who had never spoken to each other before and likely never will again chatted as warmly and intimately as old friends, swept up in the good cheer.

It is this, more than anything, that continues to give me hope. That people who have been dealt terrible hands will still dream and strive and accomplish things in the face of the odds, and that the people who love them will honor them for it. That we will find reason to come together, to carry out our rituals, to celebrate until we’re hoarse, even as the fabric of the world we know frays and tears. Whoever first said that life is a shipwreck but we must remember to sing in the lifeboats3 was pretty astute.

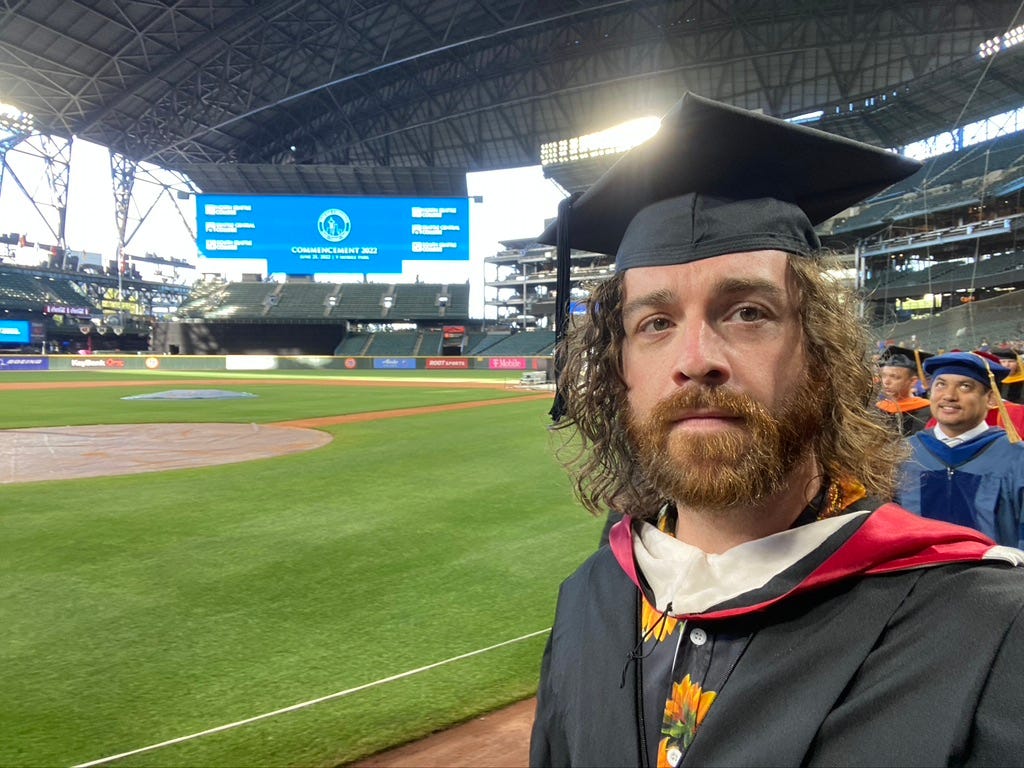

As I mentioned in this newsletter a few months ago, my wife and I are leaving Seattle for Detroit later this summer. So not only was this ceremony the end of some of my students’ tenure at our college, it also felt like the end of my own. I am teaching summer classes, as I have done every year, but outside the cycle of the normal school calendar things don’t feel the same, and my enrollment numbers are usually paltry; for all intents and purposes my regular classroom experience is over. And I will carry plenty with me from my six years in this district, but this last memory might also be the sweetest.

That I should find such golden afternoons in whatever comes next.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

The last time I went to Seattle Colleges’ commencement, in 2019, I went to bed early because I had to wake up the next morning to go canvass for Medicare for All. The juxtaposition between the world I lived in then and the world I live in now is frankly staggering.

These ran the gamut from “WITH GREAT POWER COMES GREAT RESPONSIBILITY” (on a Spiderman-patterned background) to “ALL CREDIT GOES TO ALLAH” to “EDUCATION IS A SCAM.”

It wasn’t Voltaire, although he is apocryphally credited.