I went backpacking with a few friends this past weekend. Up the West Fork of the Foss River, climbing steadily higher past a succession of lakes that pour into it and one another. To our destination at Little Heart Lake it was some 5.5 miles from the trailhead, a distance to sneeze at for 2016 me (who I find I can’t stop comparing myself to anytime I set out on a hike) but a hard few hours here in the hard year of 2020. The trail climbs more than 2,500 feet in that distance, crossing from a gentle fragrant forest of cedar and Douglas fir into exposed and brushy switchbacks that flirt with the river for two miles without letting one get close enough to drink from it.

From over the lip of an ancient cliff a pair of twin braided waterfalls cascades, joining the lakes above and the river below. Just above is Copper Lake, a glacial basin of impossible blue fed by countless more waterfalls of summer snowmelt. A few hours of sweat and toil brought us up and over that lip and back into the wooded plain of lakes above. Words can’t do it justice.

Amidst the relentless sun and the mosquitos and the burning in my thighs and calves was a lifting of a weight I hadn’t realized I’d been carrying. What I felt was an absence of feeling suffocated, I think. This pandemic and the ensuing isolation have robbed us all of a great many things (and robbed too many people of everything). One of those things is surely the automatic sense that other people are basically an okay feature of the world. Now everyone is to be suspected, judged, avoided; when the enemy is invisible, the enemy could be anyone, and that’s a terrifying reality we’ve all been living with for months now. An endless stretch of days wasted without being able to be nonchalant about anything, anyone.

I’ve found that feeling reflected in this song I can’t stop listening to, Billy Strings’ “Away From the Mire.”

Spring lied to us this year again

I can't stand to face the fear again

But you could always laugh about those things

It's enough to make a man feel sour

Burning minutes every day by the hour

Just to end up gone like everything else

(It’s a long song but it might be worth watching the video instead of just hearing the Spotify version to get a sense of the jaw-dropping picking speed happening here. The facial expressions aren’t bad either.)

In these lyrics—which, as the protagonist of reality, I have a hard time believing were written by someone a few years younger than me—is also permission to feel those things deeply and honestly.

Let go of the pain and hold onto the rhythm

It's consciously held back in you

Drowning a sorrow that's long been at rest

The past is a hell, it can creep up inside you

So let me remind you of this

It's the reason your troubles exist

Relatedly: Something that struck me as we alternated between bustling around to cook and lounging around the campsite was how much I have missed the social aspect of food during the past four months. My group of friends, in the Times Before, cooked at least one meal together every month—and most months it was more like three or four. One of the subtle joys of adulthood that I had not prepared for was that which comes from the synthesis of goofing around and working hard in the kitchen. The way that you can combine amateurish experimentation and professional concentration to feed a room full of people and be happy and worn out and fulfilled before you’ve actually taken a bite.

The Michelin-starred chef Francis Mallmann discusses this phenomenon in his episode of Chef’s Table. Rare is the shot in which Mallmann is preparing food on his own, the solitary genius at work. Instead it’s more like the most focused party you could ever hope to attend.

When we have big parties outside, I like to have a big staff…What we have is what is called in Spanish maestranza, which means getting help from those around you. It’s a very beautiful word, it’s very romantic. I don't like to accept chefs with experience. We accept young apprentices in all our restaurants that have never cooked elsewhere and we teach them.

That spirit, that maestranza, has been at work in my friend group for five or more years. It’s there in our regular Friday get-togethers, where the best chef among us, Trey, supplies scratch pizza doughs and a groaning table of toppings for us to combine and perfect. It’s there in the attempts we’ve made at, among other things, roasting an entire duck. (We learned that you’re going to have to crank the oven to 500 degrees to make that happen.) It was there the time we had to evacuate an apartment after some Chiles de árbol got left in hot oil for a minute too long on their way to becoming a salsa.

We haven’t had that now for four months. (The duck incident was one of the last things that happened before the world shut down in March.) So to be able to even come close to approximating that—dumping potpurri flakes of dehydrated bison chili into pots of boiling water over tiny flames—meant a whole lot to me. There were the occasional reminders of what plagued the world outside, like the way we’d slide our Buffs over our faces when we passed other hikers or how I had to sleep alone instead of cozying up with a friend. But for longer stretches than I thought possible, we got to forget.

Mallmann, in the clip below, also talks about one of the reasons for cultivating that maestranza in the first place.

Today I think we educate kids to be settled in the comfortable chair. You have your job, your little car, you have a place to sleep, and the dreams are dead. You don’t grow on a secure path. All of us should conquer something in life—and it needs a lot of work…In order to grow, you have to be there, a bit, at the edge of uncertainty.

You’ll notice he’s able to square a statement that on its face seems to be about pure individualism with the fact that he thinks the best work is done as part of a team. I share the sentiment that such a thing can and should be cultivated as part of a collective effort, which will probably not surprise you to hear.

On Saturday evening we beat a hasty retreat to our tents to escape the swarms of mosquitoes, who took advantage of our being camped above the fire line and made a feast of our legs and necks. Trey had brought along a printed copy of Outside Online’s report on the memorial dinner that the author Jim Harrison’s friends threw after his passing. Harrison, like Trey, was a world-class gourmand and a Michigander; in tribute to both of them (for my friend is moving back to his home state in a few painfully short weeks), I read it aloud in the gathering dusk. The author of the piece recalls something Harrison might have said:

Don’t be such a fascist—have some sweets.

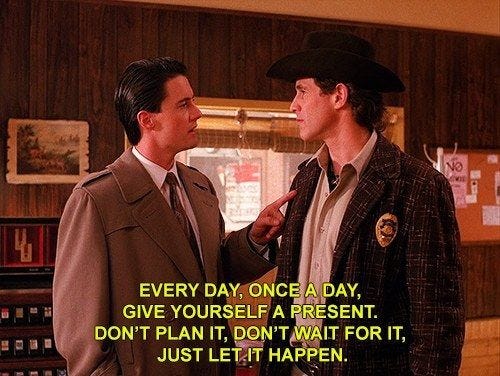

Harrison has something in common with Special Agent Dale Cooper in that view. I think I have mentioned in here before that I’m a huge fan of Twin Peaks—its quirks, its charm, its willingness to look steadfastly into the face of evil and depravity without losing its essential moral center. I’ve only seen 2017’s Twin Peaks: The Return once all the way through, but I liked it, too, after I had some time to digest it. I was recently reading a series of essays on The Return by Nick Pinkerton (no small feat for someone like me, who finds most TV and film criticism totally inscrutable) and was struck by a passage from the third one. It reads:

The first time that I encountered the image of Dougie in his signature lime-green blazer standing in the plaza outside of the Lucky 7 insurance agency in Las Vegas and staring up rapt at a bronze statue of a slender male figure wearing something like a ranger’s hat and taking deadeye aim with a pistol, I remember thinking that this right here was so far from anything that I expected to encounter in a rebooted Twin Peaks—and an image of uncommon emotional resonance at that, keening for the loss of an unnamed something, something to do with the distance we’ve come from the fresh and untrammeled outdoors, perhaps, or with a sense of duty, a feeling of ramrod-straight forthrightness and heroic possibility.

I feel like that last sentence just X-rayed my chest.

I’ll leave it there for this week. As always, if you want to support this newsletter, please feel free to subscribe so you don’t have to go hunting for it in the future. If you already subscribe, why not pass it along to someone else who might like it? And if you’re one of those people worried about the distance we’ve come from the fresh and untrammeled outdoors, you might like my book about the time I closed that distance.

Take care—I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck