Tabs Open #11: It Wants The Earth And The Fullness Thereof

Fireweed is so called because in the mountainous places of this country it’s often the first thing to grow after a blaze devours a section of forest. It’s a beautiful plant made all the more so where it rises in contrast to the gray rocks and the skeletal remains of the trees that stayed standing even as they burned.

Strange, that: to thrive in the wake of cataclysm. To grow in such conditions, with such color—an obscenity.

Or perhaps not. Perhaps it’s just the opposite, a defiant flag raised to show the world that things will never stop growing.

What does it mean to be alive, a person—today, this year, any year? I suspect most of us spend the duration of that time alive not knowing for sure. What do we owe to ourselves, to each other, to anything that breathes or grows or flowers?

There is, paradoxically, a comfort in not knowing what all this is for, because if none of us do, then all we can do is lean on each other to find out. It’s like I tell my math students when I group them up to work on a particularly thorny problem: sure, you don’t know now, but if you take a moment to stop and think together, who knows what you might come up with.

I’m concerning myself with the idea of just that—the self, and what to do with it and with everyone else— because it seems as though everything I’ve read this week confronts that question in some way or another, internally or externally. In one way or another they all wonder what it means to live (to dare to thrive, even) in a world that has burned in so many ways already.

1. I want to start this week’s list with a long piece that I paused about 14 different times to think about before continuing on. Titled “How to Do Nothing,” it’s a transcript of a talk by Jenny Odell that formed the thesis of the book of the same name she recently published. (If you’re not the reading type, you can watch the talk here.)

The talk itself is great, but the transcript holds up by itself. It has a casual, lyrical tone, and the subject matter meanders, like the labyrinths and pathways that Odell herself is so concerned with. She ties together such disparate concepts as birdwatching, the labor movement, rose gardens, Deep Listening, and contemporary architecture with the thesis that it is an intentional, meaningful act to do nothing. (Like with all other things she addresses, what she means by Doing Nothing is slightly more complex than it might appear on the surface.)

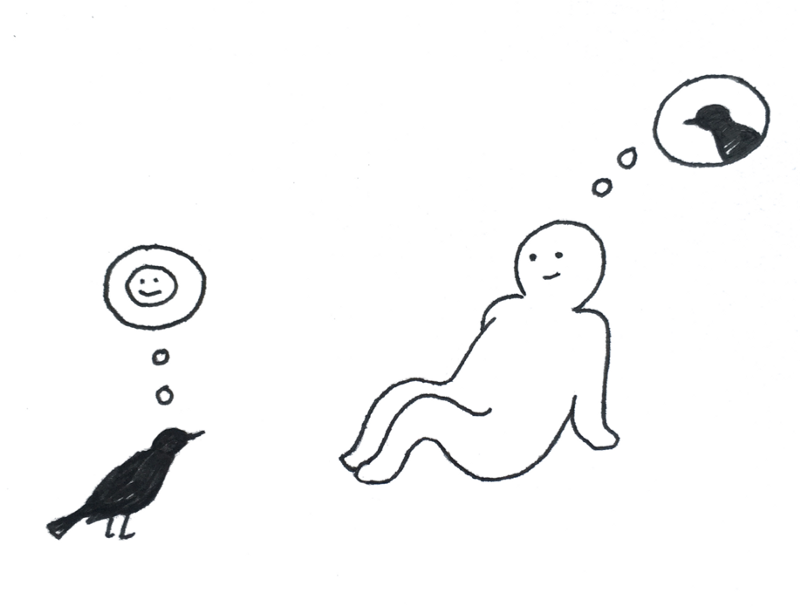

This doing nothing is at once an internal act of self-preservation and an external opening of oneself to the world in all its peculiar filigree. It is also a feedback system: “…perhaps the granularity of attention we achieve outward also extends inward, so that as the perceptual details of our environment unfold in surprising ways, so too do our own intricacies and contradictions,” as Odell so eloquently puts it.

Spend an hour (and it will be spent, in the way that Annie Dillard meant) with this talk and the accompanying drawings and videos and contemplate what Doing Nothing might do for you.

(Odell drew this, somehow knowing exactly what’s playing inside my brain like 70% of the time.)

2. It’s important to cite one’s sources. I found the aforementioned talk linked at the end of another newsletter that I signed up for recently, L.M. Sacasas’ “The Convivial Society.” Sacasas is the director of something called the Center for the Study of Ethics and Technology, which sounds like it should be a think tank that the Koch Brothers and Jeff Bezos jointly fund so that people will write policy papers about how it’s actually good for the economy to turn the poorest 1/4 of Americans into a nutrient slurry to be fed intravenously to Amazon warehouse employees to keep them upright during their 18-hour Prime Shift™️. It’s not that. Sacasas and the folks at CSET investigate the moral issues surrounding technological growth and development through a theological lens.

I’m too stupid to do any of that kind of thing myself, so I’m glad he has a newsletter, is what I’m getting at. The most recent issue dives into what it means to be alone, and how people’s reactions to being alone—the sustained kind of alone, not just fleeting loneliness—can have serious implications for the world. Hannah Arendt, Sacasas reminds us, “went so far as to find in pervasive loneliness the seedbed of totalitarianism.” That a generation of white American terrorists fit this bill is probably no accident.

The rest of the newsletter deals, quite deftly I think, with the notion that our online emphasis on “finding one’s people” doesn’t serve us as well as we think, because it makes the real world seem that much more abrasive and inconceivable. Later he explores the differences in what we get out of our “groups of affinity” compared to our “groups of necessity.” A point he makes that is worth considering in the larger context his piece creates: “We may take our proper joy in finding our people, but we will need to figure out again how to live, so far as we are able, with those who are not.”

3. To narrow the focus a bit as we continue to explore these musings on what it means to in the world, we’ll turn from what it takes to live with everyone and think about what it means to live with just one other person, forever. The writer Jim Harrison, the kind of historical figure who’s often described euphemistically as having “tremendous appetites,” died in 2016, just months after his wife of half a century, Linda. During his career Harrison concerned himself with both the large (the distance between stars, the unfairness of America’s bloodstained Manifest Destiny) and the small (the temperature of rivers, the droppings of animals in the forest). Through all his writing runs not just a deep lust for life but a love for it, a noticing of things that Jenny Odell would surely appreciate.

Dean Kuipers reviewed Harrison’s posthumous book of poems for LitHub last week and eulogized his friend, the poet himself, all in one go. Despite his one good roving eye, Kuipers tells us, it was Harrison’s love for Linda that kept him going, and the absence of her that finally stopped him. It’s a rare book review that’s written as movingly and impressively as the subject it hopes to cover; Kuipers passes muster here. Even if you’ve never read Harrison, you’d do well to read this final examination of his work.

4. Harrison, fittingly enough for our next tale, served as the opening and closing act for the episode of Anthony Bourdain’s “Parts Unknown” that explored the culinary and cultural life of Montana. I adore the show and find it endlessly rewatchable; it’s curious and sensitive rather than voyeuristic in the way that travel programs tend to be.

Bourdain’s commitment to getting the story right by letting other people tell it was highlighted this week in a retrospective on his trip to Appalachia. His humanizing approach forms a stark contrast to the exploitative one taken by Hillbilly Elegy’s J.D. Vance, whose book blames the poverty of the region largely on individual and cultural issues, framed by a narrative of personal responsibility and hard work. That this obvious mischaracterization of what truly ails the region—the forces of capital sucking it dry over a century and a half—is put on blast in CNN, of all places, is pretty astonishing.

5. Speaking of Appalachia: the deck seems pretty stacked against people hoping to transform the systems by which we power the country, huh? The oil and gas and coal companies aren’t going to give up their stranglehold on the world anytime soon, and we can’t seem to agree on much politically in this country, much less a wholesale overhauling of the global economy.

So what cause is there for hope, or even action? What could possibly make it worthwhile to subordinate the self to the greater movement to quite literally save the world? Maybe the question itself makes the answer self-evident. But just in case, I found this piece, “Plan, Mood, Battlefield - Reflections on the Green New Deal” a worthwhile examination of the point. It explores in depth the inevitable failures of multiple proposed pathways—both the keep-capital-intact incremental solutioneering of the Democrats and the revolution-now-or-else posturing of the disorganized anarchist Left. It’s a stiff challenge we’re all up against; identifying the dimensions of the battlefield is a necessary first step in fighting it.

6. I’m a little worried that I’m using up too many great pieces in one newsletter and that I’ll have nothing to say next week. But they all follow the theme here so beautifully that I’d be remiss to leave any of them out.

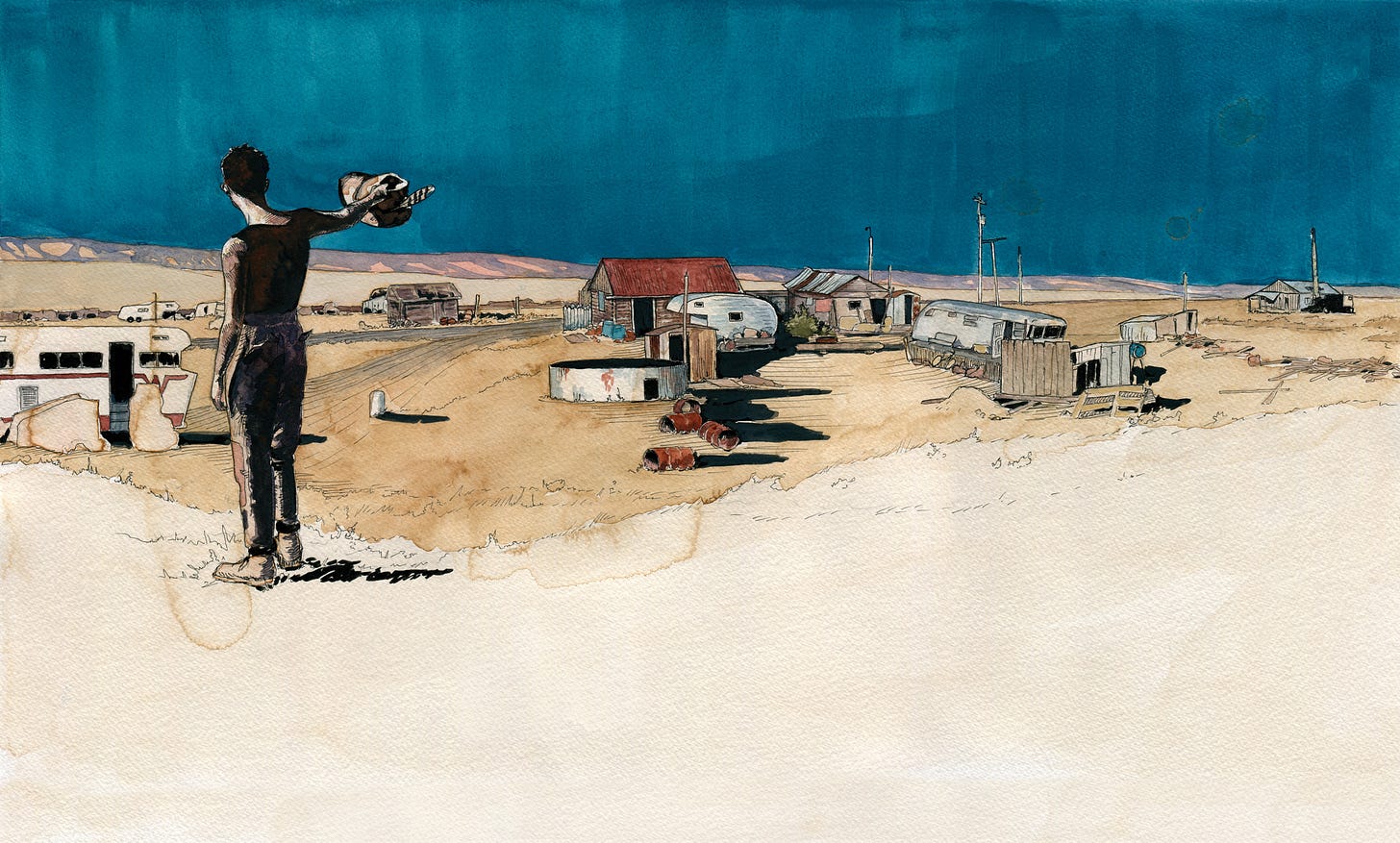

I was captivated by this essay from High Country News about the alleged ghost town of Cisco, Utah, where it turns out people actually still live. Eileen Muza, the woman whose life story forms the backbone of the piece, is a fascinating character. And like all other things we’ve covered this week, what on the surface appears to be a tale of hardscrabble individualism is actually something much richer: a mapping of the interconnectedness and community required to scrape out a living in a place that the country has largely left behind.

(Sarah Gilman, the author of the piece, also illustrated it with beautiful pieces like this.)

7. Okay, enough reading for this week. Here’s Glenn Campbell to play you out.

Thanks for reading! If you liked what you read this week, please feel free to subscribe and pass the newsletter on to a friend. (If you didn’t like it, feel free to pass it along to an enemy.)

-Chuck