Tabs Open #14: Less Erroneous Pictures of Whales

The first Democratic primary debates happened last week, you may have heard. When you cut through the usual horse race horseshit I think they’re useful exercises, in the sense that they help us figure out how we’re going to answer two important questions: what kind of country are we going to be, and how are we reckoning with the idea that the decisions we make today will have massive effects 20, 30, 40 years down the line?

If you’ve ever read this newsletter before it will come as no surprise to you that I often turn to fiction to help myself navigate such thorny questions. More often than not this leads to more additional questions than it does answers, but what better do we have to do than to work on these existential quandaries, I ask you.

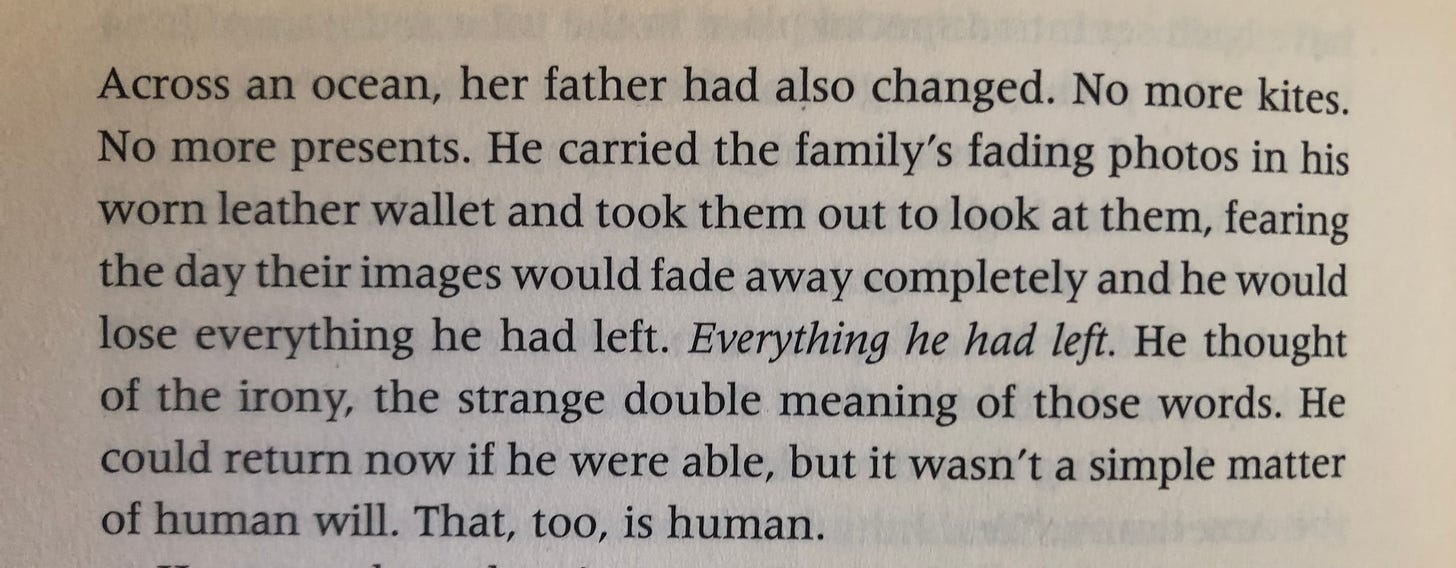

A book that addresses those two questions I mentioned above better than most is Linda Hogan’s People of the Whale. Hogan is a Chickasaw poet, playwright, environmentalist, and academic, and her novel—the Great American Novel, if you want my opinion—grapples with the far-reaching effects that the Vietnam War has on a small indigenous American community, even decades after its end.

Stories like this are important not just because it’s important to know our country’s history, the mindless cruelty our tribes have been subjected to and the pointless horrors of Vietnam, horrors that lived on long after the war’s end, but because that history is being relived again today. We’ve been at war in the Middle East since a few weeks before my 11th birthday; I’m a few months shy of 29 now. I’m not the first to point out that the war in Afghanistan is almost legally old enough to fight in the war in Afghanistan.

So it is that I always watch these things with a mixture of trepidation and hope. Sort of like how it feels to start a book that you don’t know much about, like maybe all you’ve heard about it was a brief recommendation in a newsletter you were skimming.

Anyway, it’s a hell of a novel and I think you should read it. And despite its occasional forays into small magic (or at least an eye open toward deeper possibilities than what we are accustomed to), it is not even particularly fictional in scope: a key section of the novel centers on a teenage boy’s efforts to lead a successful whale hunt to feed his people and restore their pride and their traditions. Though the novel was published in 2008, these same concerns continue to face indigenous communities today—take Chris Apassingok, who in 2017 at the age of 16 successfully killed a bowhead whale for those same reasons listed above. When the story broke, he and his family were exposed to the worst the Internet has to offer, death threats and more. Our views of what it means to take a life and what kinds can be taken and why are so narrow and cruel.

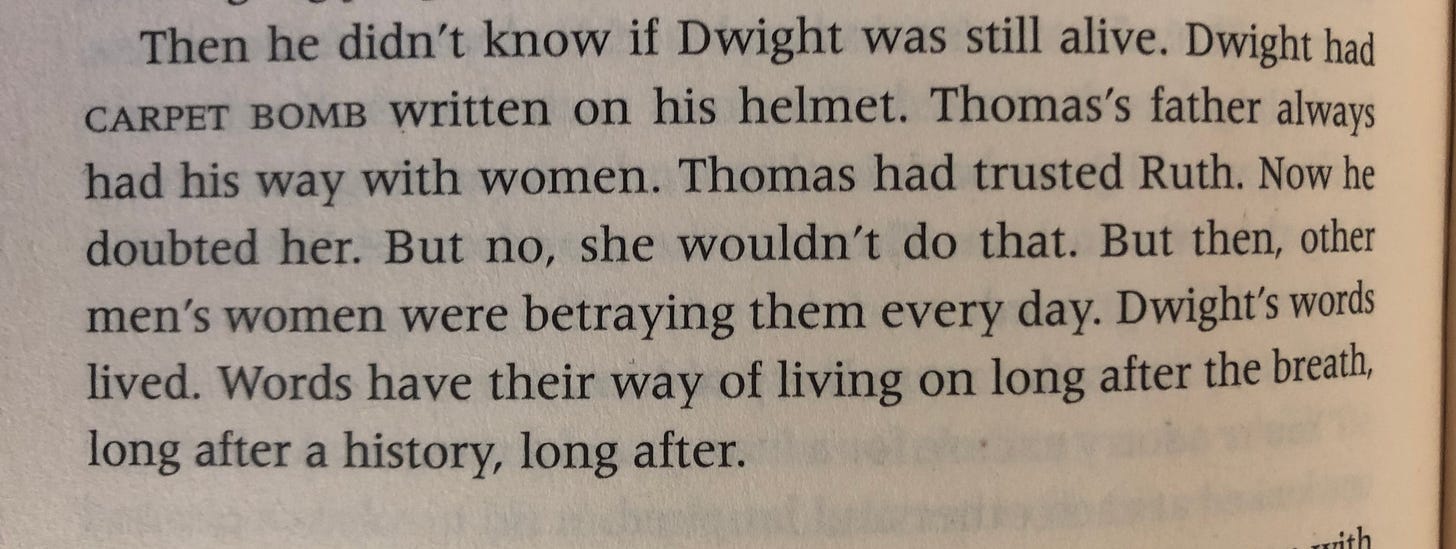

There is of course also a component of all this that is wrapped up in the language we use: what we remember and what we conclude about those memories is tied intimately to the words we use to describe them in the first place. The language of war is the language of dehumanization and obfuscation; otherwise how could the public ever get behind it? And the language of memory is just as malleable:

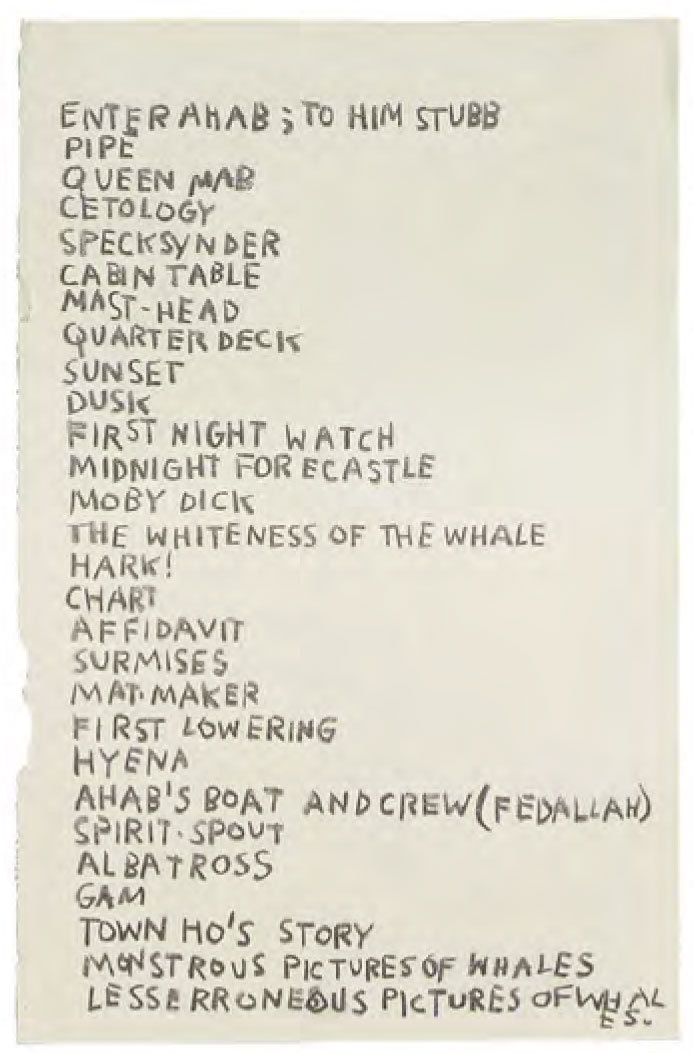

It is of course difficult to talk about novels and whaling without talking about what is (fittingly) the leviathan among them: Moby-Dick, which when read through a certain lens becomes essentially the story of a person who suspects he might be depressed and so seeks out the great unknown and quickly ends up over his head, and now I’m realizing as I type this that it’s possible to accidentally write yourself into a sentence.

Moby-Dick is itself a worthwhile piece of art, and it has also laid the groundwork for a lot of other cool art—a good legacy to have, as legacies go. Jean-Michel Basquiat, for example, found the table of contents alone to be compelling enough to make something from:

Ultimately what these stories of water and life and these interminable election seasons with their requisite circuses have to show us is that, for good or ill, some choices and some words will endure. It is much harder to remake the world than to allow the inertia of capitalism to unmake it, to cave to the system’s demands of accumulation and growth (almost an insulting word to use for something so destructive). The profiteers are Ahab, more than happy to take everyone down with the ship so long as they can chase something ever bigger. It is up to us to decide if we are content to live as Ishmael, chronicler of destruction, or if we want the words and deeds we leave behind to have meant something more.

We will have to make the choice carefully, for we are already tampering with the record. Ross Andersen wrote in Aeon back in 2012 that

bristlecone pines thrive in isolation. They owe their longevity to their ability to withstand the rigors of an environment that is inhospitable to their predators. If the White Mountains continue to warm, the next generation of trees will be forced to move higher in the range to find the cool temperatures and isolation they crave. Bristlecones do come equipped with an escape plan of sorts. Their seeds have long, translucent wings attached to them, and if the wind is right, they can fly long distances, pushed aloft by alpine breezes. Under ordinary circumstances the seeds could help the trees to climb up these mountains in a generation or two. But there isn’t much room to move here, because the bristlecones are already flirting with the peaks. A prolonged period of warming will leave them trapped on the summits, with nowhere to go.

Bristlecones, which can live for four or five thousand years if left to their own devices, are one of the most accurate records the world has managed to keep of its own conditions. Geology can tell us where glaciers moved and asteroids struck, archaeology can give us a picture of what used to roam the earth. But climate, weather, seasons—this data is kept best in the rings of trees.

But it turns out even time will pull the snake-and-tail thing eventually, and eat itself. Luckily we’ve got another trillion years before that becomes a real worry. Per Andersen:

Take the cosmic background radiation, the faint electromagnetic afterglow of the Big Bang. It hangs, reassuringly, in every corner of our skies…But it won’t be there forever. In a trillion years’ time it is going to slip beyond what astronomers call the cosmic light horizon, the outer edge of the observable universe. The universe’s expansion will have stretched its wavelength so wide that it will be undetectable to any observer, anywhere. Time will have erased its own beginning.

All that remains, then, is the decision, the only set of choices there has ever been: what to do with the time that is given to you.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed yourself, why not subscribe and save yourself the trouble of going looking for this newsletter again?

-Chuck