Tabs Open #25: Not Property Or Goods But The Time Of Our Lives

There’s a pair of videos that surfaced the other day that I haven’t really stopped thinking about since I saw them. They’ve seemed more and more related the more I’ve thought about them; I’d like to show them to you so we can proceed from common ground.

This could have gone so many ways other than the way it did, and I’m grateful that it didn’t.

Here’s the other:

I am moved by each of these videos for different reasons: the first for its improbable, graceful beauty, the kind found in the exhalation of a near-miss; the second for its inescapable, inexcusable tragedy. The world as it has been made creates far more of the second than the first, and if the first were to be any sort of microcosm of our reality a giant bird would have appeared and devoured the butterfly as soon as it dodged the baseball.

Then again, no bird appeared, so perhaps there is still a lesson there.

It has been a gray couple of days here in Seattle and so this dispatch is going to be unavoidably melancholy, although it will not be hopeless. I hope you’ll indulge me.

Watching that second video, as a man explains better than any politician could how incompatible something like “medical debt” is with a flourishing, decent society, I was reminded of a turn of phrase from Pablo Neruda’s “La United Fruit Co.” (emphasis mine):

it abolished free will,

gave out imperial crowns,

encouraged envy, attracted

the dictatorship of flies:

Trujillo flies, Tachos flies

Carias flies, Martinez flies,

Ubico flies, flies sticky with

submissive blood and marmalade,

“The dictatorship of flies” seems to sum up the present moment about as well as it summed up the era when CIA-backed coups and massacres interdicted the popular socialist movements in Latin America. If nothing else Neruda’s list serves as a healthy reminder that none of this—neither the generalized statistics of howling poverty and immiseration nor the specific individual tragedies like the man with Huntington’s and $130K in medical debt—is inevitable. The people responsible, as the saying goes, have names and addresses. (The system responsible has no mailing address but it certainly also has a name.)

The women of Troy ululated as the city burned. Our modern horrors seem not to erupt out of us but destroy us from within. How do you give voice to all that has been taken from you when it’s everything?

Something I appreciate about Lady Augusta Gregory, knowing nothing else about her, is that she’s one of the few people I’ve ever read who manage to do just that. She was talking about a lover who took everything instead of medical debt or the death of the future via climate apocalypse but her ability to put what feels like the end of all things into words is nevertheless impressive. Here’s the poem I’m thinking of, read out in John Huston’s film version of James Joyce’s novella The Dead:

Huston decided to call the poem “Broken Vows” for the purposes of the film, but it’s actually called “Donal Og” (“Young Donal”). He makes a few other small changes, too, but I think either version is a kick to the teeth.

You have taken the east from me; you have taken the west from me;

you have taken what is before me and what is behind me;

you have taken the moon, you have taken the sun from me;

and my fear is great that you have taken God from me!

I mean, Jesus. What a way to curse someone out.

I promised you earlier that while this would be melancholy it would not be hopeless. And an honest reckoning with the world should always reveal that there are people smarter than you fighting harder than you to fix stuff. (If it doesn’t reveal one or both of those things you’ve got bigger problems than this newsletter can solve.) Perversely, I think I find the most hope in the people who make the things—interviews, books, essays—that are the most honest about just how badly the deck is stacked against us. Hope only feels worth having when it can still exist in the face of the worst scenarios imaginable.

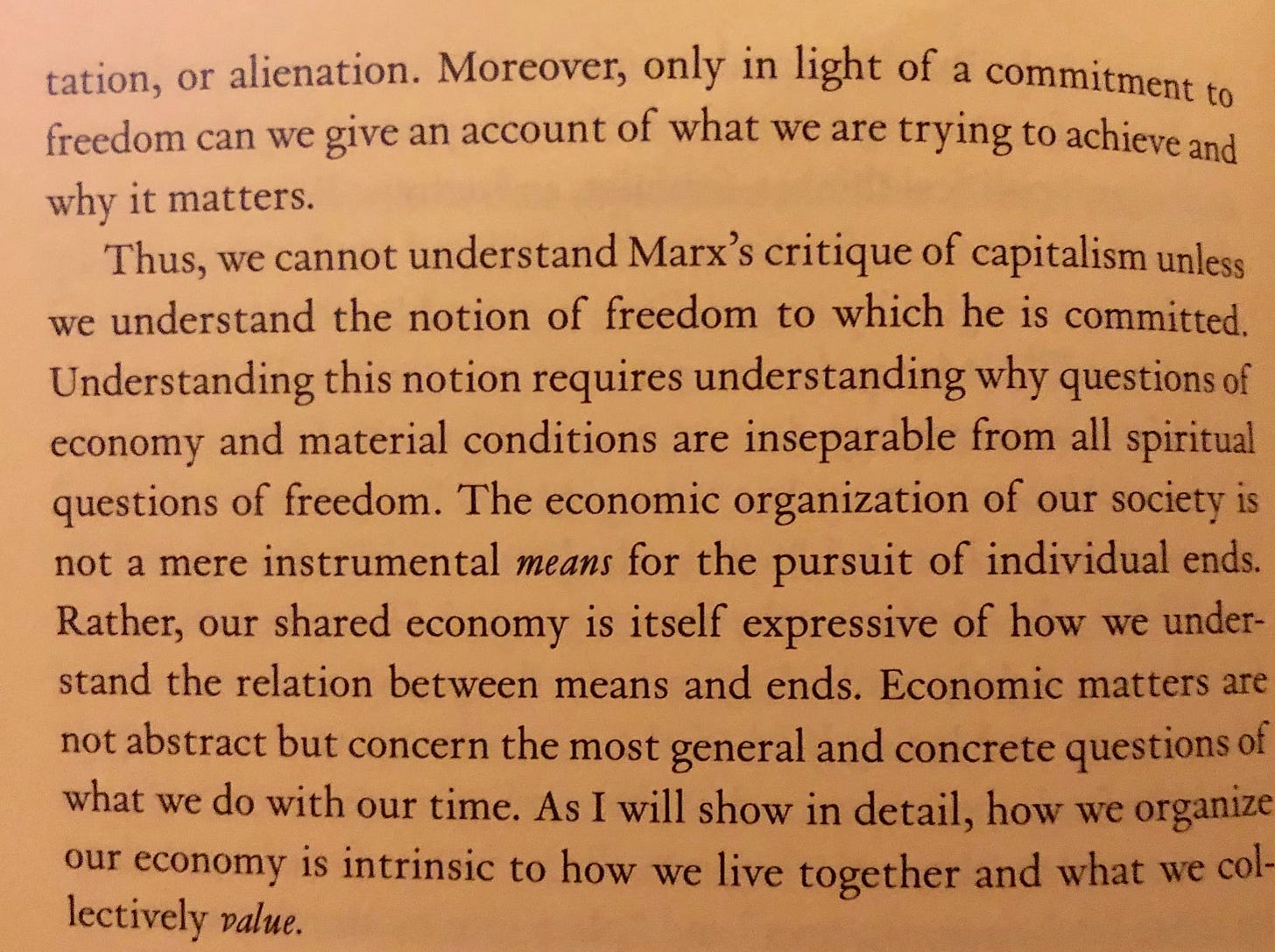

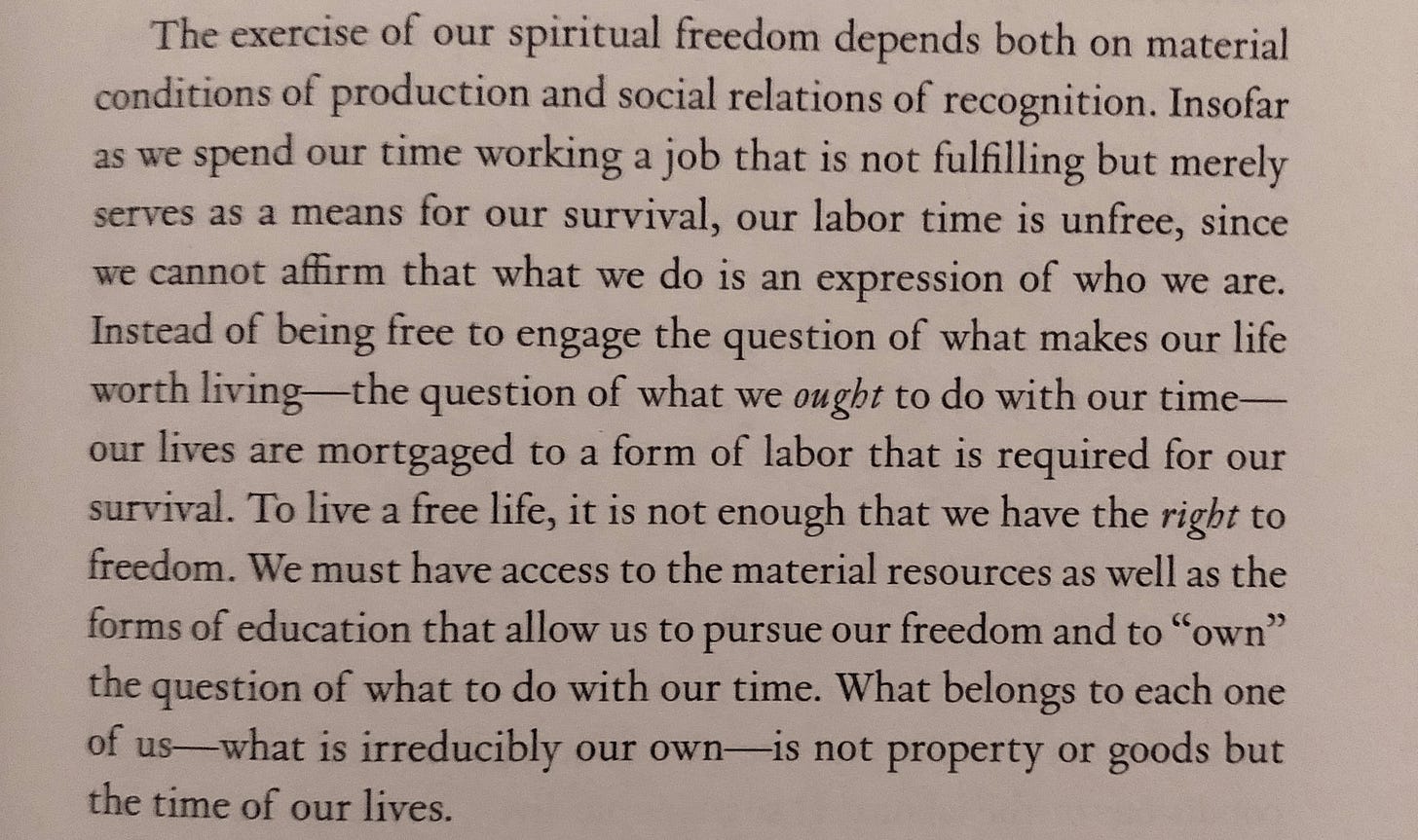

One such person is Swedish philosopher Martin Hägglund. I’m currently wading my way through his This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom. The book makes the case that it’s only in acknowledging life as finite that we can find any meaning in it—in fact, it’s knowing that we’re all going to die that should make us eager to reorganize society in a way as that treats every life as valuable. To wit:

He continues:

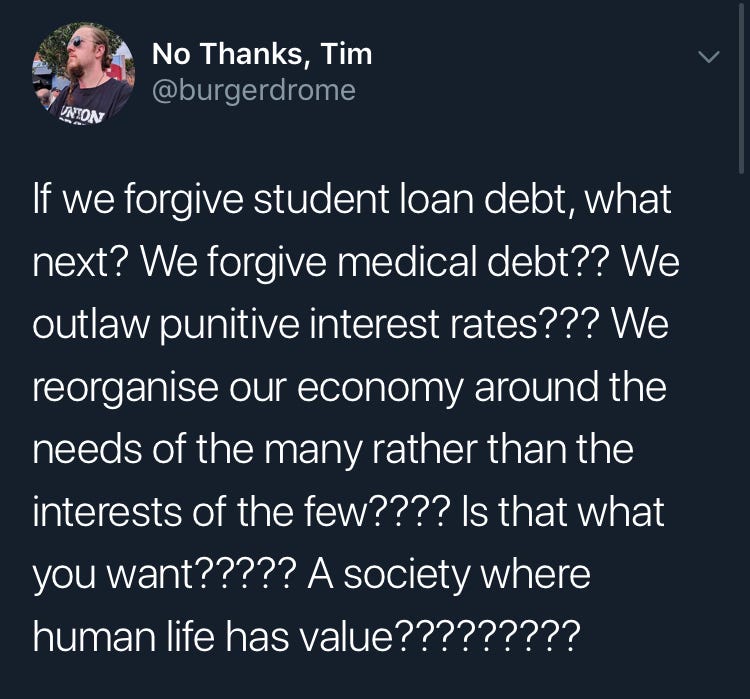

To see how we might imagine the real-world applications of this principle, look no further than the following tweet:

Damn. It took 240 characters to say what Hägglund spun into hundreds of pages.

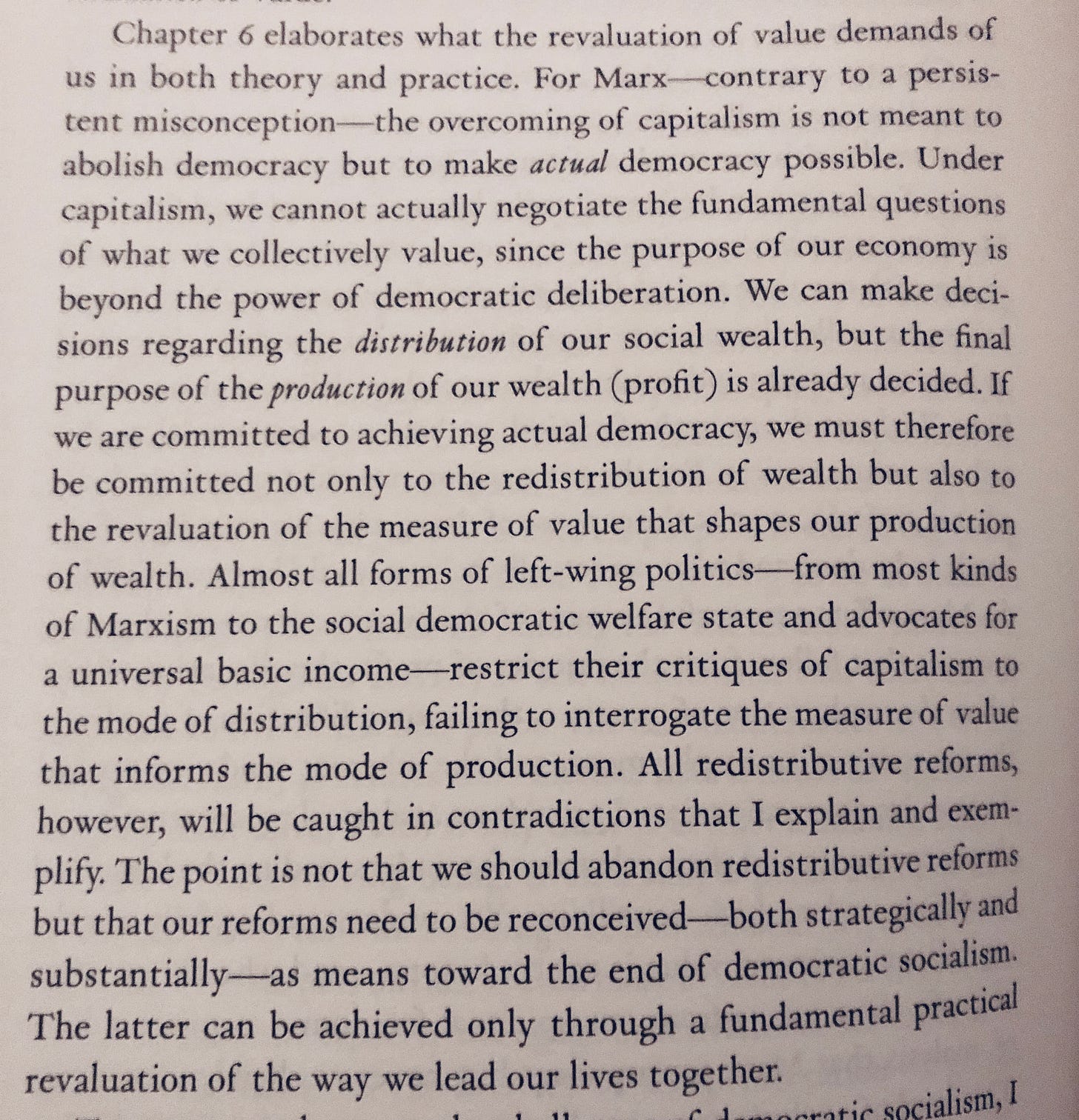

Okay, one last note from him:

All of this is to say that there are some problems with what we as a society value—or at least, our dissatisfaction with that hierarchy of values has not yet managed to erode the system propping it up. So instead most of us spend a third or more of our one shot at a life on this planet doing things we would rather not be doing, at the behest of people we’d rather not be beholden to.

There are, quite obviously, lots of difficult things that do need doing, and even some that don’t that still manage to be personally fulfilling; do not mistake me for a utopian who despises the idea of work. But on the whole I think I fall into the camp of Tim Kreider, who penned an essay I find myself returning to frequently, aptly titled “The Busy Trap”:

I once knew a woman who interned at a magazine where she wasn’t allowed to take lunch hours out, lest she be urgently needed for some reason. This was an entertainment magazine whose raison d’être was obviated when “menu” buttons appeared on remotes, so it’s hard to see this pretense of indispensability as anything other than a form of institutional self-delusion. More and more people in this country no longer make or do anything tangible; if your job wasn’t performed by a cat or a boa constrictor in a Richard Scarry book I’m not sure I believe it’s necessary. I can’t help but wonder whether all this histrionic exhaustion isn’t a way of covering up the fact that most of what we do doesn’t matter.

Easy enough for me to nod in agreement with; I’m a teacher, and I distinctly recall at least one image of a cat in a hideous dress standing in front of a classroom of other creatures in those books. But I think the point stands: we have committed ourselves so unquestioningly to the idea of work that instead of devising more efficient means of distributing the fruits of actual productive labor, or god forbid restructuring society as a whole to value the free time all our efficiency and productivity should be creating, we’re making up things to do whole cloth because everyone needs to have a job. Feels a bit like putting the cart before the horse, no?

Of course the largest share of the blame does not lie with the common people who are doing this work, wrapped up in the ethos of American Protestantism though they may be. It lies with people whose sole project is perpetuating the system—capitalism, I’m comfortable naming it—that must continually extract, or die. Extract apocalyptic fuels from the earth and extract blood from soldiers waging ever more profitable wars. Extract breathable air from the atmosphere and precious hours of finite lives, ad infinitum.

And we should not lose sight of the fact that organizing around this very issue—trying to have a purpose for oneself and a future for everyone—can be a remarkably fulfilling experience! I doubt Greta Thunberg underestimates what she’s up against as a teenager staring down the barrel of climate crisis. But this gives her better perspective from which to be hopeful, not worse:

Along these same lines it seems fitting that one of the people best suited to tell us that the ubiquity of cars in America is terrible is Ray Magliozzi, one of the hosts of Car Talk. It fits, really—he and his brother Tom were mechanical diagnosticians of the highest order, almost entirely unsentimental about the cars themselves.

In the piece linked above, it becomes abundantly clear that to the Magliozzi brothers, the show was never even really about cars: it was about fixing things, and thinking critically, and placing value on the things that are actually important. (Listeners will note that they rarely ever recommended forking over a bunch of money to make a minor upgrade, get a “nice car,” or really…for anything.) And now that it’s irrefutable that our mode of transportation is helping destroy the planet, Magliozzi does not equivocate in saying we should be working to get rid of them.

Should any doubt remain about what Ray and Tom actually valued:

The show’s most frequent listener these days might in fact be Ray himself. He said he still listens to the show “all the time,” mostly to hear his brother’s voice and remind himself about times they had together. To remind himself of the jokes they shared. To remind himself of the good times.

“I love to hear his laugh, and I love to hear his take on things,” Ray said. “It’s a rare opportunity that I’ve had to still communicate with my brother that most people don’t get.”

So I’ll close this week by asking you to think about what it is that you value. Does the world we live in allow you to maximize the time you spend doing that thing, being with those people, exploring those places? (Importantly, do you think that answer is different for people who don’t look like you or fall into a different income bracket, in either direction?) If the answer to the first question is no or the answer to the second is yes, consider how that might be changed. Consider what must be done. And know that other people are already working on those problems that would love to have you along to help.

See you next week.

-Chuck