Tabs Open #33: From This Valley They Say You Are Leaving

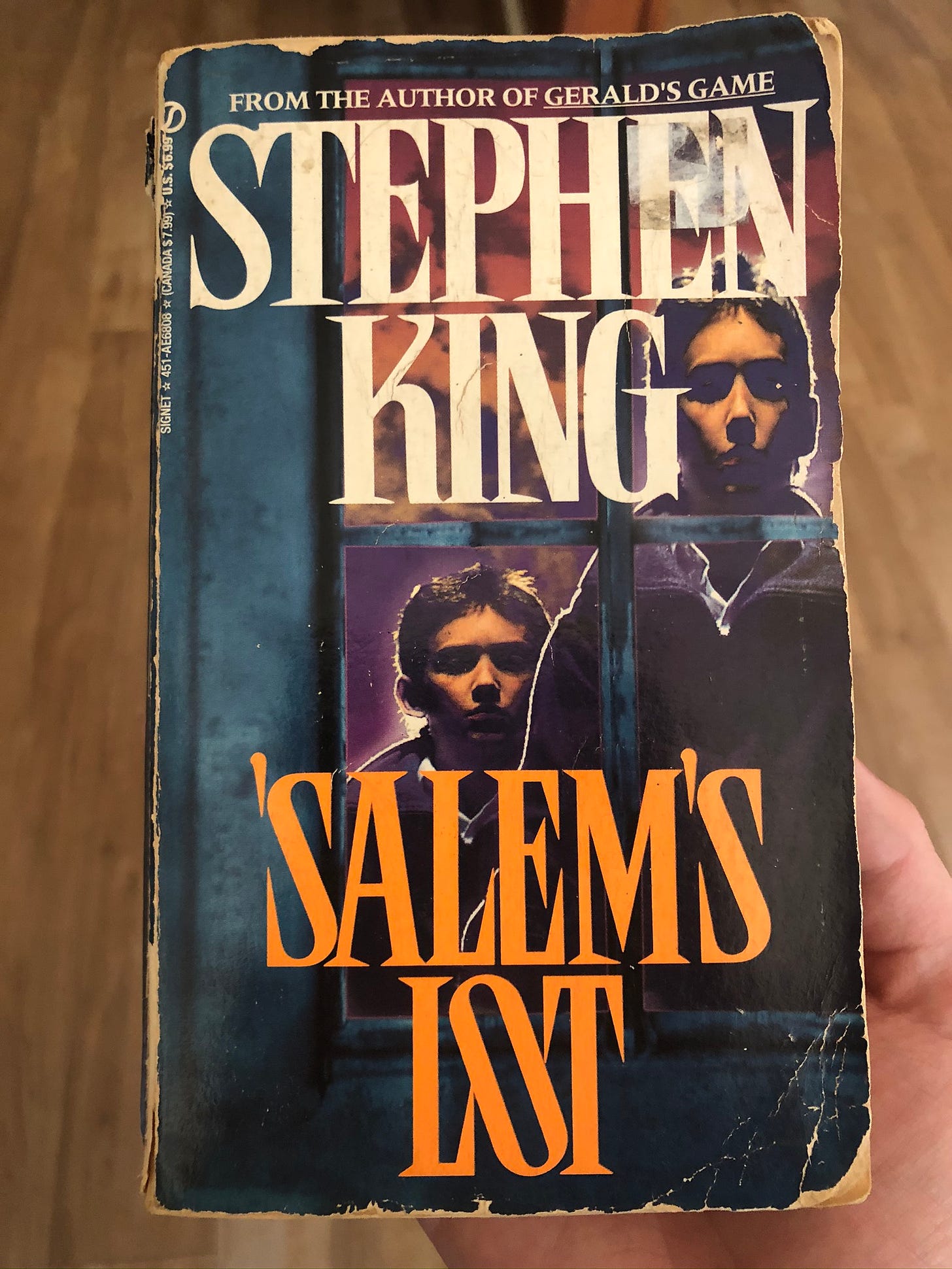

One of the books on the numerous shelves that make my tiny apartment seem even tinier is a tattered, yellowed copy of Stephen King’s ‘Salem’s Lot, the product of some 50-cent sale at Half-Price Books. On the blue cover is an illuminated window with the creepy faces of two children peering through. Looking at the cover you wouldn’t know what the book is really about, even if you’ve got your Stephen King bingo card out and can therefore reasonably assume that a) it’s set in New England, b) at least one of the principal characters has a drinking problem, and c) one or a lot of people’s souls are at hazard due to the monstrous forces at work in d) the sleepy little town where the action takes place.

These are all true of ‘Salem’s Lot, which e) takes place as the season turns to fall, the time of year when most of King’s best work is set, but what the story is about is the rapid transformation of an entire town’s worth of people into vampires. All but two people, that is, one of whom is f) a troubled writer with a murky past and a tortured heart.

The transformation of the town’s populace into a small army of the undead is paralleled, in King’s work, by that shifting of the season, the loss of summer’s sweet promises as they are folded into the cold reality of fall’s procession toward death and decay. The season takes on a character of its own in ‘Salem’s Lot, like the woods of New York in The Last of the Mohicans or America itself in On the Road:

But when fall comes, kicking summer out on its treacherous ass as it always does one day sometime after the midpoint of September, it stays awhile like an old friend that you have missed. It settles in the way an old friend will settle into your favorite chair and take out his pipe and light it and then fill the afternoon with stories of places he has been and things he has done since last he saw you.

Or:

The sun loses its thin grip on the air first, turning it cold, making it remember that winter is coming and winter will be long. Thin clouds form, and the shadows lengthen out. They have no breadth, as summer shadows have; there are no leaves on the trees or fat clouds in the sky to make them thick. They are gaunt, mean shadows that bite the ground like teeth.

So this is a season that lends itself to thoughts of transformation. A rolling tide of metamorphosis, a retreat within.

I have been off of Facebook and Twitter for two weeks now and while I am under no illusion that that transformation is permanent, it is important to our tale in the sense that I have been watching a lot of X-Files episodes with all my newfound free time. One of the episodes I saw most recently—and I will keep this brief, because literally nothing is more annoying than someone explaining to you at great length the plot of a TV show you’ve never seen—concerns a series of possible werewolf killings that coincide with a land dispute between white ranchers and the local indigenous tribe. Lacking any social media outlet with which to immediately distract myself afterward, I instead found myself deep in an internet rabbit-hole of animal transformation stories.

It should probably be unsurprising that stories of humans that become beasts and vice versa date back to times when the line between human and beast as two distinct categories was blurrier. As Barbara Ehrenreich recently explained in an excellent essay on cave painting,

Yet despite the tricky and life-threatening relationship between Paleolithic humans and the megafauna that comprised so much of their environment, twentieth-century scholars tended to claim cave art as evidence of an unalloyed triumph for our species…But the stick figures found in caves like Lascaux and Chauvet do not radiate triumph. By the standards of our own time, they are excessively self-effacing and, compared to the animals portrayed around them, pathetically weak. If these faceless creatures were actually grinning in triumph, we would of course have no way of knowing it.

While twentieth-century archeologists tended to solemnize prehistoric art as “magico-religious” or “shamanic,” today’s more secular viewers sometimes detect a vein of sheer silliness. For example, shifting to another time and painting surface, India’s Mesolithic rock art portrays few human stick figures; those that are portrayed have been described by modern viewers as “comical,” “animalized” and “grotesque.” Or consider the famed “birdman” image at Lascaux, in which a stick figure with a long skinny erection falls backwards at the approach of a bison.

There is of course a good bit of breathing room between the slavering jaws of the werewolf and the horny bird-headed guy falling over, slapstick style, in front of prehistoric megafauna. But these stories of transformation have clearly captivated people for as long as people have been people, and the stories stay basically the same, even if there are some minor variations on the theme.

Take the bultungin, the werehyenas of East Africa. While they’re largely absent from Western myths they were feared throughout the eastern hemisphere of old, with everyone from the Persians to the Sudanese to the Greeks getting in on the action. The Greeks had werewolves, too—it’s clear that the ancient world had a prevailing belief that what they reviled had the power to transform them. And it wasn’t just the ancients: it turns out that our modern understanding of the vampire as a pale and charming aristocrat originally comes not from Dracula but from a little known work called "The Vampyre,” written by Lord Byron’s personal physician, who detested the handsome Lothario for all the ways in which Byron drained the life out of him. (That tale was born out of the same night of ghost stories that saw Mary Shelley create Frankenstein. A pretty important party, as parties go.)

Here’s a brief pause from the changes of seasons and monsters.

He transformed that mud into an oven and that carcass into a meal pretty deftly, I’d say. I’ve watched that video probably thirty times and I want to jump into it and help eat that chicken.

At the risk of making a clumsy sort of segue here I want to call your attention to a different sort of monster transformation narrative, because it appears that I am constitutionally incapable of going a single issue of this newsletter without tying it back to my political worldview. (Then again perhaps I am being overly cautious; there is probably not much overlap between the group of people who read this publication every week and the much larger group of people who do not care one bit about my worldview.)

In 2013 the British socialist Mark Fisher penned an essay titled “Exiting the Vampires’ Castle.” It has caused quite a bit of controversy in Leftist circles in the years since, as it is a significant departure from the orthodoxy of Left political spaces, especially as they exist on campus. I don’t agree with all of Fisher’s conclusions and the essay occasionally reads as too forceful a blow but I do recognize that I am about as non-confrontational as it’s possible to get and part of my anxiety about it stems from battles that exist strictly in my imagination.

The “Vampires’ Castle” in question for Fisher is culture of moralizing and condemnation (what we in 2019 would call “cancelling”) devoid of any real ideological underpinning. Fisher argues that the motivation here is to separate issues of class from issues of race or gender or sexuality, such that any movement toward class consciousness can be dismissed out of hand as inadequately concerned with historical and present injustices that do exist along more identity-based lines. (This tension has emerged, either implicitly or explicitly, at conservatively 80% of DSA meetings I have ever attended, so I feel like his analysis—coming 3 years before the DSA membership boom of 2016—was particularly prescient.) The effect of all this is a Left that is doomed to marginality forever, a Left that cannot and will not engage in real power struggles with capital interests. Fisher describes it as a project of purifying the ranks of heretics rather than attempting to win converts.

I can’t help but see a connection here: in the world of ostensibly progressive-minded people, we have replicated the phenomena that paralyzed the Athenians and Tunisians and Igbo and Algonquins and whoever else, writing our story such that what terrifies us has also transformed us. Capitalism’s body count is an awful lot higher than the sum total of wolf kills or hyena kills or whatever else used to terrorize us out on the plains, even if it is a decidedly less sexy villain.

A bit from the essay that I quite like is as follows (emphasis mine):

A left that does not have class at its core can only be a liberal pressure group. Class consciousness is always double: it involves a simultaneous knowledge of the way in which class frames and shapes all experience, and a knowledge of the particular position that we occupy in the class structure…the aim of our struggle is not recognition by the bourgeoisie, nor even the destruction of the bourgeoisie itself. It is the class structure – a structure that wounds everyone, even those who materially profit from it – that must be destroyed. The interests of the working class are the interests of all; the interests of the bourgeoisie are the interests of capital, which are the interests of no-one. Our struggle must be towards the construction of a new and surprising world, not the preservation of identities shaped and distorted by capital.

If this seems like a forbidding and daunting task, it is. But we can start to engage in many prefigurative activities right now…We need to learn, or re-learn, how to build comradeship and solidarity instead of doing capital’s work for it by condemning and abusing each other. This doesn’t mean, of course, that we must always agree – on the contrary, we must create conditions where disagreement can take place without fear of exclusion and excommunication.

Fisher also links to a Russell Brand interview that I think illustrates this point well. Instead of continuing to drone on I’ll share it here so you can watch it yourself.

I think that’s enough to chew on for this week. I’ll leave you with a little tune that feels like it could be about the feeling of nostalgia for summer’s promise that always seems to come when the leaves begin to turn.

Just remember the Red River Valley,

Chuck