Tabs Open #41: Look For It To His West After Sunrise

For most of my life my family has made an annual summer trip down to Buckroe Beach, Virginia, where my grandma’s cousin used to own a tiny, breezy cottage right on the shore. My memories of that place as it was then and the adventures we had there would fill weeks’ worth of this newsletter; I’ll save those reminiscences for warmer months. But one small thing does stand out that I wanted to share with you.

At the foot of the stairs leading to the front porch of the cottage—I always considered it the back porch, as it faced the road and not the ocean, but the builder and the mailman didn’t ask my opinion—was a fragrant bush. It had an earthy, sensuous smell that always seemed out of place to me in such a warm and bright setting. I never knew what it was called, only had that vivid scent memory, until I moved to Seattle in 2013. Turns out it grows everywhere here and it’s just plain old rosemary.

It has become a furtive treat to walk around my neighborhood whenever I’m in need of fresh rosemary for a recipe and just break off a few sprigs. I’ve come to know five or six locations where this can be done; there’s always a fleeting second of guilt and a panicked glance around before I take it, but I acknowledge this is silly. As it grows outside apartment buildings there’s no one to ask permission from, but it feels like more of a public utility than a private good anyway. If we can’t all have healthcare I can at least pluck some herbs, right?

I’m only thinking about this at all because as I sit down to write to you I have this Lemon Garlic & Rosemary Roast Chicken from Bowl Of Delicious in the oven and it is almost debilitatingly aromatic. I get nostalgic every time I chop rosemary and tonight was no different.

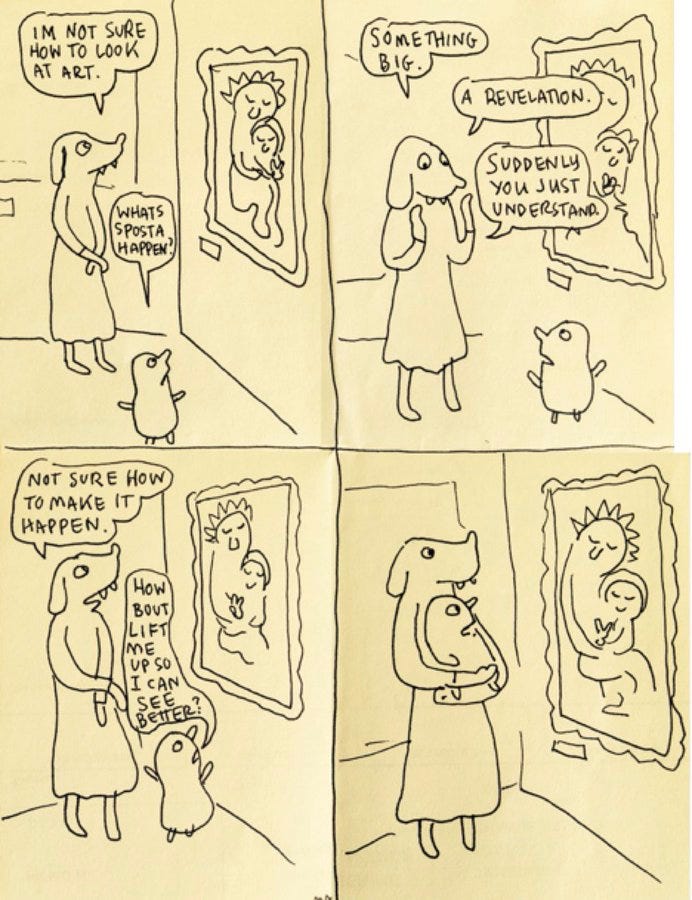

Anyway here is some art I thought you might like to see. From Lynda Barry:

I first saw that right before I went to the Met in New York a few weeks back and I think it put me in the right frame of mind before I went inside.

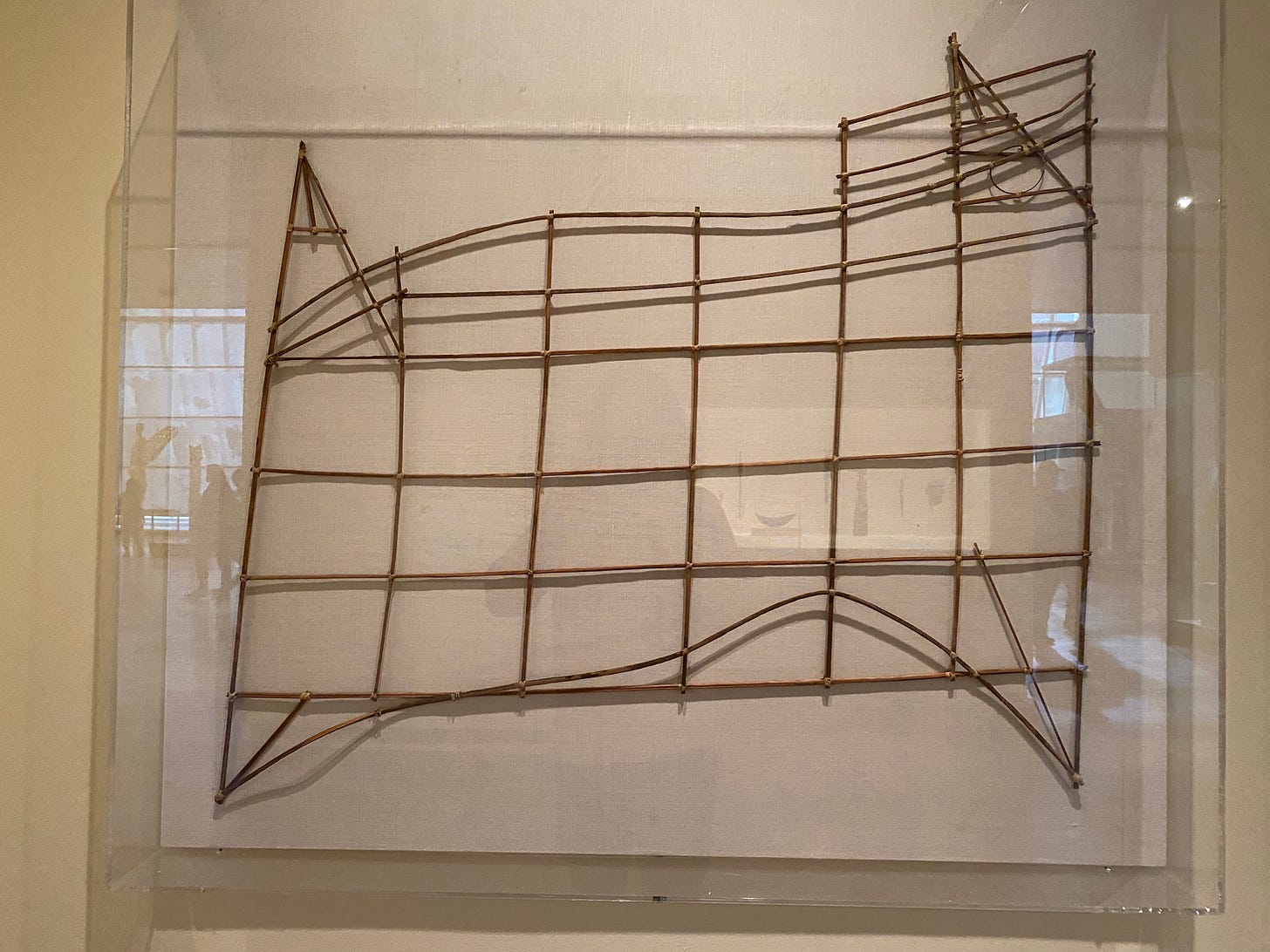

At the Met there is a lot of art, obviously, but there are also cultural artifacts from all over the world—the construction of which is also clearly an artistic process. Their proximity within the museum does elide quite a bit of space and time, though. In a matter of minutes we wandered from Egyptian pottery and sarcophagi from 5,000 years ago to an exhibit on the Pacific where I came across the following object:

This is a Marshallese stick chart from the early 20th century. Marshallese wave pilots used charts like this to navigate for several millennia, but only one, Alson Kelen, still uses the old techniques today.

In the cabin, Genz heard Kelen’s voice on the radio again. Kelen could see the lights of the Jebro behind him, he said, and he thought they were about 10 miles east of Aur. Because they were approaching its reef too fast, his plan was to overshoot it, then look for it to his west after sunrise. Genz glanced at the boat’s GPS device and realized that Kelen, over the last decade, might have learned more than he had ever let on. He wanted to shout congratulations.

‘‘Copy that,’’ he said instead.

The story that quote’s pulled from is a fascinating one, charting a research team’s attempts to discover the scientific basis for what Marshallese navigators have known for thousands of years: how to use the unique patterns of waves and their relationship to each other to chart courses by feel across a vast ocean. They set out to find the di lep, the “backbone” of the waves, to prove or dismiss its existence. (Also if you read it you will see a picture of three researchers sitting at a table outside a church on Aur, the island where I lived and taught right after college. I’ve sat at the same table dozens of times—eerie to see it in the New York Times, of all places.)

Me in 2013 on Aur, toward the end of my year as an English teacher there.

This study was done with the full participation of the Marshallese navigators, but it does also fit into the category of Americans demanding proof for truths indigenous people of the current and former colonies already know. (I previously wrote about how I teach the story of The Really Big One—the earthquake that’s due to destroy the Pacific Northwest—every year; turns out if seismologists wanted to know when the last time the region was blasted to pieces they could’ve just asked the Huu-ay-aht First Nation or the Makah Tribe, whose oral traditions mark the 1700 earthquake with a high degree of specificity.) I was recently put onto a moving piece about the complex, messy job of unpacking the truth of a battle in Alaska between Russians and the Tlingit people, a battle in which both sides have claimed victory for two centuries.

There are the more obvious reasons why the Tlingit side of the story was seldom-shared in America; our national myth-making is dealt a blow by recognizing the humanity, ingenuity, and resilience of the people from whom the land was taken. But there’s another angle, too, one that feels tied to the Marshallese navigators and the Makah earthquake witnesses.

There is almost no way to describe the Tlingit concept of ownership without distorting or reducing its complexities. Clans “own” their regalia and their crests, but they also own their ancestral relationships to a place, their songs and dances, their stories and the images that came from those stories. If branding and intellectual property rights were taken to an extreme and merged with the Marxist ideal that people must not be alienated from the objects of their labor—nor from the collective identity arising from that labor—then we might approach the Tlingit sense of ownership. The word for this is at.óow, which has been translated as “a purchased thing.” The Battle of Sitka was a purchased thing. It was paid for by the Kiks.ádi, and it could not be sold out.

Who owns a story? Who deserves to hear it? These are questions without universal answers. The Marshallese happily let western scientists investigate the underpinnings of their navigational traditions because there are so few people alive to preserve them, because the Marshallese relationship with the America that detonated nukes on its islands is still both productive and complicated, because they know that their methods work whether or not scientific proof about the di lep is found. The Makah and Huu-ay-aht went centuries without sharing their vital information, mostly because they were never asked. And the Tlingit mostly protect their stories, because they are their stories.

There are as many answers to these questions as there are people.

I promised you art, and while we’re on the subject of Alaska, good god would you look at these Sydney Laurence paintings.

Anyway I’m gonna meditate on these paintings for awhile. Last night I for some reason decided to watch a presidential primary debate in which the need for constant war and the silliness of providing free healthcare were both assumed by all moderators, and during the rare commercial breaks I was bombarded by ads for the health insurance lobby and a piece of shit “E Verify Works” site that exists solely to persecute undocumented immigrants. Awesome, hopeful stuff.

I’ll try to end on a high note, at least for the Irish nationalists among you. “Come Out Ye Black & Tans” briefly made it atop the charts in the UK last week despite being ~100 years old. “Show your wife how you won medals down in Flanders” remains a devastating insult.

I’ll catch you next week. Take care of yourselves.

-Chuck