Tabs Open #48: The Mountain Glen I'll Meet At Morning Early

Around this time every year, I find myself re-watching a host of my favorite Irish films. In recent years this has come to include Ken Loach’s 2006 masterpiece The Wind That Shakes the Barley, the story of two brothers torn apart by the fight for Irish nationalism in the early 1920s. Cillian Murphy—who is somehow arrestingly handsome despite the fact that you can sort of see his whole skull at all times—stars.

There are a number of scenes that are hard to shake, from the execution of a friend-turned-spy to the forced head-shaving of a woman caught collaborating with the IRA. But one quieter bit that really sticks with me comes from a prison scene, the night before Damien (played by Murphy) and Dan (played by Liam Cunningham, better known as Ser Davos Seaworth) have been sentenced to die. They ruminate on what it is they’ve been fighting for, the Ireland they wanted to build—a shared vision first advanced by socialist orator James Connolly:

If you remove the English Army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organization of the Socialist Republic your efforts will be in vain. England will still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and individualist institutions she has planted in this country and watered with the tears of our mothers and the blood of our martyrs.

It is not, in other words, enough to change the color of the flag (or the color of the ruling party, in American terms). You must fight to build a fundamentally different world predicated on justice and equality, absent the institutions that inherently exploit regular people no matter how many gilded coats they’re painted with.

The community portrayed in the film splits over the spirit of that Connolly quote: the landed and respected pro-Treaty IRA accept peace with England with the belief that nominal Irish rule of Ireland is the best they can get, while the anti-Treaty IRA reject its terms outright, refusing to accept any accord that doesn’t cede full control of Ireland to its people—the workers, not just the aforementioned landlords and financiers. (Given that Ireland is not currently a unified socialist republic, you can guess how that works out for them in the film. But when has “it’s likely to win” ever factored into the moral calculus of an issue?)

Anyway I did not want to write about the pandemic this week, as you’re more than likely overwhelmed and over-saturated with it by now. But I can’t help seeing echoes of Connolly in this current crisis, and how it has laid bare the need to fundamentally overhaul just about any system in this country you could name: utilities, so that no one ever loses life-giving access to water or heat; housing, so that no person is without a place to quarantine; education, so that kids without school are not kids without food. And then of course the granddaddy of them all, healthcare.

One illustrative example comes to us courtesy of Gilead, a company you might previously have heard of because of their PR crisis surrounding PrEP, the HIV prevention drug that they’re charging $1,758 a dose for. Anyway Gilead has the most promising version to date of the COVID-19 vaccine, which they plan to sell for $50 or $100 a dose, and they’re suing to prevent China from having access because they believe China would give it away for free. Perish the thought—prioritizing the health of everyone over the health of only those who can afford it!

(You may be asking, Chuck, doesn’t Gilead’s quick development prove the need for privatized pharmaceutical companies that can innovate quickly precisely because they have so much money? And it’s a fair question. But the answer to it is “no.” Pharmaceutical companies are profiting, in many cases, off of research done by the CDC—as is the case with PrEP; many are also profiting off of drugs developed through research funded by government grants. We are subsidizing the research, in other words, just to have the end result sold back to us at exorbitant sums.)

It is in the public interest that everyone be able to access the medicine they need. And it’s becoming clear to a lot of people that this is the case when we look at coronavirus. The trick from here is figuring out how to make people reckon with the fact that if it’s true for this crisis, it shouldn’t be any less true for cancer or diabetes or…you name it.

Okay one more quick laugh/cry for you before I get off this topic:

Enough about these vultures. Today’s a day for reckoning with the stories of the Irish, which are important not because they’re unique, but because they’re not--there are 30 million people of Irish ancestry in the U.S. alone. And so the stories of the Irish are the stories of us all, in crises of every stripe.

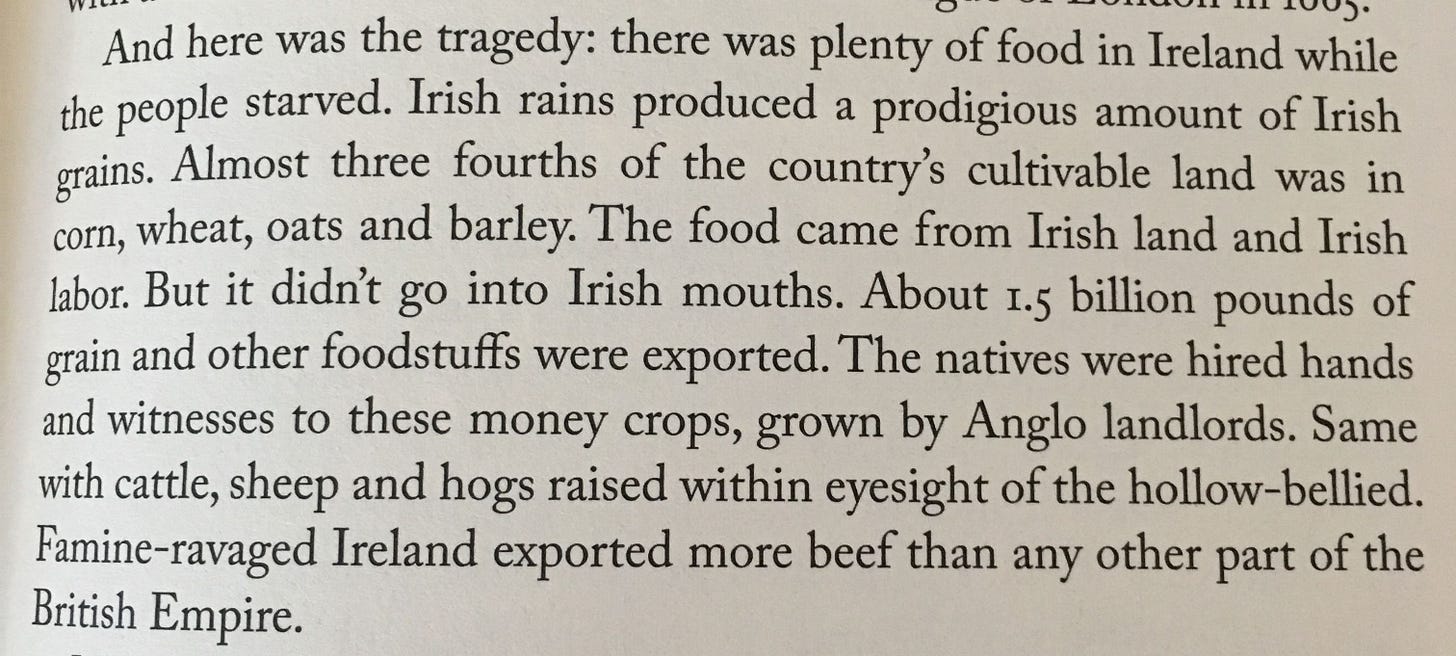

Consider the Irish potato famine, perhaps one of the most poorly-understood moments in European history, at least in America. Did millions of Irish starve because a blight decimated the main source of food for all Irishmen, the potato? No. They starved because England seized all other viable sources of food, and actively prevented relief food from being brought in to save the Irish by the caring nations of the world.

These excerpts come from Timothy Egan’s The Immortal Irishman, which is not a description of every thinking person’s nightmare but rather an honorific given to Thomas Meagher. Meagher was a hero of the Irish revolutionary movement of the 1840s who ended up imprisoned in Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) before escaping to San Francisco and eventually becoming a Civil War hero and the governor of Montana. As it was in 1845, it is today. Our problem is not one of supply, it is one of malfeasance, woven into the fabric of a nation so thoroughly that it creates its own inescapable logic. But what will it do to the markets, they asked as millions starved. And here we are almost 200 years later operating under the same pitiless thumb.

Fortunately for us, blossoming from the centuries-long drubbing of the Irish is their indomitable revolutionary spirit. One defiant song that came out of the famine, sung here by Paddy Reilly of The Dubliners, is “The Fields of Athenry.”

In the song a young man faces the penalty of transportation—shipped off to Australia or New Zealand to be indefinitely imprisoned—for the crime of stealing government corn to feed his wife and child. That the British rulers of Ireland saw that massive penalty fair for such a petty crime shows that feeding the Irish, or refusing to, was never about the cost—it was about control.

A more recent lament on the 20th century version of these struggles comes to us from the pipes of Luke Kelly, also of The Dubliners, singing in 1973 of the strife tearing apart Derry (officially Londonderry), a heavily Catholic city in Protestant Northern Ireland:

Luke Kelly was himself a dyed-in-the-wool socialist agitator, styling himself as a sort of Irish Pete Seeger. Like James Connolly, Kelly—though a singer, not a politician—understood that true Irish freedom would have to involve Irish socialism. It would not have to be invented entirely, either: Kelly’s vision of a just world drew heavily on the lessons of America, from the Civil Rights Movement to the Wobblies and the labor movement:

The Dubliners produced an album entitled Revolution in 1970, launched in Dublin’s Kilmainham Jail where the leaders of the 1916 Rising had been executed. Revolution lived up to its name in both form and content, with a piano, bass and second guitar added to the band’s musical arrangement. The tracks also amounted to its most political oeuvre to date, with songs including American civil rights ballad Alabama 1958, labor anthem Joe Hill, anti-nuclear weapons song The Button Pusher, as well as anti-fascist tune The Peat Bog Soldiers.

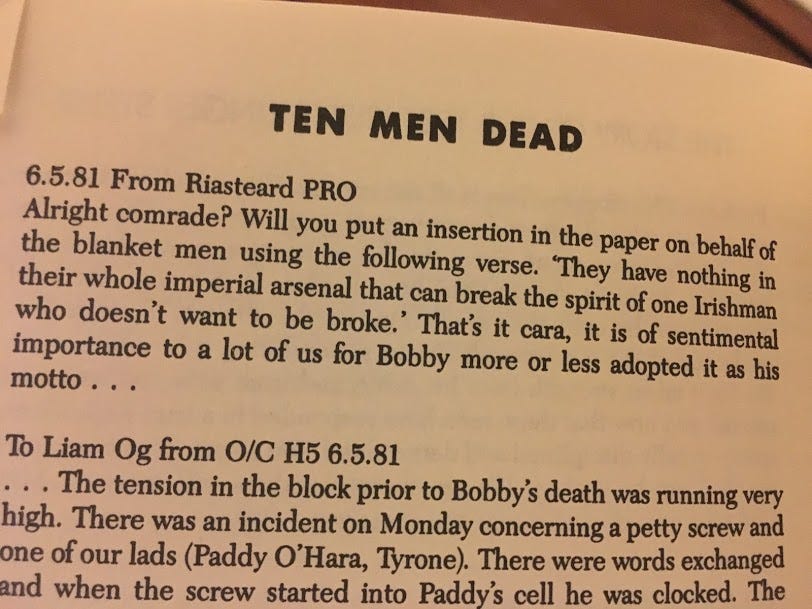

The debate about socialism’s place in Ireland wasn’t some niche thing in the time of the Troubles, either. It was a hotly debated issue among political prisoners at Long Kesh, the home of every IRA man the Northern Irish government was able to round up in those days, including the ten hunger strikers—led by Bobby Sands—who died in 1981.

Sands, it should be said, marched to his death with clearer eyes than most. In a note smuggled out to IRA leadership responding to questions about his mental state as death approached, he cheekily wrote:

Some ask for cigarettes, others ask for blindfolds, yer man asks for Poetry.

That bit comes to us courtesy of David Beresford’s groundbreaking Ten Men Dead, put together from the author’s unprecedented access to the IRA’s archive of “comms”—the scraps of toilet paper and other materials upon which messages were smuggled in and out of the Kesh during the turbulent period of the hunger strike.

This is quickly devolving into a series of recommendations about Irish stuff I like, so why don’t I just put that together formally here.

Books

Ten Men Dead, David Beresford

The Immortal Irishman, Timothy Egan

The Troubles, Tim Pat Coogan

Films

The Wind That Shakes The Barley (2006)

Waking Ned Devine (1998)

The Secret of Roan Inish (1995)

Song of the Sea (2014)

Poems

Music

Truly there are too many wonderful songs to even attempt to begin listing, but this is one of my all-time favorites, the ballad of an Irishman who falls in love in Louisiana:

Anyway I think that should do it for this week. If all goes well that book of mine I’ve been teasing in here occasionally should be ready for orders in a few short weeks; I’ll keep you posted in this space. Take care of yourselves.

-Chuck