The Grinch's Heart Will Not Grow Three Sizes Larger

There’s a certain power that is stopping them from going full steam ahead with the war

Last week’s newsletter is already one of the most read and shared I’ve ever written, so I wanted to follow up a little bit on some of what I wrote, now that we’ve had another week to process and protest and talk about what’s going on in the world. (And thank you, by the way, to everyone who did share it.) This is going to be quite long because there are a lot of issues playing out in real time that are worth connecting, and because the sources I want to draw from to explain my thinking here are so good that I can’t help but pull in a lot more quotes than usual. Apologies in advance.

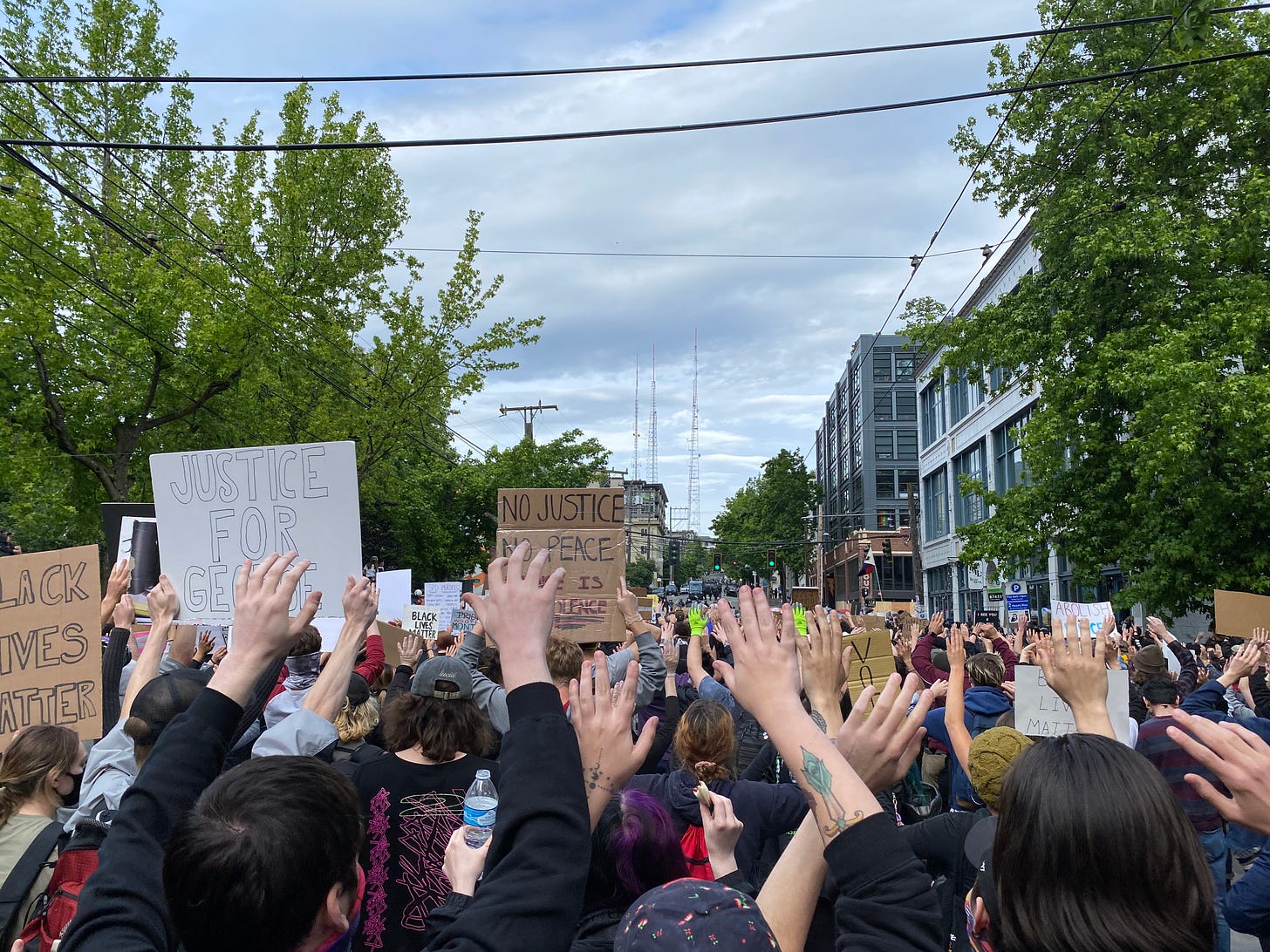

I’m writing this through the lens of having been out in the streets a few times here in Seattle witnessing both the brutal behavior of the Seattle Police Department and the sort of flailing, desperate desire of the protesters and organizers to turn these demonstrations into some sort of tangible gain. Prior to Wednesday that hadn’t really happened, and if you’ll indulge me I’d like to give some perspective as to why I think that’s the case. (Wednesday’s effort was a different story and felt like a step in the right direction, which I’ll discuss further down.)

The reason is that the first protests in Seattle seemed to follow an essentially liberal framework. I don’t mean that as an insult; “liberal” here is wholly descriptive. Let me lay out the stated demands of the original Seattle protests and then explain what I mean. Per the organizers, as they spoke on the steps of City Hall in the Monday afternoon sun, they were asking for:

Mayor Jenny Durkan to come out and meet the protest, and to make a statement

Ditto for Police Chief Carmen Best

Protesters to flood the mayor’s office with calls and emails expressing their demands for police accountability and reform

The protest to be recognized as peaceful

Other speakers did mention things like demilitarization of the police force, diverting funding away from SPD and toward housing and schools, and the like. But the above bullet points were the meat of the official position between last Friday and this Tuesday, as much as one could be given.

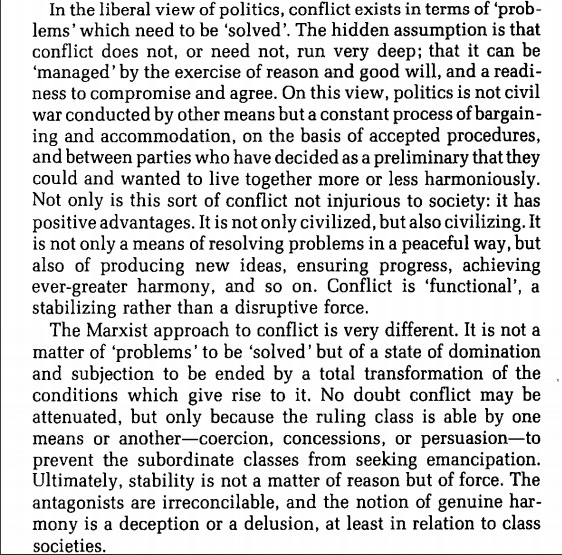

To assert that you are peaceful and that you want to negotiate with the mayor to get certain promises exemplifies what Ralph Miliband outlined as the liberal view of conflict, which he counterposed with the Marxist view.

It might seem odd that I’m using this framework to describe a situation that did, each night between Friday and Tuesday, become actively confrontational. But those eruptions, instigated by police, were largely disconnected from the actual demands being made. Miliband wrote this of protests and the like:

Eruptions, outbursts, revolts, revolutions, are only the most visible manifestations of a permanent alienation and conflict, signs that the contradictions in the social system are growing and that the struggle between contending classes is assuming sharper or irrepressible forms. These contending classes are locked in a situation of domination and subjection from which there is no escape except through the total transformation of the mode of production.

The contradictions in our social system are certainly growing; I’ve been heartened to see how many of my otherwise apolitical or generally polite and institutionally faithful friends have risen to the challenge of this moment. Maybe you have too. Protests are an important piece of changing the system because of what they bring into view—the language of the unheard, as Martin Luther King famously said—and it’s been especially clear to me here in Seattle that the protests are larger than the loose list of demands they were originally nominally attached to.

But it’s worth examining, I think, why it’s so hard to make demands of a government even when the vast majority of people would agree that your demands are just. For this we have to acknowledge that the governance of cities (and states and nations) is currently inextricable from capitalism—the system in which there are very few people who own the things required for a society to produce what its people need, and most everyone else has to work for those people to get their needs met. Seattle is an easy example to use when drawing the connection between this mode of production and the governance of a city because we have Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates here, though it’s just as true whether you’re in Portland or Des Moines or Gainesville. The heads of Amazon and Microsoft typically have more sway with the Seattle mayor than any 10,000 protesters do, because it is their productive enterprise that keeps people employed and indirectly allows the city (through sales taxes, though crucially not income taxes) to fund things. And when the city can’t fund things (in our case, again, because there is no income tax), the corporations are more than happy to step in and generate some more profit by filling the need. (An example that comes to mind is that at one of downtown Seattle’s busiest bus stops, the video board where you track arrival times also includes the time it would take an Uber to get to you and a code for 25% off your first Uber ride. )

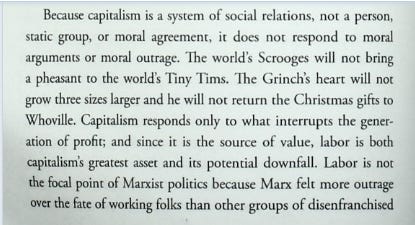

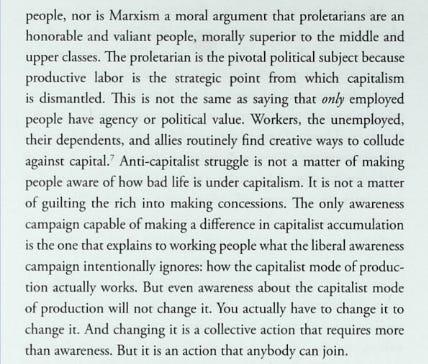

Alright, that’s all true, you may be saying. But can’t we still appeal to the better nature of the parties involved when we want things to change? Holly Lewis wrote about this in The Politics of Everybody:

I’m sorry for making you read so much tiny text, I really am. But Miliband and Lewis both cut to the heart of the problem here, and I think start to illuminate a way out of it.

Now you may also be thinking, okay, we’re not exactly appealing to the better nature of a mayor like Jenny Durkan, who is who she is. (Whether you prefer the Scrooge analogy or the Grinch is entirely up to you.) But doesn’t a sustained show of human force and determination in the streets count for something? Can’t that be enough to change the calculus on its own?

My response to that is in large part influenced by Peter Camejo’s 1970 speech titled “Liberalism, Ultra-Leftism, or Mass Action,” which savvy Tabs Open readers will note I have cited on at least two other occasions.

Nixon says the US isn’t sending any more troops. The troops are supposed to be withdrawn from Cambodia by the end of June. But Nixon is pulling them out just when the United States is losing in Cambodia!

Now, that’s very unusual. We have to stop and think: what’s stopping the United States from sending hundreds of thousands of troops into Cambodia right now, to take over the capital and secure all those little towns and cities and roads and everything else they claim they’re losing? They certainly don’t want to lose Cambodia. Nixon has the airplanes, he has the ships. What’s stopping him? Russian troops? Chinese troops? Who’s in the way?

If you can’t answer that question, you can’t understand either what is happening in this country or what has to be done. Because if you want to deal with politics, you have to understand that there’s some real force stopping the war-makers. It’s not just some psychological quirk of Nixon. And it’s not because of some resolution that’s being debated by the Senate. The power of a class, like the American ruling class, is not determined by some kind of legal paper.

It’s determined by a relationship of certain forces. In other words, there’s a certain power that is stopping them from going full steam ahead with the war. What is that power?

That’s the real question: where does power come from, and where does it lie currently? It’s telling that liberals with power don’t ever want to honestly answer this question. When Jenny Durkan addressed the assembled crowd of thousands on Wednesday, she told us, “I acknowledge I have great privilege in my position as mayor.” No, she doesn’t. She has power. She has the police force at her disposal, she has the ability to set policy and pass budgets and make decrees. Those aren’t privileges, and to use social justice speak to obfuscate that—I’m just another concerned white person trying to do better, please help!—is not a slip-up. It’s an intentional obfuscation of the power dynamics at play.

Look at it this way (emphasis mine):

You see, if you walk into a store that’s selling refrigerators, there’s nobody in that store to stop you from wheeling out a refrigerator. How many guards do they have at the door? Probably zero. They have some salesman who walks up to you. It wouldn’t take much to get him out of the way. You could wheel out four or five of them.

Now, the reason you don’t go wheeling refrigerators out of stores every day of the week is because there’s a certain power ensuring that that refrigerator stays inside the store unless they get money for it. There are things like the police, the courts, and jails behind it. But this power isn’t apparent when you look at the refrigerator and at the little salesman saying, “You’d better not take that.”

In a similar way, when a union bureaucrat gets up at a rally and says, “You’d better stop the war,” it isn’t some helpless little guy on the street talking. There’s a lot of power behind that plea.

If you don’t understand the relationships which exist in this society, because they’re not apparent at first sight, you can make some tragic errors.

The working class and the oppressed nationalities are mass social layers, and they can only realize their potential power when they organize as a massive social force. The ruling class can deal with any one individual or any small group; it’s only masses that can stand in their way. So the potential power of the working class to stop the war is a big threat.

Now, the people who run this country are not stupid. They are not going to continue blindly along a course when they know there are dangers ahead. No one has to go up to Nixon or Kennedy and say, “If the mood that exists among students were to spread to the workers, and instead of a general student strike there was a general strike of the working class, well, then you would lose more than Vietnam and Cambodia.”

No one has to tell them that. They know that. And that’s why they don’t just keep pushing ahead, saying to hell with the students and workers, send in another million soldiers and invade Cambodia. Send troops into Cuba, send them into Indonesia and into China. Drop the bomb on China.

They know better than to just keep pushing ahead. What they have to do is get rid of that danger, the danger that actions will bring a response from the masses who actually have power to stop them. They’re not so stupid as to just go blindly forward. Because where there’s real power, and real stakes, people don’t play games.

You see, you can take 200 or 300, or even a few thousand people and fight in the streets, throwing rocks at windows, and putting on a big show. You can play revolution, not make revolution. But when you’re talking about 15 million workers who control basic industry in this country, you don’t play games. Because they don’t run around throwing things at windows. They do things like stop production, period.

The postmen, for instance — all they had to do to tie up the economy was to go home. That’s all. Just go home. That’s power.

Now, I feel a little differently about protests than Camejo, especially when we consider that this isn’t just a Seattle or Chicago or Oakland or New York protest. We have also seen that, for now, the ruling class of this country still isn’t done pushing, and maybe they have pushed too far this time. Maybe.

But maybe not. Maybe the rapid radicalization of suburban moms and apathetic 20-somethings and formerly-problematic grandpas isn’t enough to tip the balance for good. So I was heartened to hear Nikkita Oliver, who ran for mayor against Jenny Durkan in 2017, address the crowd on Wednesday and say in no uncertain terms that the labor movement needed to join the fight. They didn’t kill MLK, she reminded us, until he started agitating the sanitation workers in Memphis to go out on strike. It remains to be seen if the threat of all stripes of people hitting the streets will be considered a credible enough exercise of power to extract meaningful concessions from the government here—but we know, looking to history, that organized workers hitting the streets, meaning they are no longer producing profit, is. It’s one of the only credible threats available to regular people in this country.

(Camejo, writing this in 1970, probably couldn’t have known that eight years down the line the bipartisan project of dismantling union power would begin in earnest. But there’s a reason a group of presidents so outwardly diverse as to include everyone from Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan to both Bushes, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama all participated in the erosion of American labor power. All of their administrations understood what Camejo understood.)

There is a reason why the same administrations that empower brutal police forces to gas peaceful protesters and sweep homeless encampments and impose austerity budgets are so willing to adopt the language of social justice activism. I hear you. I acknowledge you. I need to reflect, and do better. My administration needs to check its privilege. My administration knows that we are on stolen indigenous land, and we need to honor that. They are willing to do this because they benefit from the conflation of moral concessions and material concessions. They want you to believe that their government is simply a collection of individuals who are capable of doing better, and not the human faces on a vast, shadowy system of material relations that is impervious to begging and pleading. My own union is in contract negotiations with our bosses right now, and I have not yet had the temerity to ask my fellow leaders why they think it is that the district acquiesced to every single demand regarding equity, diversity, and inclusion on day one but has told us we should go beg at the state capital if we want raises, as they won’t promise us an extra cent.

With all of this said, I plan to continue protesting and demonstrating. Standing in solidarity with victims of police brutality, asserting forcefully our shared belief that Black Lives Matter—these are morally necessary, in my view. The working class won’t recognize itself as a class of shared interests in demands unless we take every opportunity to show up for one another and to risk things for one another. Seattle’s material demands are on the table—a 50% reduction in the city policing budget, meaning $205 million a year to be redistributed to areas like housing, education, and healthcare. And as we go through this process of trying to create community and solidarity, we must be clear-eyed about why those are our demands and that half-measures and window dressing will not appease us.

Thanks for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck