In recent weeks I’ve written a few times about the impact that big, old trees have on me and the hope they make me feel for the future—that a single living thing can endure and thrive unbothered as whole empires rise and fall.

How about this one, then?

Some quick research shows that the 80,000 year estimate is almost certainly too high. The range of “just” 10,000 to 16,000 years is far more likely given glacial activity in that area. Depending which end of that range you pick, that single living organism has been on earth since about the time the first human beings were arriving in North America or about the time the world’s megafauna all went extinct. The math gets tricky when you go that far back in time but when this tree first sprouted there were probably only 1-5 million human beings on Earth. Scatter the population of present-day Seattle or Washington D.C. across the globe and get rid of everyone else and you have a sense of how long this single organism has existed.

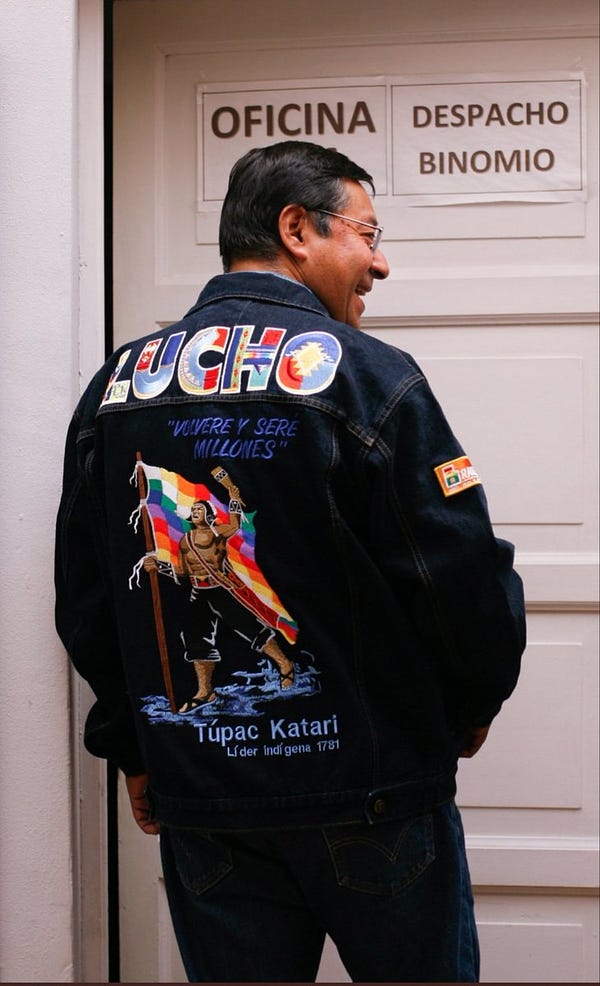

Hope, huh? It feels like it’s getting rarer, and therefore worth calling attention to when felt. This week I experienced just that after what happened in Bolivia: the election of Luis Arce, an ardent socialist, as the country’s new president. This victory—in a landslide, with Arce earning 52% of the vote despite there being five candidates in the race—is monumental not just because someone who seems like a decent human being with good politics has won an election somewhere, but because of the backdrop that victory was won against.

Less than a year ago Evo Morales, of the same Movimiento al Socialismo party as Arce, was ousted from power in a coup supported by the United States and replaced by interim president Jeanine Añez, a far-right zealot whose policies attempted to undo the progress of the Morales years. Morales’ nationalization of Bolivia’s oil and water helped grow the country’s GDP from $9 billion to $42 billion in a decade, lifting millions out of poverty, and his commitment to protecting and advancing the human rights of Bolivia’s indigenous population was historic in scope. Añez immediately set out to sell of Bolivia’s resources to private industry and to terrorize indigenous Bolivians out of public life in a campaign of political and physical violence.

On November 15, the army opened fire on a peaceful demonstration in Cochabamba, killing eight and wounding dozens more. On November 16, a day after the Cochabamba massacre, Áñez issued a decree exempting the police and military from criminal responsibility in operations for “the restoration of order and public stability.” A carte blanche to kill at will, security forces have obliged the directive with increasing cruelty.

But against all odds, Bolivia’s left wing—its socialists, its indigenous people, its young people—not only braved the persecution and repression of an authoritarian government that tried to wage the kind of election fraud that Morales was accused of before his ouster, but crushed that government by such a margin that the ruling party had no choice but to admit defeat on election night.

It’s worth examining why Añez’s coup was supported by the United States in the first place—and not just by the Trump administration, but by a broad coalition of elected officials from both parties, billionaires, and perhaps most glaringly the liberal pundit class. The U.S. is certainly no stranger to meddling in the affairs of Latin American nations that elect socialist leaders; when we talk about that in this country, we tend to credit it to a sort of abstract commitment to principle—“we couldn’t let Communism spread in the West, no matter the cost” and skate past the very material reasons why these coups and assassinations have such a lengthy Wikipedia entry.

All of this modern American interference has its roots in Operation Condor, a campaign of terror, murder, and regime change that took root after World War II, which at times even linked the efforts of the CIA and escaped Nazis. The Chilean example is perhaps the most notorious, a team effort to ruin the popular socialist government of Salvador Allende waged by the neoliberal Chicago School of Economics, the Nixon Administration, and Chilean fascists. That group “made the economy scream,” and then capitalized on the unrest to overthrow Allende and replace him with dictator Augusto Pinochet. The rot spread across the entire region for years.

It has taken decades to fully expose this system, which enabled governments to send death squads on to each other’s territory to kidnap, murder and torture enemies – real or suspected – among their emigrant and exile communities. Condor effectively integrated and expanded the state terror unleashed across South America during the cold war, after successive rightwing military coups, often encouraged by the US, erased democracy across the continent. Condor was the most complex and sophisticated element of a broad phenomenon in which tens of thousands of people across South America were murdered or disappeared by military governments in the 1970s and 80s.

Most Condor victims disappeared for ever. Hundreds were secretly disposed of – some of them tossed into the sea from planes or helicopters after being tied up, shackled to concrete blocks or drugged so that they could barely move.

As I said, our American interests went far beyond simply ideological commitments. Each of these coups, assassinations, etc. was a piece of helping build the economic reach of the United States past our southern borders. The same is true of Bolivia, where, under Añez, Morales’ nationalized gas pipelines became ripe for private selling—changing the price point for customers like the United States. Same as it ever was, whether we’re talking about our interests in gas in Bolivia and Venezuela, or Nestle, or the the United Fruit Company (from which we gained the term “banana republic”).

I find it important to relate all this terrifying history because I think it makes even more stark just how much was risked, and won, in the past few days by the Bolivian people. Regardless of who takes power in the United States after November’s election, you can be sure that they will not let this lie forever—America’s elite never give up, they just bide their time. But for now we have a monument to hope against all odds, proof positive that if you not only run on a platform of giving the people what they need but actually deliver it to them, they will risk life and limb to make sure they can keep things that way. (As opposed to here, where we’re asking people to risk life and limb in 12-hour voting lines on the promise that the guy we want to elect isn’t as bad as the last one.)

About a month ago I got the poet Anne Boyer’s newsletter in my inbox, but I hadn’t read it until, incidentally, the day of the Bolivian elections. In it is that same call to situate our own hopes within this broken and violent world, and to refuse to concede to despair despite the overwhelming odds against things getting better. She writes:

They the state, They the oil companies, They the institutions by which the present arrangement reproduces itself -- these are not the Theys I prefer, not like They the lavender asters in September, or They the clouds, or They the bats who adorn the attic. To leave any of it out: the clouds or the state or the bats or the institutions would, however, be a lie. To write only of an I without a We just because the We we have is not yet sufficient would be a lie, too, because the I of the moment is even shakier than a We -- if the We is a dance party with the ghost of a memory of a promise in it, the I is a daybed with the same.

And yet this is it, this life — the only party we got invited to. Marx told us as much about not getting to make our history under conditions of our choosing.

I appreciate those reminders, that no one gets to choose the conditions under which they try to remake the world, and some people have succeeded anyway; and also that—unreliable as the We can seem, the I is even less certain. And her expansion of pronouns continues:

I am saving my own soul by remembering that even in the grim times, what each of us has is each other. At least there is that You, which is every beloved, which constitutes itself across difference and species and the whole of life…It is also the stranger who any of us might be, and in that the only law is probably love, and that the violation of life anywhere is the violation of life everywhere, and in that no one is free until everyone is, You is what everything in the world is staked on, including yourself.

Brecht, of course, wrote "In the dark times there will be singing / singing about the dark times." And I always want to add, to save my own soul, "just check that you aren't singing a lullaby!" despite how much I someday hope to be singing one in a grove to the dialectical sheep. The other reason for this newsletter, is because some mornings you can't fall back asleep because the force of death keeps on its fatal march, and you open Amiri Baraka and find this:

ANCIENT MUSIC

The main thing

to be against

is Death!

Everything Else

is a

Chump!

The main thing to be against is Death. And to do that well, we have to come to know his many faces, even when they are made in America and deployed elsewhere to do their terrible work. Maybe in doing so we’ll be better prepared to hope and struggle for more.

Talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS: If you liked what you read in this newsletter, why not subscribe? It’s free and always will be.