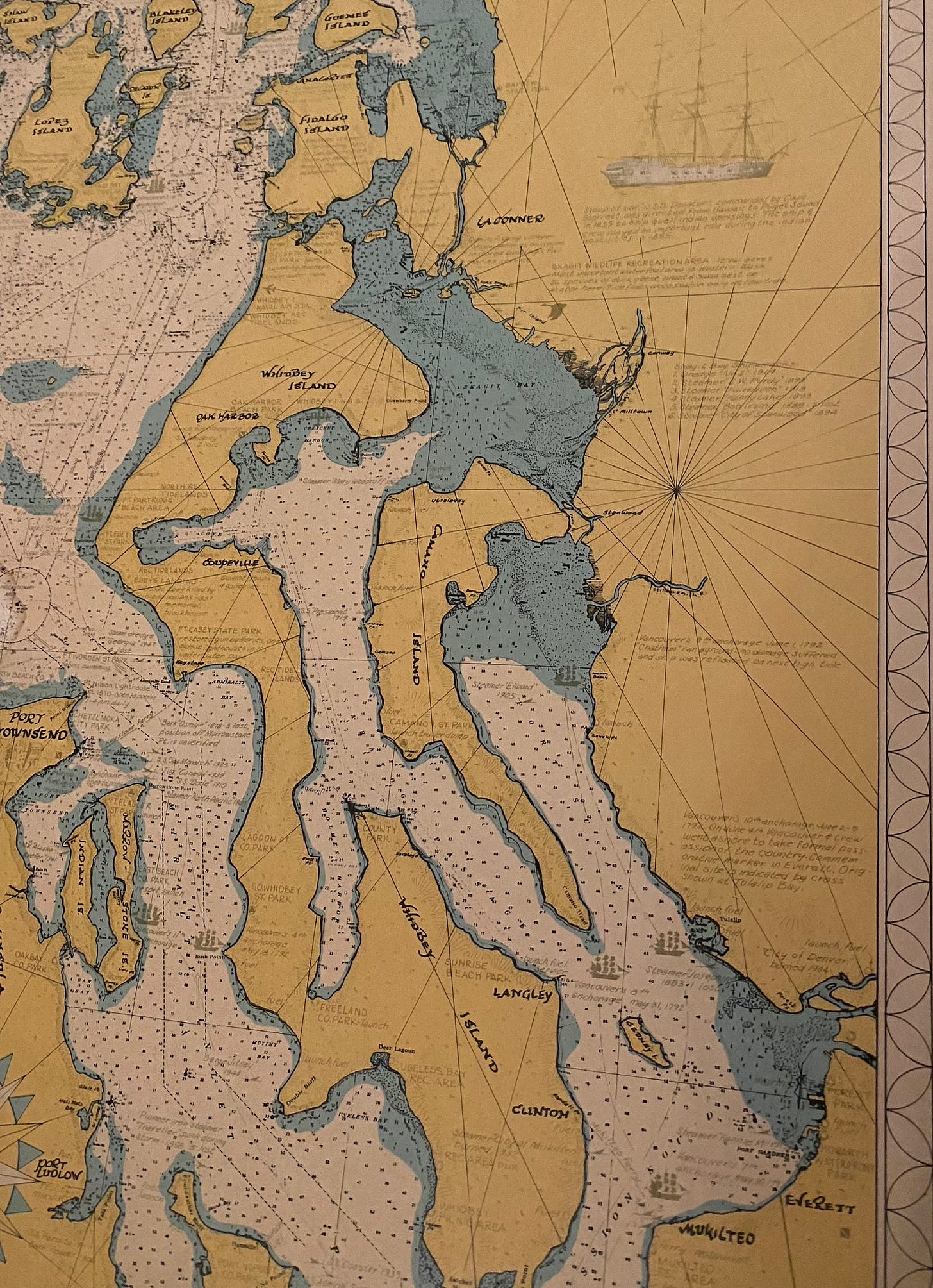

A few weeks ago I wrote at length about the idea that “a word is elegy to what it signifies.” There’s a related aphorism I’ve been dwelling on this week: The map is not the territory.

Like Russell Crowe, I’ve spent a lot of time looking at maps, for purposes both practical and recreational. Ask me to map out what groceries and meals I’ll need for the week and my brain will sound like Charlie Brown’s parents before you’ve finished the question. Ask me to map out some options for a cross-country road trip that takes X number of days and passes through Y states or national parks and only has overnight stays at KOA campgrounds and I will easily (and gladly) lose an entire afternoon in the pursuit.

Of course, doing this in 2-D is the easy part. As anyone who has ever gone anywhere knows, well, the map is not the territory. There are all sorts of things to contend with here in the physical world, things that fundamentally alter the shape of a trip: a freak snowstorm in Wyoming, a traffic snarl outside of Buffalo, an unholy bathroom situation at an Idaho rest stop. A roadside diner appearing like a desert mirage during a difficult and hungry hour. A roadkill red fox that makes you spiral thinking of mortality and the endings of things. The omnipresence of aggressive state troopers on the eastern seaboard and their complete absence on the plains.

No, the map is not the territory. But it does provide a usefully representative microcosm of reality, and the thrill of all the schemes and plans you can project onto it.

Our ability to create and, crucually, recognize visual representations of real-world phenomena has other applications, too. Pattern recognition is a core component of being able to make connections, learn from mistakes, and avoid danger. And it’s not just us that do it: human children as young as two can identify visual patterns and make connections, but so can crows and ravens, as can dolphins, apes, koalas, and many other animals.

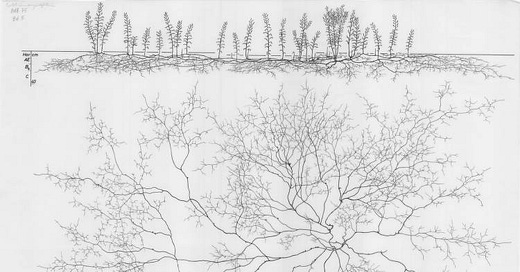

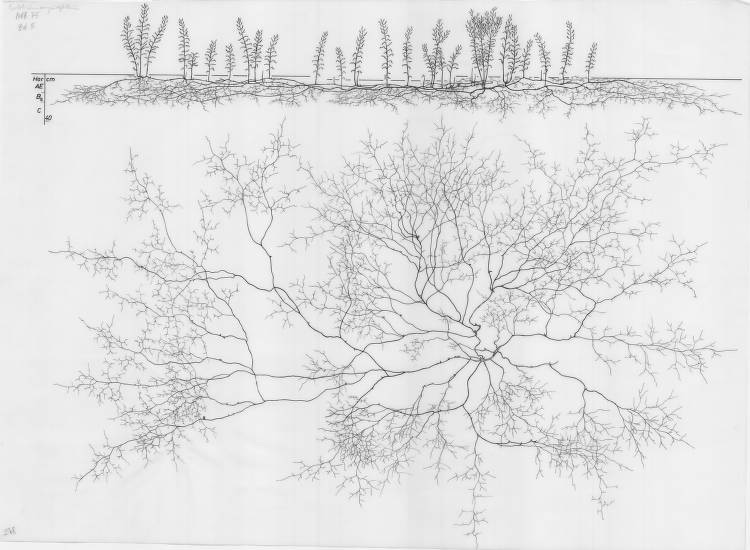

Still, an observation being facile doesn’t make it untrue. So I am moved by the similarities between the systems that sustain all life here on earth. The way the paths of rivers and watersheds so closely resemble the filigree of blood vessels in the body, the geometric spreading of tree branches, the tangled synaptic web of fungal hyphae linking those trees together below ground. The vermiculate topography of ranges, peaks, and passes might well be replicated on the back of a trout. The human nervous system in isolation resembles nothing so much as the deep roots of prairie grasses and wildflowers.1

While this type of visual conclusion can certainly be taken too far (see the very scientific image below), I still find it instructive. Especially at this time of year when all things are rushing into life. Snows are melting, flowers are pushing up through the damp ground, the winter songs of the cardinals are making way for the spring songs of the robins. There are familiar patterns not just in space, but in time, and these too can ground us as a map does, orienting us toward the green piece of the year in which suddenly we find ourselves after the season of whites and grays.

A few Marches ago, at the very beginning of COVID-19, I drove out to the woods and hiked up to a mostly-frozen lake off of I-90. Sitting in a snow cave of someone else’s making and wondering if everything I ever knew was going to fall apart, I wrote a poem, part of which is as follows:

The trickle of snowmelt on the overhanging branch becomes a finger of the creek. In everything there is a quickening. The sun warms the heavy forest and carries its promise of spring, and the trees and small animals burst toward life even as they creep closer to death. I am a contradiction, too. I have heard that when one dies there is a flashing before the eyes of all moments one has lived. Carving off half and half again all the way to the ending. But of course you can’t actually reach the end this way. In this way nothing ever really dies. In some forests I have lusted for the whole world. Out of control, a lunatic in the old sense even though the sun was out. As a child I would bury myself in the earth, I would kiss the grass, I would run my fingers along the soft furrows of the land until I thought my being might dissolve.

This time of year does tend to make me go a little feral, wondering at all the life apparent everywhere after so long without it showing itself. At no point am I more attuned to these patterns and connections than I am in the early spring. I find myself rushing headlong into this season of growth and life, ready to make reckless plans, ready to confuse the map with the territory all over again.

It’s good to be alive, isn’t it? Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

Like Epilobium angustifolium, fireweed, whose root system graces the top of this newsletter.

Not sure if you have seen this article from the Bitter Southerner, but given today's post, seems like something you would enjoy.

https://bittersoutherner.com/feature/2023/paper-trails-pisgah-map-company-asheville

Have a great weekend!