The Shape Of The Land Testifies

The woods and mountains: A recommendation

Note: I wrote much of this piece earlier this year, intended to be the first in a series of travel essays about places that are important to me. Depending on the reactions to this one I may still do that. Either way it felt important to get this one—about the Olympic mountains and national forest—out in the world before the end of the year. Let me know if you’d like to see more of this kind of thing.

Along a certain trail in the Olympic peninsula there exists a small, lush grotto so pristine and perfect that it might well be a portal to some fairy realm. The steady waterfall behind the boulders creates a constant spray in which a rainbow kaleidoscope dances, filling the air above a carpet of ferns. The water that pools below is a bright blue coin in the summer sun.

I will not tell you where, specifically, such a grotto exists. It is along a trail that is not difficult to access but the hike to the grotto is a taxing one. In fact you could miss it entirely if you’re not looking for it, as people are usually using the trail to reach the terminus, which has its own separate appeal. (What that terminus is I also cannot tell you, for obvious reasons.)

The Olympic Mountains contain such majestic sights that I think it’s important to remember to look around at the small wonders every so often. The grotto, of course, but also the broad ferns, the shiny beetles, the mammals of the undergrowth going about their daily dramas. The streams that trickle out of sight, whose sounds meld so completely with the silence of the old growth that it is often difficult to notice when you have begun, and ceased, to hear anything at all.

When people think of Washington’s mountains, the volcanoes almost certainly come first to mind. Mount St. Helens erupted 40 years ago this year, world news from a sleepy, rural corner of the state. Harry Truman, a curmudgeonly local character sandwiched between the president and the sheriff of Twin Peaks in the annals of that name, famously died on the slopes after refusing to evacuate.

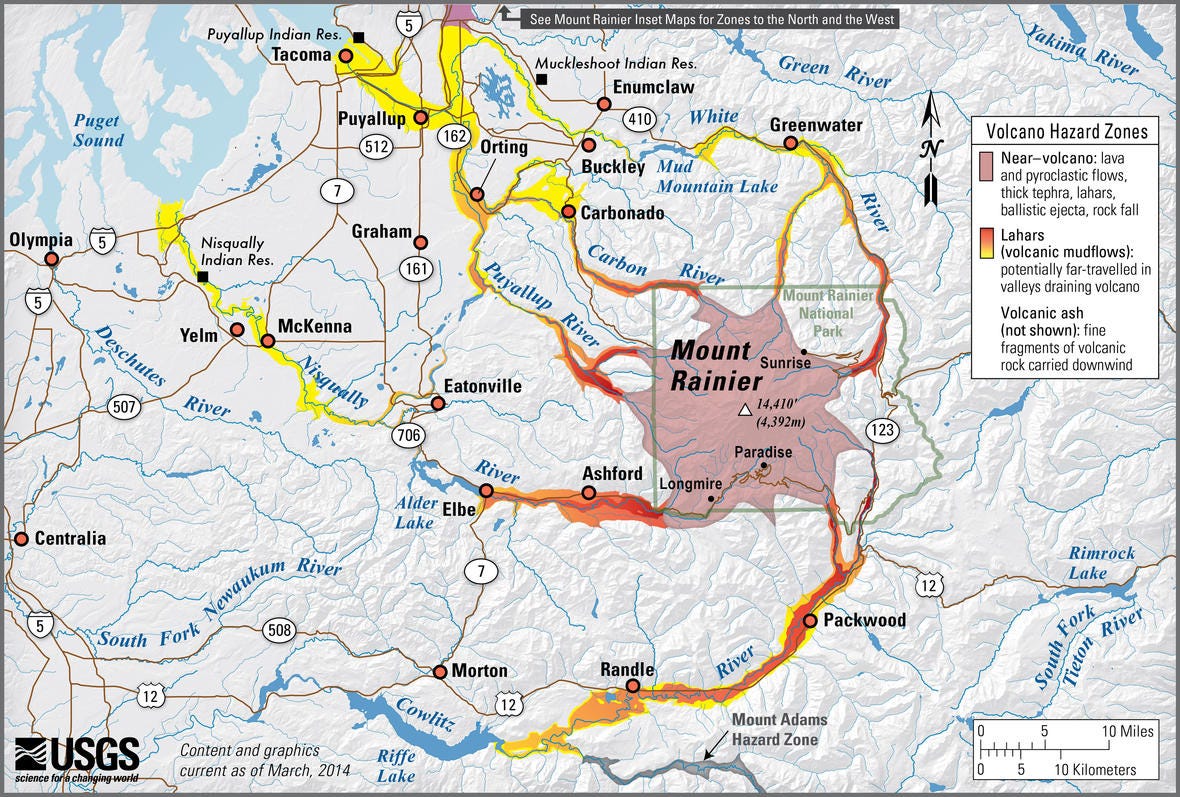

Then there’s Mount Rainier, Tahoma, whose last major eruptive period 5,600 years ago created such massive mud flows that several counties’ worth of land was permanently transformed. It’s on the “Decade Volcanoes” list, an innocuous name for the 16 peaks that scientists are keeping an eye on because of the combination of their massive eruption potential and their proximity to major metropolitan areas. Were Rainier to blow its top again, the lahars, volcanic mudflows, would take the paths of least resistance—the river valleys surrounding the mountain—and overwhelm cities and towns as far away as Tacoma. Life in Western Washington would be permanently and dramatically altered.

The Olympic Mountains contain no such potential for chaos. They were formed in the imperceptibly slow, unsexy process of pressure and time, the pushing and grinding of plates of such mass that eventually something had to give. Between 12 and 20 million years ago the plates at the western edge of Washington met with force enough to drive the seafloor several thousand feet upward. This permanently raised the land in a spine of coast that concurrently drove the earth downward on the eastern side, creating a massive oceanic strait called Juan de Fuca. (Despite what you would be forgiven for assuming, de Fuca was Greek, not Spanish. And that’s if he even existed at all, which is a matter of some historical dispute, as is whether he ever reached the strait that now bears his name, as is also claimed.)

The scale of geological time is frankly so large as to be beyond my actual comprehension. Humans emerged as a species a little over 300,000 years ago, which is roughly 1/65 as as far into the past as the formation of these mountains. 300,000 years of evolution and conditioning still have not served to create a brain—at least in my case—capable of reckoning with such a scale.

(I was sort of shocked to read recently that despite being around for 300,000 years, we’ve only been writing things down for about 5,500. That means 97% of all human history is lost unless it can be presumed from the fossil record or, in rare cases, preserved by oral tradition to a degree that is only startling to those of us narrow enough to believe that our ways are the only ways.)

The mind boggles at the passage of a single lifetime. So we are perhaps ill-equipped to reckon with all this. But we must try!

The archaeological record tells us that 8,000 years before the advent of written language on the other side of the world, the people of the Olympic forest were hunting the Manis mastodon with bone-tipped weapons. Elsewhere on the peninsula, in the intervening millennia, the indigenous Makah built a society sustained by whaling and sealing, while other peoples aimed for slightly smaller prey in the rivers and forests. Despite reaching the austere Pacific coast, the land that is now Olympic National Park contains a multitide of biomes: a temperate rainforest, thousands of acres of old growth, ancient rivers, and the mountains that rise from sea level to tower above it all.

To be astonished that such diversity of terrain and culture and fauna could exist in a single American state is to forget the lateness with which state boundaries were prescribed. People on the east coast often underestimate the scale of things out west; in the time it takes to drive from the top of Washington to the Oregon border you could drive through four states in the mid-Atlantic.

With that scale and that ancient history in mind we’ll zoom in once more. Within the Olympics sits a pair of peaks called The Brothers, whose twin outline is tantalizingly visible from Seattle on clear days. Last summer I summitted South Brother with two friends, on my second try in two years, and here again we are forced to reckon with the passage of time—one of them I’ve known since middle school in upstate New York, the other I’ve known since my sophomore year of college in Ohio. And at the time of that trip all three of us lived along the Puget Sound at the urban edge of all this vast and ancient wilderness.

You can reach the summit of South Brother without traditional climbing equipment, which is to say without ropes or technical know-how. You do still need a helmet and the ability to keep your eyes pointed up instead of down as the world falls away beneath you. It’s something more than hiking but less than pure mountaineering. Trip reports call the journey to the summit a scramble, but that doesn’t feel quite right either. The last few dozen feet up bare spires of rock qualify as such, but the long 45° snowfield that you have to piston your way up with crampons and an ice axe prior to that step puts the experience beyond that simple characterization, too. The taxonomy gets more complicated even as the views and choices available to one grow simpler.

On clear days you can see all the way back to Seattle from the summit. Other days—like the day we reached it—the peak is wreathed in clouds, covering everything with a slick mist and limiting visibility to a few dozen feet. Still, it’s hard to feel disappointed when you’ve bagged a peak, especially when doing so has entailed an hours-long slog up a forested burn and over precarious bridges of melting snow.

We were not alone at the summit. On the surrounding rocks a whole family of mountain goats investigated our presence as they went about their strange, wild day. Though better suited to the terrain than us—which they made obvious with each careless step across rock faces that would have taken our lives—they were, technically, more alien to the region. Mountain goats aren’t native to the Olympics, and arrived far more recently than humans did, the product of a relocation effort from their home in the Cascade range a few decades ago. In fact their alien presence has become something of a problem; they like the place so well that they’ve begun posing an environmental threat as they breed and range out. (Their cravings for salt also mean they pose a threat to humans, who they will aggressively pursue for sweat and urine.) Accordingly, beginning in the summer of 2020 the state of Washington began a program to airlift out as many of the peninsula’s goats as possible and relocate them in their ancestral homes in the Cascades. Those that they couldn’t airlift, which they estimated to be about half of the 725 goats in the region, met a grim fate. Per the National Park Service—and no I am not making this up:

Olympic National Park has recruited 21 groups of skilled volunteers to assist with the ground-based lethal removal of the remaining non-native mountain goats from the park this fall.

There’s something so perfectly human about talking this way—like a cop to a reporter—about a situation both so morbid and absurd. I’m picturing a press conference given by a man with a pack-of-hotdogs neck and a blistering Chicago accent saying that. After tactically ascertaining da perimeter of da subject area, da targets were, regrettably, removed via ground-based lethal strategies. Rest in peace to the ones that didn’t make it. My own experiences in the Olympics have been indelibly marked by the goats, and it will be strange to return to those peaks knowing there won’t be any left to see.

Coming down from the summit of South Brother last year, our little party stopped at the edge of the final snowfield to triumphantly remove our crampons for the last time. Whether or not the goats had something to do with what happened to us next, I can’t say. But they’re on the list of suspects. As we sat there laughing about the little stupid things that get magnified into grand jokes when you’ve just finished an arduous mountain adventure, everything went quiet for a moment and then we heard sounds of clattering and cracking from up above us. We took one look at each other and then ducked with arms behind our heads—and an instant later a rock the size of an office chair hit the snow some twenty feet away at the speed of a car crash.

These mountains may not be volcanic, but don’t mistake that to mean they have no violence in them.

The Olympics are home to the loneliest sound in the world. At least in my estimation. The story of the elk, who make that sound, is—like the goats—a story of retreat and revival. Endemic to Washington, first appearing around 10,000 years ago, elk were hunted and driven out of the area so thoroughly that they were gone by the 1850s.

But they have returned—some 60,000 of them now call Washington home. I have heard their bugling in the fog and the rain in the Olympic forest. It can take the heart right out of you, I swear. (Listen to the sounds of that video and then imagine those notes held for impossible, devastating intervals, crashing off of the walls of a mountain valley. It’s enough to make you believe in love and ghosts and all sorts of other things. Ancient and sagacious forest magic, maybe.)

I have written before about the elk, and about the strange tension that exists between my awe of them and my willingness to eat them when the opportunity presents itself. I have not gotten any closer to solving that particular dilemma. But I take great comfort in knowing that they are back and filling the forest with their majesty.

During and after my trips to the Olympics I have written thousands and thousands of words trying to unpack and explain just what they do to me. As is so often the case the more complicated explanations are inferior to the simple ones: big mountains, wide rivers. Ancient trees growing as though young. Young animals growing with ancient spirits. The Olympic peninsula is so bountiful that all else seems to shrink around it—cares, concerns, troubles.

On my second trip to South Brother, the successful one, I unwound in my hammock at climber’s camp with Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, rigging up a tarp between trees to keep the pages dry as the nourishing rain came down. I came across a passage that could not have been more perfect for the quiet grove of cedars and other towering trees where I perched. It reads:

The dark limbs of the trees reached out over his head, holding their many wide green hands above him. Awe came into him. He knew himself blessed though he had not asked for blessing.

May we all find such places.

PS- Signed copies of my book about thru-hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, A Good Place For Maniacs, are 20% off through this Friday, 12/5. Hit the button below to find the order form!

Yes.