There Are Others Born With The Wisdom To Know That Nothing Lasts

It breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart.

Like people in a lot of countries, I grew up on baseball.

I didn’t care about the sport in any professional sense for a long time; my interest extended no further than my tee-ball and “coach pitch” games. Along with my final season of coach pitch came the beginning of my understanding that not all kids are created equal, athletically: that first real stratification between kids who had Potential and kids who were just kids. I was in the latter category, obviously. I was still getting thrown to underhand by well-meaning dads while other kids in my grade were playing with older boys who pitched to each other. (Although no one I knew in the former category ever went pro, so part of me suspects they went through a whole lot of grief for nothing.)

These days what I really care about is baseball on the radio. A few years ago, in an effort to restore the frenzied Red Sox fandom of my teenage years, I downloaded an app that lets you listen to the home radio broadcast of every team in the majors. I rarely have time to sit down and watch a whole baseball game, I reasoned, but I could always have the radio on in the background while I do other stuff.

In between innings, this has brought with it the bizarre experience of hearing the minutiae of life elsewhere—the names of grocery stores I don’t recognize, jingles for HVAC repair firms and car dealerships, regional inside jokes, and so on. It is some small comfort that despite the omnipresent pressure toward homogeneity in this country you can detect different shades of life just by turning on the radio. The Red Sox guys seem to genuinely love one of their advertisers, Shaw’s Market, trading barbs about how many times a day the other one goes and which donuts at the bakery counter they’re suckers for. (Even a crusty anti-capitalist can chuckle at that.)

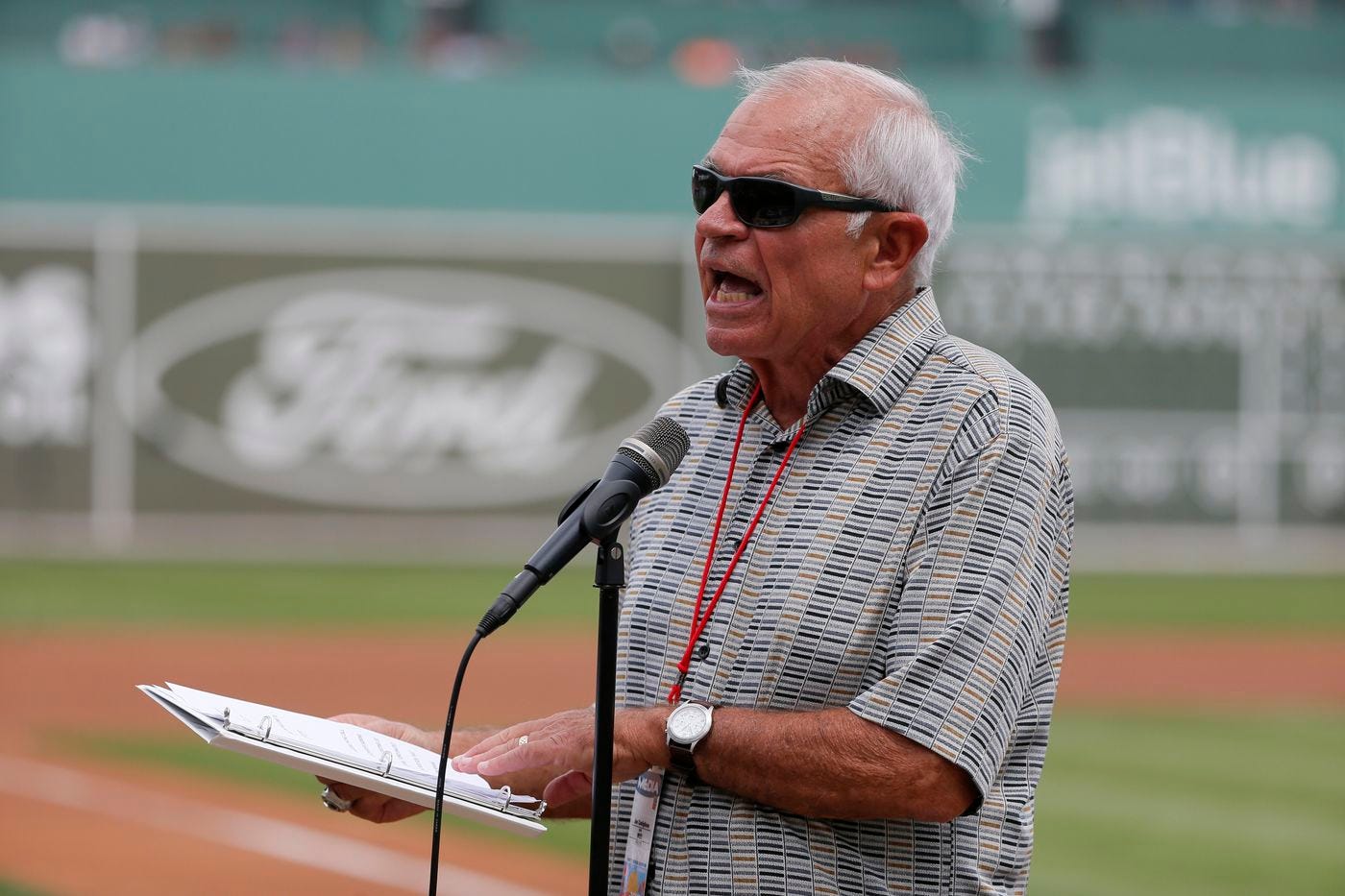

Speaking of the Red Sox: if I told you that the main radio commentator was an old New England guy named “Joe Castiglione,” what kind of person would you picture? Congratulations, you probably pictured him:

Perhaps what’s best about baseball, however it’s consumed, is that (carrying as it does such an absurdly long season) for much of the year you can just try again tomorrow. There’s comfort in that, a comfort that college football fans or soccer fans could never experience unless they’re the long-suffering type with no hope anyway. Miss a few innings here or there, sleep through a game, have a busy week—well, there’s still a lot of baseball to be played. Some of this newsletter was written while I was half-paying attention to a Sox-Orioles game. Even the All Star break at the season’s halfway point feels more like cresting a gentle hill than anything.

For most of human history—as Ken Layne described it in another excellent recent episode of Desert Oracle Radio—storytellers weren’t just entertainers, they were doctors and healers. In the past and present of any people, the stories are what bring understanding and closure and a place to rest. Radio baseball accomplishes the same thing for me. Old men with pleasant voices omnisciently narrating a series of events I can’t see, weaving in tales of heroes past. There is nothing better than a baseball nap, in my book: zoning in and out of consciousness as this warm bath of voices washes over you, their timbre tuned perfectly to match the sound of nearby lawnmowers, sprinklers, bees.

Castiglione might agree with Layne:

I think there's so much tradition, that you have to know the history of the game. And that's what I mean by lifetime preparation…The other key is [to] learn how to be a good storyteller, because you have to fill in between the pitches. And to be a good storyteller — to pick up stories — you have to be a good listener. When I go to the ballpark and I'm on the field, my job is to listen to what people say and then, you know, file it in my brain, or take notes, or whatever, so that I can tell stories…

Another such storyteller was commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti—father of actor Paul—who served in baseball’s top spot for just five months before dying of a heart attack. Giamatti, as both a man of literature and a pre-broken-curse Red Sox fan, was uniquely positioned to describe the romance and heartbreak and meaning of baseball. (Giamatti, too, believed it to be a “radio game.”)

Summer died in New England and like rain sliding off a roof, the crowd slipped out of Fenway, quickly, with only a steady murmur of concern for the drive ahead remaining of the roar. Mutability had turned the seasons and translated hope to memory once again. And, once again, she had used baseball, our best invention to stay change, to bring change on.

That is why it breaks my heart, that game--not because in New York they could win because Boston lost; in that, there is a rough justice, and a reminder to the Yankees of how slight and fragile are the circumstances that exalt one group of human beings over another. It breaks my heart because it was meant to, because it was meant to foster in me again the illusion that there was something abiding, some pattern and some impulse that could come together to make a reality that would resist the corrosion; and because, after it had fostered again that most hungered-for illusion, the game was meant to stop, and betray precisely what it promised.

Of course, there are those who learn after the first few times. They grow out of sports. And there are others who were born with the wisdom to know that nothing lasts. These are the truly tough among us, the ones who can live without illusion, or without even the hope of illusion. I am not that grown-up or up-to-date. I am a simpler creature, tied to more primitive patterns and cycles. I need to think something lasts forever, and it might as well be that state of being that is a game; it might as well be that, in a green field, in the sun.

It’s important—politically, spiritually, personally—not to lose all of one’s illusions too quickly. That way lies total despair, which many people mistake for honest virtue. The morally important ones need to go, obviously, the kinds of illusions that allow people to ignore world-historic suffering under the spell of words like Freedom and Justice. But a total collapse of all illusions at once can’t be good for the soul. Baseball, the way Giamatti describes it, serves an important function, recreating annually just enough of the magic to keep us healthy. That the tide will always come in is no reason not to build sandcastles, you know?

Giamatti was certainly not the only person qualified to write about such things, and a few years later the author Tobias Wolff published the short story “Bullet in the Brain,” which is about all sorts of things—memory, regret, aging, cynicism, alienation. But the story ends with baseball, and a peek at the lasting impact of its routines and rhythms on the American psyche.

“Shortstop,” the boy says. “Short's the best position they is.” Anders turns and looks at him. He wants to hear Coyle's cousin repeat what he's just said, though he knows better than to ask. The others will think he's being a jerk, ragging the kid for his grammar. But that isn't it, not at all—it's that Anders is strangely roused, elated, by those final two words, their pure unexpectedness and their music. He takes the field in a trance, repeating them to himself.

The bullet is already in the brain; it won't be outrun forever, or charmed to a halt. In the end it will do its work and leave the troubled skull behind, dragging its comet's tail of memory and hope and talent and love into the marble hall of commerce. That can't be helped. But for now Anders can still make time. Time for the shadows to lengthen on the grass, time for the tethered dog to bark at the flying ball, time for the boy in right field to smack his sweat-blackened mitt and softly chant, They is, they is, they is.

Whether you care about baseball or not I can’t recommend highly enough that you go read the Wolff story and read/listen to Giamatti’s essay, both of which have much more to say about the human condition than I could hope to do justice to in a newsletter.

If it isn’t baseball, I’d be curious to hear from you—in the comments here, in a reply email, on Twitter, wherever—what it is for you that restores those necessary illusions, that takes up the long summer evenings in the deep recesses of your brain. We are creatures of longing and memory and I think it’s worth reminding ourselves of that every so often.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be. If you want to support Tabs Open, you can also share this post or buy a sticker.

"People ask me what I do in winter when there's no baseball. I'll tell you what I do. I stare out the window and wait for spring." - Rogers Hornsby