Last week I pulled my groin playing ultimate frisbee. Such is the price of existing in a body that’s older than thirty, especially when you task that body with trying to outrun people younger and more fit than you all over a turf field.

That same day my dog tweaked her back leg doing god-knows-what. So we spent two days together basically just hobbling around the house, trying to move as little as possible while we nursed our own nagging pains. For her, that meant her usual long hours of walking were cut down to a few minutes outside to sniff the air and use the bathroom. For me, that meant missing our second frisbee game of the week after my injury took me out for the final two decisive (losing) points of the first.

It’s funny, how dramatically pain shrinks our worlds. Pain makes us small. If I’ve learned anything in my time on this earth, it’s that. When I’m sick, I often lay in bed and wonder how anyone is up and about doing things, living their lives, expending energy. Being hurt makes me feel the same way. How is anyone out there running around, enjoying themselves, functioning at all, if I can’t be?

Obviously this is not limited to physical pain, either. To be alive in America in this day and age is to be crisscrossed with psychic scars. We are overworked and undernourished, overprescribed and under-cared-for. We are more aware of the world’s horrors than at any other point in our history.1 And our future is being dismantled right in front of us as our leaders do nothing more than ask for money and votes. By virtue of wealth or genetics or luck some people cope and endure better than others, but there is basically no way to be unaffected by our profoundly devastating and alienating world.

No one wants to be this way. We are scared of pain because, obviously, being in pain sucks, but I think it also comes from understanding on some level that our pain does shrink us, does make us more selfish and less readily lovable. We do not want the people we care about to cast us off or move on without us; we are all so alienated from each other and our communities of care have so eroded that the prospect of losing any support you do have is rightly terrifying. There’s this spiraling effect where being in pain makes us act in a way that separates us from our communities, and that separation causes more pain, which in turn separates us further, and on and on and on.

It is this fear of pain that monsters like the Sackler family exploit to unleash their generational plagues on suffering people. It is this fear of pain that monsters like our legislators exploit to turn our ire on one another as they rob us blind and hoover our wealth upward to themselves and their masters. It is this fear of pain that the truly depraved seek to sow and maximize with their weapons of war in our public spaces.

And of course, building or rebuilding the kinds of communities that can insulate people against their pain is profoundly difficult, in part because so many people are in pain. To have close friends or biological family or chosen family or comrades is to take part in a constant negotiation with oneself: how much bullshit do I allow or absorb or brush off from people I know are hurting, and how much do I not? Which relationships are worth holding onto through the worst times, and which are so unhealthy as to be allowed to wither, even when I know that pain is to blame for the other person’s behavior? There are no prescriptions for such negotiations. I can’t tell anyone how to manage this in their own lives. We all have to do our human best to figure it out.

Something that has helped reorient me lately is this bit from George Saunders’ Congratulations, By The Way, which I came across in The Small Bow:

What I regret most in my life are failures of kindness.

Those moments when another human being was there, in front of me, suffering, and I responded … sensibly. Reservedly. Mildly.

Or, to look at it from the other end of the telescope: Who, in your life, do you remember most fondly, with the most undeniable feelings of warmth?

Those who were kindest to you, I bet.

It's a little facile, maybe, and certainly hard to implement, but I'd say, as a goal in life, you could do worse than: Try to be kinder.

This is all very sensible advice, difficult as it may be to follow in any given moment. What I appreciate about it is that there is no demand or directive, no pablum about needing to be kind no matter what, which is obviously a recipe for allowing all sorts of horrors into one’s life. It simply sets us a north star to navigate by: try to be kinder.

If that feels hard, which it probably does, know that it feels hard for a good reason. This sermon from Reverend Mclean in A River Runs Through It has stuck with me for years because it encapsulates so many of the difficult emotional relationships in my own life:

Each one of us here today will at one time in our lives look upon a loved one who is in need and ask the same question: We are willing to help, Lord, but what, if anything, is needed? For it is true we can seldom help those closest to us. Either we don't know what part of ourselves to give or, more often than not, the part we have to give is not wanted. And so it is those we live with and should know who elude us. But we can still love them - we can love completely without complete understanding.

This sermon makes a tidy companion to the Saunders piece above, although it takes kindness into the realm of the spiritual, and describes it as love instead. Pain doesn’t just make us smaller, it makes us less rational, which means that when we’re in that state we may not even be able to know or accept the kind of help we need. If we’re on the other side, then, our options are to stop offering help or to persevere with all the love and kindness we can muster. I have certainly chosen the former option plenty of times in my life and some of those times it was even the right choice. But rarely have I regretted the times when I chose the latter.2

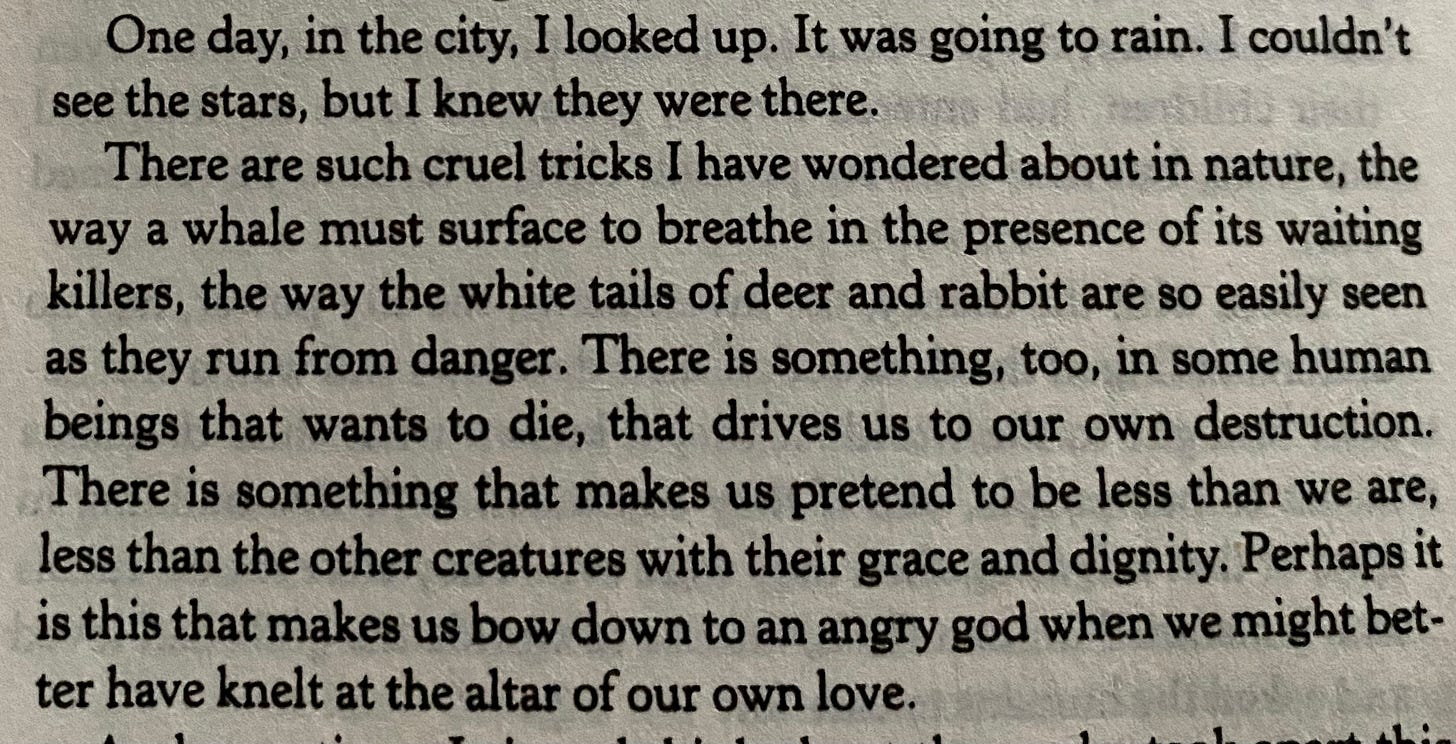

In her novel Solar Storms, Linda Hogan writes:

I dream of building a world in which we learn to kneel at the altar of our own love. But I learned a long time ago that you can’t sit there hoping for that world to be built. You have to pick up your tools, too, understanding that doing so requires not just dealing with, but learning to love, other people in all their messy complexity and pain. If we don’t—if we let our aversion to pain win out—then we, like the nihilists, will have created a self-fulfilling prophecy from which there is no return.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

As I sit writing this, we are hours removed from our most recent mass gun murder, this one at a 4th of July parade in Illinois. Hard to imagine a more fitting American news story.

A few months ago a student of mine failed the GED math test, his last one. He came in the next day and told me that I should quit my job because I was clearly so terrible at it that I was incapable of helping anyone. Choosing to react with kindness in that moment ended up leading to one of my best moments as a teacher: two weeks ago I got to hug him and watch him walk across the stage at graduation.

Wow, that second footnote.

Very Nice.....Very Nice