There are so many things that I mean to write down that many of them just slide away into nothingness. I’ve been at this long enough to know that the best and truest ideas will usually return when I need them, but the little details and anecdotes and images have a tendency to disappear if I don’t get them down on paper.

Just now, sitting down to figure out what to write about, one of these latter types came to me: Three ravens perched on a pickup truck in Kellogg, Idaho. I’d meant to write that phrase down three weeks ago and forgot until just a minute ago. On the first morning of our recent road trip I took my dog for a walk along the street in that town, where we’d stayed the night, and in front of one house there they were. My attachment to the meaningful symbols in my life makes it hard to tell the full truth of these things sometimes but I feel compelled to tell you that one raven was really just sitting there and the other two were feasting from a garbage bag in the bed of the pickup. You’d like more poignance from the things you ascribe wonder and religiosity to—corvids, in my case—but there it is. I have no bigger idea to draw a line to from that picture. Sometimes a bird eating trash is just a bird eating trash.

It being hard to tell the truth of these things publicly does make me feel like getting things down in some way, even privately, is an important act. I’m rereading Jon Lee Anderson’s seminal biography of Che Guevara right now (Che: A Revolutionary Life) and I have been struck by how many details of Guevara’s life and the shaping of his ideology we only know because he wrote them down in his diaries from a very young age. With access to both those private diaries and the officially sanctioned materials that Che published in Cuba after the revolution, Anderson paints a thorough, and human, portrait of a man who has been dehumanized by sixty-odd years of mythmaking, which inevitably happens to any figure who becomes so internationally important.

It is vain, perhaps, to think that there will be a public appetite for any of our stories to be told in full a half-century from now. But one need not hope for fame or glory to want to put things down for posterity. And I think we are all much too trusting, here in this digital age, that any of it that we put exclusively on the internet will last. Look no further than HBO Max’s recent overnight deletion of 36 titles from its catalog, including 20 originals. Those aren’t just “shows” and “movies;” they’re the result of years of creative work, years of ideas and dreams brought to fruition by artists. And now even those artists will have to find ways to stream their own work illegally if they ever want to watch it again.

It’s a dramatic example, no doubt—how many people do you know who have their artistic work hosted on a major streaming platform?—but I still find it instructive. If you don’t own the platform, the stuff you put on the platform is only “yours” for as long as the owner allows it to be. Owning your own domain name is a great start if you’re a person who does any kind of creative work, even if you just want somewhere to journal. But none of us owns the internet, and like all goods that should be public it is currently being consolidated into fewer and fewer private hands without any of our say-so. (Unless Jack Dorsey or Mark Zuckerberg is subscribing to this newsletter under a burner email address, in which case may I please have $100,000.)

In fact my real advice, advice I need to do a better job of following, is to back up anything you care about in a physical form.1 I have nothing resembling technological skills and I’m sure folks who do could tell you some more secure ways to save copies of things to your cloud and computer and whatever else. But it never hurts to have a failsafe. Do you have a lot of faith that the world, as currently constructed, is going to last a particularly long time? I know I don’t!

As Jonathan Zittrain writes in The Atlantic:

Before today’s internet, the primary way to preserve something for the ages was to consign it to writing—first on stone, then parchment, then papyrus, then 20-pound acid-free paper, then a tape drive, floppy disk, or hard-drive platter—and store the result in a temple or library: a building designed to guard it against rot, theft, war, and natural disaster. This approach has facilitated preservation of some material for thousands of years…

These buildings didn’t run themselves, and they weren’t mere warehouses. They were staffed with clergy and then librarians, who fostered a culture of preservation and its many elaborate practices, so precious documents would be both safeguarded and made accessible at scale—certainly physically, and, as important, through careful indexing, so an inquiring mind could be paired with whatever a library had that might slake that thirst.

As a Marxist I’m embarrassed to admit that second paragraph really struck me. I hadn’t considered that angle as I rode this train of thought: that the preservation of knowledge is itself arduous and specialized labor, and like all labor whose worth can’t be measured in profits, it has been devalued by the development of a society that can prioritize nothing else.

I used to think it was corny that my mom would occasionally print out my blog posts to read and save, but now I realize that unless I put in some work on my own behalf, those pages might someday be the last surviving versions of those ideas, of that version of me. That’s a sobering thought for someone who has spent so much time writing on the internet. It’s also really nice to feel loved like that. Like I’ve got a personal archivist who would care about my work whether or not it was any good.

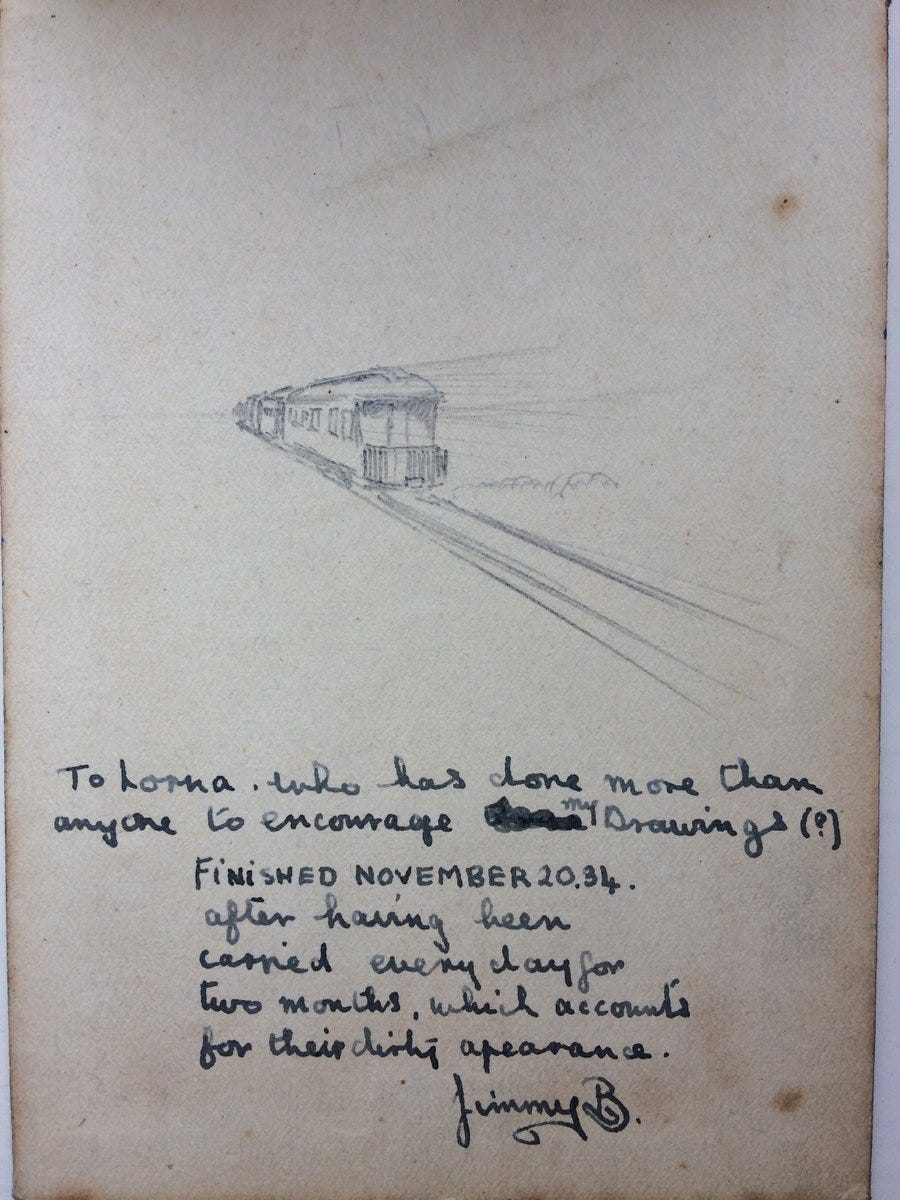

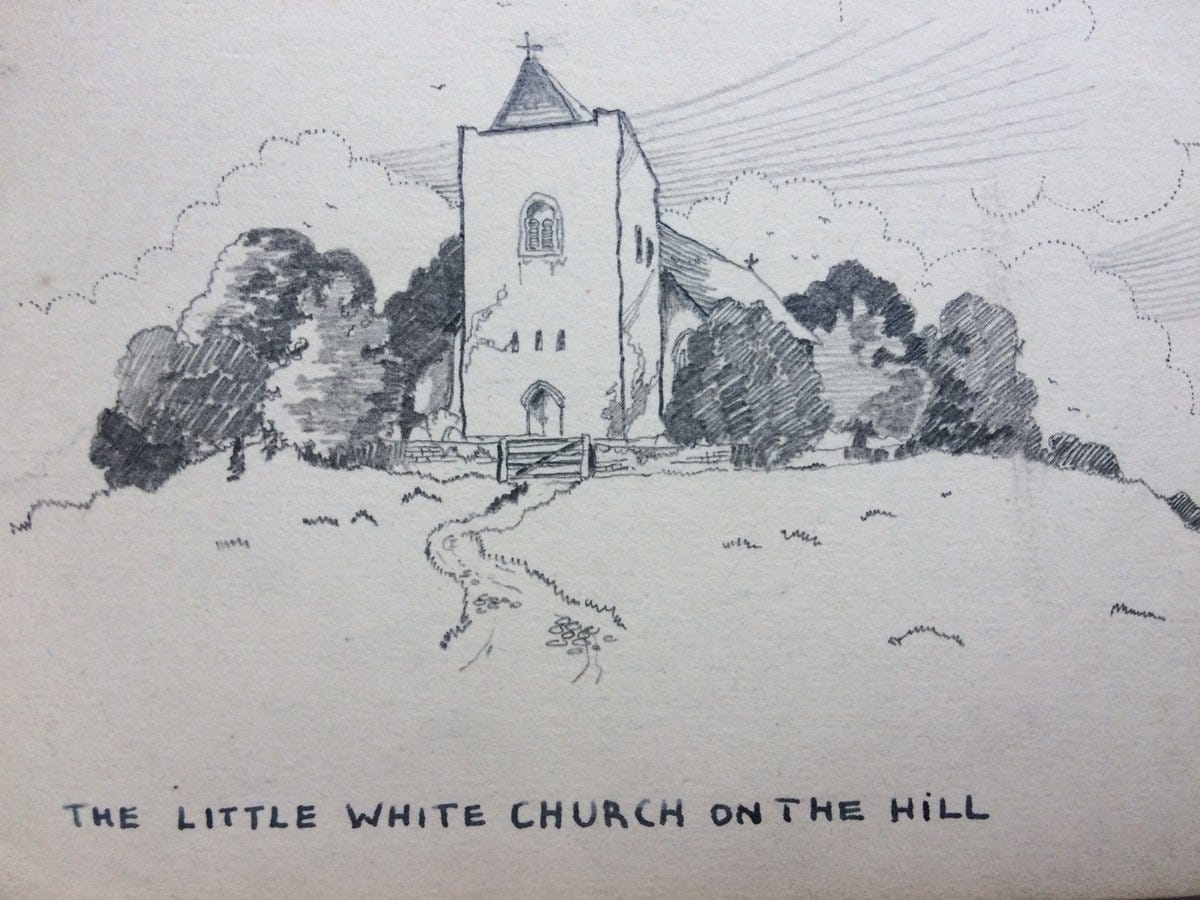

That thread is a perfect example of what I’m talking about.2 Jimmy-the-Boyfriend was not a famous artist, but he clearly worked at his craft, and valued both his own work and Grandma Seaside enough to archive those drawings and give them to someone who he thought would care for them. He was right, and now almost a century later thousands of other people can enjoy them, too, through a medium he could never have imagined. I think that's a beautiful thing. An aspirational one, too. May we all love our own work enough to preserve it like this.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

I’ve started using the PrintFriendly browser extension to create neat PDFs of the stuff I write, but as I don’t have a printer, I haven’t gotten around to that part of the process yet.

In more ways than one, really. If that person ever deletes their Twitter account or gets banned from Twitter or Substack just outlives Twitter, there will be a weird empty space in this newsletter and anyone going back to read it will have to contend with some missing context.

Man this hits close to home again, like squarely on my front porch.

The work of the archivist is the hardest and most important in the long term and the easiest to cut in the short term. And if it lives on the internet, it is destined to die. Why do I have all these screenshots and pdfs cluttering the corners of my hard drive? I don't know but they can all disappear from their source tomorrow. The same goes for all my rambling thoughts and feelings and observations and random little projects that could just as easily disappear from the earth when I go.

Take pictures, write something, make something, and leave something behind. Buy books and music and movies, all the things you value because they'll disappear as soon as it becomes profitable to make them disappear.