As the summer draws to a close—I start my final year of graduate school on Monday, as well as a new year of teaching a required freshman composition course at that same school—I am thinking about the fact that this was the first summer in several years that my wife, dog, and I did not embark on a cross-country road trip. We were all grateful for the break, I think; a journey of that size and length usually has as many challenges as it has rewards, and while that’s always a worthwhile tradeoff it creates its own particular kind of exhaustion. Instead we packed the summer with a lot of shorter trips. We just returned from two of them, back to back: a wedding on the Olympic Peninsula that also gave us a chance to return to Seattle for a bit, and a week on Cape Cod bookended by weekends in our hometown to see our families.

I have taken a fair number of journeys in my life, however you want to define that word. No two have ever been remotely the same, except for what they’ve taught me, and what they’ve given me cause to remember.

I had forgotten until recently, for example, that huckleberries, warm in the sun of a mountain hillside, taste like pie. I had forgotten the smell of crushed evergreen needles in hot dirt, the kind of smell you want to bathe in and never wash off. I had forgotten just how good I always feel in the mountains: strong enough, competent enough. One of the only areas of my life where I ever feel that way.

And after any journey there is always the difficulty of reacclimatizing to whatever constitutes “normal life.” For the trips of smaller scale the adjustments are correspondingly small, though not insignificant. In my case this summer returning home has meant returning to life without mountains, salt water, or a dishwasher. Surmountable, even as I lament their absences. On the bigger journeys the distortion of one’s normal life, the sense of dislocation and uncertainty, is commensurately larger.

Nick Hunt, in an excellent piece for Noēma, writes about this peculiar feeling:

Travel, as has often been noted, has a warping effect on time, elongating it in some ways while compressing it in others. Like Einstein’s theory of general relativity, the bigger the journey and the greater its gravitational pull on the trajectory of your life, the more the temporal field around it seems to become dilated. It can feel like you’ve been gone for a lifetime and have changed irrevocably, and yet when you return, time has apparently stood still.

…I was struck by a similar sense that, during the time I’d been gone, the place I’d left had been in a state of suspended animation. Nothing had changed, and yet, confusingly, nothing was what I remembered. It was a geographical version of the “uncanny valley” effect, in which ostensibly normal things take on an alien quality. It was as if my body had arrived but some other vital part of me had not. I seemed to have dropped it on the road to Istanbul.

I remember my first days back in Seattle after finishing the Pacific Crest Trail: limping to my favorite coffee shop, sitting quietly with a book and a drink and a pastry, feeling distinctly apart from the people around me even as I desperately craved their presence around me. For a few weeks, until I got back into something like a routine, I was possessed by this feeling of being unmoored in time and space. When you’re given cause to marvel at hot water coming out of the tap everything else about life starts to feel tilted somehow.

In my book about that hike I wrote that growing up I idolized characters like Snufkin (of Moomin fame) and the various travelers of Redwall. They always had a pack on their backs and a song in their hearts and some deeper level of being they could retreat to and lean on when the walking got tough. But the Redwallers in particular seemed to have something special: for all their roaming, they almost all found peace and rest at the series’ eponymous abbey, a place where wandering could come to an end without dissatisfaction or longing.

For myself I am not sure such a place exists. When I hit periods of dissatisfaction with my own life, I find they almost always have close ties to a lack of recent great journeys. I am good at choosing a difficult, life-altering set of circumstances and being forced, for a time, to rise to the occasion, to change my own life dramatically in order to survive. I am good at the unmooring. (It doesn’t hurt that I can write and post online about these experiences and thereby get attention for them.)

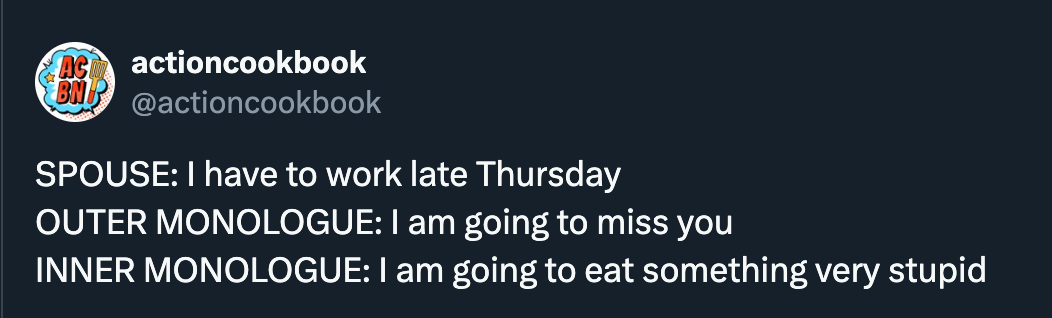

I am less good—in fact borderline disastrous—at making small, dedicated, healthy changes to my life, the kinds of changes that undeniably make life easier in the aggregate but require long-term commitment and offer little in the way of adventure. Ducking out on my responsibilities for five months to hike from one end of the country to the other: sure! Waking up every day to stretch, run, and eat well so that I get stronger and healthier over time: not so much. If I had a dollar for every time I’ve tried and failed to make myself a runner, I’d have enough to get a new pair of Altra Lone Peaks to not go running in. And don’t even get me started on weekends, like this one, where I’m not just home but home alone.

There’s a concept in the outdoor world called Type 2 fun. This is the kind of fun that you have in the face of, or aftermath of, struggling. The oh shit we’re out of water and won’t hit any for miles yet, let’s see how this goes kind of fun. The wow these switchbacks just keep going up forever don’t they kind of fun. The I’m proud that we finished that hike but let’s never do it again kind of fun. You have to surrender to the struggle in order to find any enjoyment in it. I’m good at Type 2 fun.

But the problem with Type 2 fun is that if you get too used to it, it becomes self-justifying, and you start to needlessly allow problems to arise because you’re pretty sure you won’t mind dealing with them. Or perhaps this is not a causal relationship, and both are downstream from a more general lack of organization and responsibility. Either way, it’s one of those characteristics that is a wonderful asset on great journeys and a complete liability on the home front. One partner wanting to wing it all the time might be reconcilable on a backpacking trip, but it’s not a recipe for living with any kind of comfort and ease in the day-to-day. Between the journeys you still have to show up, be a person, be present. Work at things that bring no existential revelations or glory but are simply the tasks required in an adult life.

This is one of many lessons I imagine I’ll be learning again and again for the rest of my days. These great journeys I’m so attached to, for all their suffering and challenges, are easy, in their own way: their novelty, and their removal of one’s regular responsibilities, make even their struggles appealing. To show up for the daily tasks of being a partner, a worker, a community member: that’s a lot harder. Stupid that it’s harder; how ungrateful I feel when working at something from which the only reward is a happy, well-ordered life! How silly to find comfort in dislocation when the location has so much good to offer. But here we are all the same.

I recently finished reading Bree Loewen’s Pickets and Dead Men: Seasons on Rainier, which chronicles the three years the author spent as a climbing ranger on that mountain. I am grimly fascinated by outdoor disasters, even nosy about them, and found myself digging deeper into one particular story told by Loewen, an account of a hiker who ascended one of the mountain’s glaciers lacking proper equipment, with the express purpose of dying there, a goal at which he succeeded.

My voyeurism in this regard makes me uncomfortable and so I won’t share his name here, or the link to the beautiful piece the hiker’s cousin wrote in remembrance of him. (If you care enough to dig for it, it’s probably not hard to find.) But it feels important to mention anyway because of what it led me to: a phrase that has stuck with me ever since.

He was two years younger than me, so on those holidays and long weekends, when I'd come into town for a visit, he'd often be in and around, playing made-up songs on one of the pianos or working away on some interesting project with friends. He gave an award-winning speech, once, about one of those projects - digging an enormous, ten-foot-deep hole in a friend's backyard. He called it “un-filling the hole.”

Un-filling the hole. Finding joy in toil simply by looking at it from the other side, from a new perspective. The hole was always there, even before it was dug. The work was already done, the conclusion already guaranteed. It just needed to be un-filled.

I want to carry that with me, as someone who thrives in difficult circumstances of my own choosing and struggles so mightily with the daily work of simply being a person. I have a lot of holes to unfill.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next time.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be, although there is a voluntary paid subscription option if you’d like to support Tabs Open that way.

You do have a way with words that dance around in my head. I’ve never been one to learn things the easy way, although getting older, I don’t do as many crazy things either. Now the smell of pine and fur needles, the taste of salmon, berries, and huckleberries, exploding in my mouth on a hot summer day, those are things I completely identify with (being a Washingtonian from birth, from a family that spent most of our time camping all summer). I grew up and live once again on the south side of Mount Adams, at varying elevations over the years. We drank water from Rivers and Springs along the way, ate thimbleberries along with the other two and more. We collected, wild mushrooms, such as Chantrell and Morels, and lived off of deer, Fish, rabbits and grouse. Supposedly we were poor, but I felt pretty rich in reality!

Absolutely love this, Chuck — your analysis of type 2 fun struck a real chord in me. Really stunning writing and thinking. Thank you for it!