We’ll Know As Children Again All That We Are Destined To Know

The days are stacked against what we think we are

This coming Friday will mark the five year anniversary of the passing of novelist and poet Jim Harrison. I always feel a cruel sort of irony with regard to that date, as it is also the birthday of my friend Trey, perhaps Harrison’s biggest living fan. Trey, like Harrison, is a gourmand and Michigander who introduced me to the writing of “the last lion” during our time as roommates.

March 26, 2016 was a Saturday. We had, under Trey’s clear and forgiving direction, put together something of a feast, including a citrusy braised lamb that I still dream about every so often. It was a celebration and a commemoration: besides Trey’s birthday, that night was also a going away party for my friend Rake and I, who were soon to set out to hike the Pacific Crest Trail. We ate and drank to excess and then met a room full of friends at a bar (remember doing that?) and continued drinking to excess into the wee hours.

The next morning, Easter, with nauseous headaches to beat the band, I told Trey the news I had just seen on Twitter: Jim Harrison had died the previous day, his heart failing him mid-line as he sat at his writing desk. There are many things that can make a hangover worse, but the news of the death of one’s hero has to be near the top of the list.

In the years since Harrison’s passing, a whole genre of posthumous reflections on his life has emerged, all beginning basically the same way: “He had me out to his house for a few days and he put me to work in the kitchen as we talked.”

What is it about cooking together that makes for such good conversation? Is it the smells? The camaraderie that comes from sharing a relatively low-stakes project? Do we, in our half-focused distraction, let our guard down and say things we might not otherwise? Some combination of the above, I’d wager. Many of my best conversations with Trey have come in that same setting, discussing the finer points of Medicare for All or the NBA’s All-Star selections or falling in love while 18 different things simmered, boiled, baked, and marinated. (A week before the world shut down last year, I called Trey because I had purchased an entire duck for no other reason than that my local grocery store had started selling them. I had no idea what to do with it. Trey did, and that night a team of us roasted it and feasted, perhaps the last time I remember feeling anything approximating “carefree”.)

I’ve had the pleasure of watching Trey in his own classroom, doing what he does best. But even if I hadn’t, I’d have known he was a good teacher because of how he operates in the kitchen. He—unlike most people who are head and shoulders better than their friends at something—likes nothing better than involving other people in his elaborate meal plans; rather than getting possessive over the space, he shares it gladly, and his attitude makes you want to be better in the kitchen, too. Mistakes are not complained about or passive-aggressively ignored, but become true teachable moments where he asks if he can show you how he would chop that particular vegetable or blend that particular sauce. (And if it’s too late for that—as it has been at my hands many times—he is skillful enough to incorporate it into the dish either way.)

Like any good classroom teacher, he also recognizes that his vision may not match that of his pupils, and celebrates that rather than trying to dominate the space. “Pizza Party Friday” was a staple at Trey’s for the last few years he lived in Seattle; he’d make the doughs and prep a few dozen bowls of toppings and then we would create the pies together, whoever was lucky enough to be invited over that particular week. But there was rarely a comprehensive plan for all 5 or 10 pizzas we were making. Rather, he’d trust his sous chefs to follow his cardinal rule (no more than 3 toppings to a pie unless absolutely necessary) and make the choices from there.

I confess myself envious of both men described above. Trey is one of those teachers who is fully committed, not just to his job but to his craft—the amount of personal life he has given up in order to give himself to his students is incomprehensible to me, but he was an early role model for me in saying no to things that are more fun in service of one’s larger project. Harrison, for his part, was one of those writers who was simply always writing. (See, again, the nature of his death.) I’m sure he did his fair share of pointless scribbling, but he also possessed an impressive degree of discipline, mastering not just the novel and the poem but also travel essays, recipes, and poems of all sorts, including a Persian form called the ghazal.

Trey, too, is a person of intense personal discipline—is it a Michigan thing?—working his way up to masochistic running schedules in nice weather, drilling the same frisbee throws over and over until they’re perfect, diving deep into the science of why food cooks the way it does and knowing the rules of it by heart.

Discipline, above all else, requires patience. Harrison certainly knew that. As he said to one of his interviewers, Peter Nowogrodzki:

St. Augustine said a remarkable thing: The reward of patience is patience. Which is true. I’ve thought — I don’t know if you’d agree — what writers need above all else is humility. Because pretty much nothing that they do can make them more successful. It’s such a crapshoot. Humility works.

Harrison, despite eventually making good money from screenplays and his book Legends of the Fall, never conflated wealth and success. In fact he detested the world’s greedheads and hoarders, taking them down a peg whenever he could. In one novella, The River Swimmer, he wrote a sort of cri de couer:

What kind of preparation for life can wealth be except to make it easy?

Later in the story, his sensitive Midwestern protagonist is confronted with an ugly feeling of unbelonging at a decadent party hosted by those same kinds of people. He muses:

The possibility of stopping people from doing what they do to other people seemed out of the question. Congressmen died in bed.

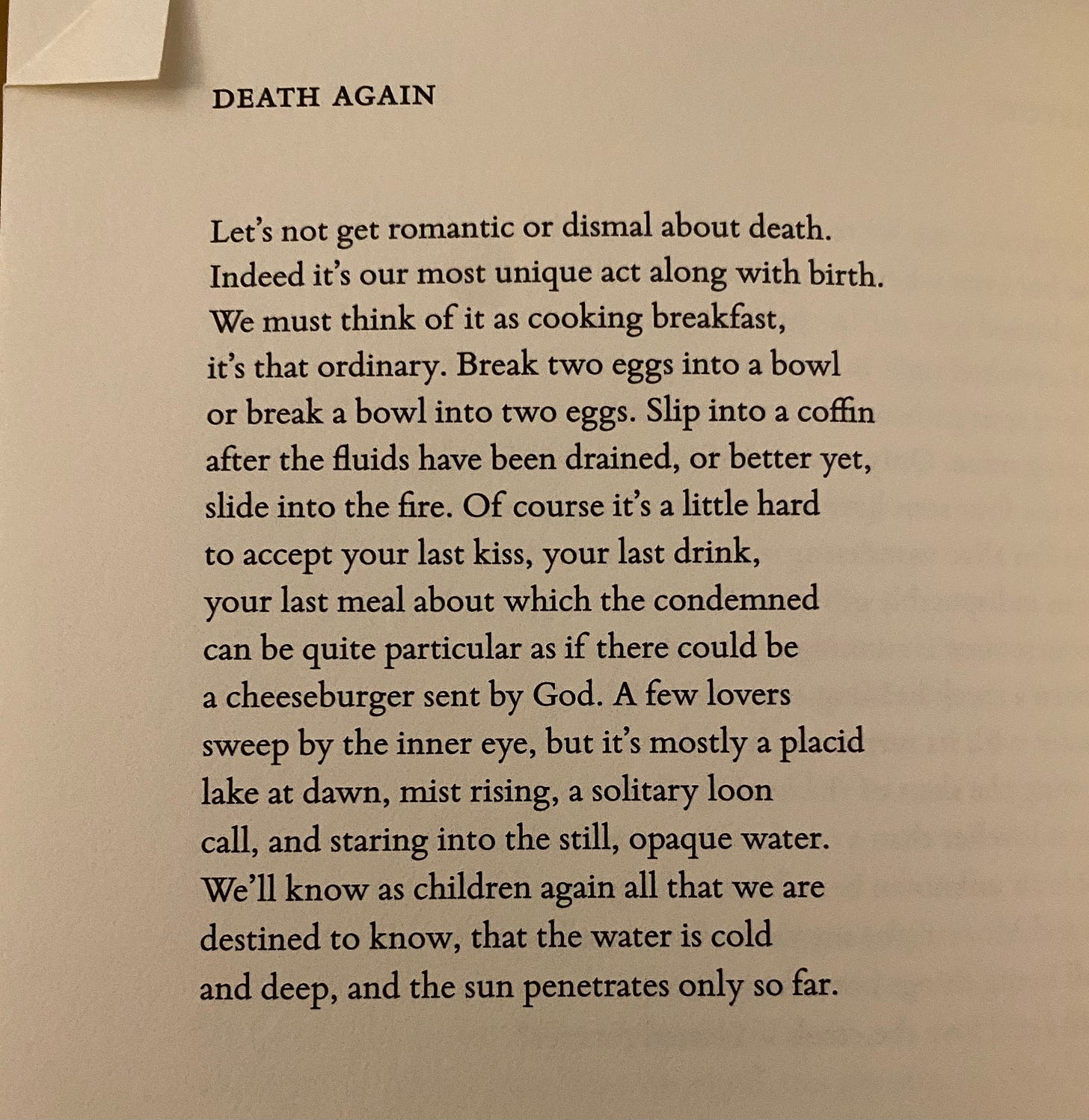

Like all people who value life for its own sake, and try to make of it as much as they can, death was never far from Harrison’s mind. The deaths of others—Congressmen, poets, the Native Americans who had been swept from the Plains to make way for white westward expansion—but also his own death. About this last he had no anger, just the usual contradictory position of knowing that joy and pleasure can only exist because they have an end and mostly not wanting that end to come.

In one of of his “Letters to Yesenin,” verses dedicated to a Russian poet who had died by suicide decades earlier, Harrison wrote

The fish swam around four years solid in preparation for August the seventh, 1972, when I took his life and ate his body. Just as we may see our own ghosts next to us whose shapes we will someday flesh out. All of this suffering to become a ghost.

He concludes the “Letters” with a doozy of a postscript, which terminates in the following lines:

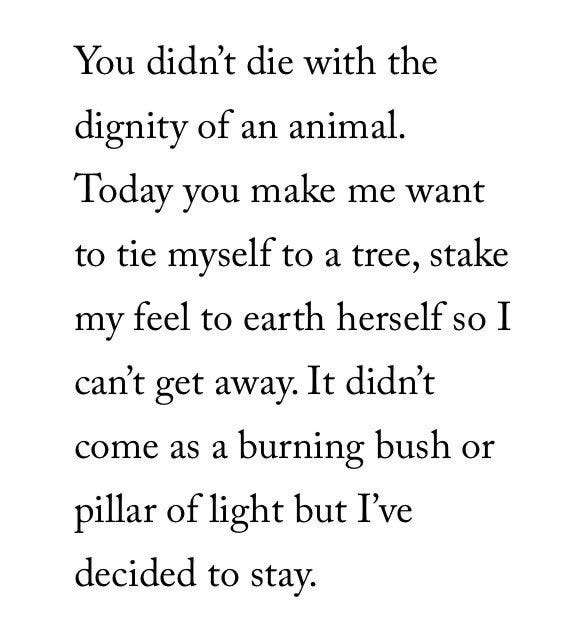

Despite all the things he loved about his life, he was forthright about the times that he struggled with the decision whether or not to “stay.” References to these periods of existential crisis are scattered throughout his work, but in his final months, with his wife of 55 years succumbing to her own illness, it seemed like he would tell them to whoever he was talking to. Author and essayist Dean Kuiper was one such listener.

He was worried that if Linda died, he would lose the will to live. He was very matter-of-fact about it. Maybe she was the proof he needed every day that he could be forgiven. But as we talked, it also became clear that he was simply in love with his wife. He wanted details about where my fiancée and I met, what I loved about her, what draws two people together. He just wanted to know that the day lilies in the ditch would continue to bloom.

I am concerned with the same questions, and at this point in this newsletter you will not be surprised to hear that Trey is, too. I think they can be pondered when it comes to any type of love, any type of drawing together. And I suppose one way of doing that is to let people know that you love them and work backwards from there together. This is a love letter of sorts to two men: one whom I’d have liked to meet, and one who has changed my life immeasurably since we did meet, all the way back in 2013 at a dinner party I almost skipped because I was tired.

I don’t know that I can relate to all that Harrison says here, in his “The Theory and Practice of Rivers.” If nothing else this newsletter has probably laid bare that I do count myself lucky enough to have people to fall back on when my life gets hard. But the first two lines repeat themselves in my head: a reminder and a challenge, that life is too short and we should get busy loving the hell out of each other so that we might know ourselves better.

The days are stacked against

what we think we are:

after a month of interior weeping

it occurred to me that in times like these

I have nothing to fall back on

except the sun and moon and earth.

I dress in camouflage and crawl

around swamps and forest, seeing

the bitch coyote five times but never

before she sees me. Her look

is curious, almost a smile.

Thanks, as always, for reading. I’ll talk to you next week.

-Chuck

PS - If you liked what you read here, why not subscribe and get this newsletter delivered to your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be.

PPS - Harrison’s Legends of the Fall was one of the many books that helped me get through my Pacific Crest Trail adventure. If you’d like to read more about that journey, you can buy my book here, or as an e-book in any of the usual places.

Coincidentally, our copy of The Sun magazine arrived this morning, and this month's theme appears at first glance to be death. Among a series of excerpts in "Sunbeams" on the penultimate page is this from Ursula K. Le Guin ("The Other World"): "I think ... that when I die, I can breathe back the breath that made me live. I can give back to the world all that I didn't do. All that I might have been and couldn't be. All the choices I didn't make. All the things I lost and spent and wasted. I can give them back to the world. To the lives that haven't been lived yet. That will be my gift back to the world that gave me the life I did live, the love I loved, the breath I breathed."