What Happened To The Part Of You That Noticed Every Changing Wind?

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

In two days I’ll be turning 30. Not old, certainly, but the oldest I’ve ever been and, shortly, the youngest I’ll ever be again.

When I was about to turn 25 I got the idea that each year I would try to mark down the most important lesson that the year had taught me. For that year, 2015, what I wrote down in my journal was “this year I learned that it’s okay not to be okay.” It was a novel experience for me, both to recognize those moments and to learn to be brave enough to ask for help during them.

Of course in the intervening years I completely forgot to engage in the exercise despite learning plenty of lessons, most of them the hard way. If I thought hard enough I could probably tease out the lesson from each year, but that feels like cheating. But there’s no time like the present. So looking back at everything I’ve written this year—all these newsletter issues that I put out into the world each week in the hope that unpacking my own brain might help others unpack theirs—it feels like the lesson I learned most clearly in 2020 is that loneliness has nothing left to teach me.

Loneliness taught a lot of people a lot of lessons in this year of isolation and sequestration, to be sure. I count myself among that number. But I have been lonely—a necessary thing to feel from time to time, make no mistake—plenty of times before this year, too. Because I could not change those circumstances I went from fearing being alone to embracing it to thriving in it, seeking it out, those days or weeks or nights of intense longing and solitude. Through it I have learned that I am capable of far more than I would have ever known or expected, and I’m proud of that.

But now I am mostly just bored of loneliness and the profound distances that this year of sickness has imposed on all of us. Loneliness, like most things, is meaningful precisely because it has an opposite state—because those long dark nights of the soul and all the self-discovery they entail make you a truer, more whole version of yourself to share with other people.

How can one know color in perpetual gree, and what good is warmth without cold to give it sweetness?

-John Steinbeck, Travels With Charley

In contrast, a permanent state of loneliness that one has no control over would be more accurately characterized as alienation, which is not a natural state of being for social creatures like us, but a symptom of a broken society that has failed even the most basic mandate to take care of its people.

It feels important to remind myself of the limits of loneliness as I look back on a year that I experienced similarly to how David Mitchell experienced 2017:

When I hiked the Pacific Crest Trail in 2016, I did so in part because I was seeking that kind of transcendent loneliness that leads to self-discovery. And I found plenty of it on the way from Mexico to Canada that spring and summer. There were plenty of lonely moments writing the book about it, too—long nights and moments of doubt that I now look back on with something like fondness. But if I flip back through the pages, what stands out far more than the romantic solitude of a wilderness adventure is the fact that all of it would have been impossible without the love, kindness, and friendship of other people. The food they shared, the rides they gave, the maps and water reports they were savvy enough to interpret for me—all of it.

Those lessons carried over once the book made its way out into the world as well. The joy I found in holding it in my hands was (mostly) not the smug pride of achievement, but the joy of building a community and getting to talk to people about the parts of myself that I bared in its pages. As a result this year—of all years—has become spiritually fulfilling in a way that I have never experienced before. Or maybe it’s because it was this year, when people were desperate to find community outside of the physical area they existed in, that I was even able to feel it at all. I have a lot to keep reflecting on.

Speaking of self-reflection, here’s a song I like that’s about just that:

This is how you make yourself vanish into nothing

And this is how you make yourself worthy of the love that she

Gave to you back when you didn't own a beautiful thingThis is how you make yourself call your mother

And this is how you make yourself closer to your brother

Remember him, back when he was small enough to help you sing?You thought God was an architect, now you know

He's something like a pipe bomb ready to blow

And everything you built that's all for show goes up in flames

In twenty- four framesThis is how you see yourself floating on the ceiling

And this is how you help her when her heart stops beating

What happened to the part of you that noticed every changing wind?This is how you talk to her when no one else is listening

And this is how you help her when the muse goes missing

You vanish so she can go drowning in a dream again

This song has been in heavy rotation for me since last summer and the same line—What happened to the part of you that noticed every changing wind?—gets me every single time, still. It’s a sharp reminder to continue practicing your capacity for wonder, which of course gets more important to remember with each passing year. Mary Oliver knew this:

Instructions for living a life:

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.

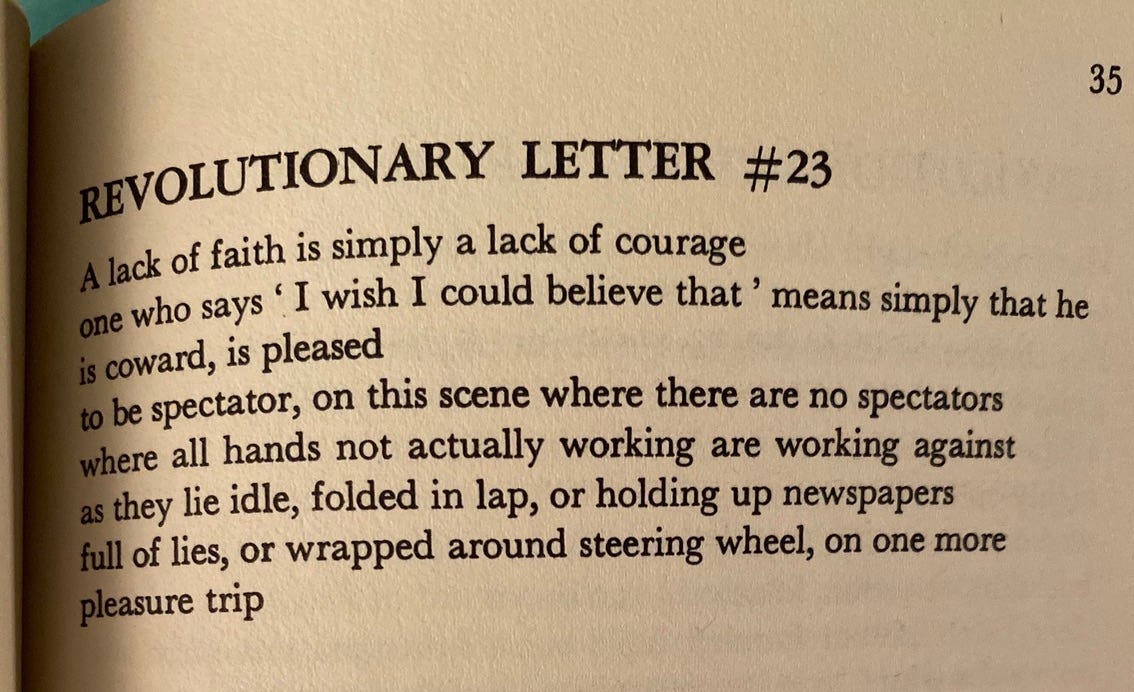

It is hard to reimagine the whole world, the kind of world that would allow everyone to keep building that capacity for wonder. But that has to be our task. Cynicism and hopelessness, when adopted by people who are not completely immiserated by the material conditions of the current world, are indulgent emotions; it is far easier to opt out of the fight, live with a modicum of comfort, and occasionally offer a jaded swipe at the folks still trying. The poet Diane di Prima, who I’m sorry to say I had never heard of before she died earlier this week, clearly felt the same way.

While we’re talking about poets I would be remiss not to mention Rainer Maria Rilke, whose words offer up a mandate to follow, a target to aim for.

It would be hard to end on a better note than that, so I’ll leave it right there. Below is a picture of me now—as I steer into my thirties, I’d like to think he looks ready to answer that call.

-Chuck

PS- If you like what you read here today, why not subscribe and get this newsletter in your inbox each week? It’s free and always will be.