What We Leave Behind Becomes Part Of The Mountain

I want to sleep under the moss for a hundred years or so.

If you follow me on any other platform, you may be aware at this point that I published a book this week. It was four years in the making and in many ways it feels like I have exorcised something from myself by putting it out into the world. I can no longer tinker with it or idly change a few words to suit my mood, cannot keep making minor adjustments here and there because something could be just a tiny bit better. It’s out in the world in full and it will either stand up on its own or it won’t. There’s some anxiety in that, but mostly a great sense of relief.

I think one of the more difficult parts for me is that the book is scaffolded by the blog posts I wrote while I was hiking the Pacific Crest Trail in the middle third of 2016. I was 25 when I hiked the trail and 25 when I wrote the musings that formed the bulk of the text, and while 25 isn’t all that far from 29, I am in many ways a different person now. I am certainly a different writer. So I was faced with a set of existential (for the book, not for myself) questions while revising and editing and rewriting, especially in the past year: how much of this book should be from 25-year-old me and how much should be from the current me? How do I keep the text’s essential authenticity while feeling compelled to cut out or change the words and ideas that I now think are crap?

I have squared those circles to a degree that…well, I don’t want to say I’m happy with, but to a degree that is at least tolerable. I settled for footnoting the bejeezus out of the draft and keeping most of them in. And so that’s the book, which is in some ways I guess a conversation between 29-year-old me and 25-year-old me. There was so much that he didn’t know. Then again there was plenty he knew that I’ve now forgotten, and I envy him that. What it really feels like to look an adult bear in the face from a few feet away, for example. The taste of water from a spring gushing between volcanic rocks. The smell of lupine in the August sun.

Like most people vain enough to write I am a desperate attention seeker but also find it very difficult to know what to do with it once I have it. I am embarrassed and self-conscious pretty much constantly. So trying to do any self-promotion for this book is very much a chore for me, but I guess I need to do that if I ever want anyone to read it.

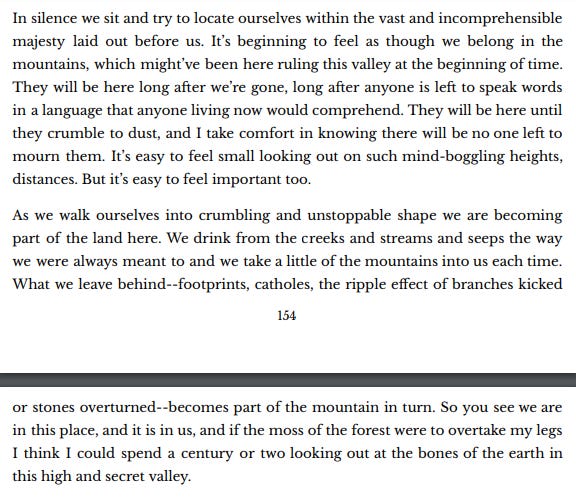

This is a passage that is almost entirely from 25-year-old me. I wrote it on trail and smoothed it out a few months after I finished and I think it holds up.

I have since felt this way in other places—at the waterfall grotto between Lena Lake and climber’s camp on South Brother mountain, at the summit of Montana Waynapicchu in Peru, among the redwoods in California—but before the Pacific Crest Trail I had no concept of that feeling. And what dichotomies are created when a person who is in no physical condition to do so walks a few thousand miles! Most of the time a person is either in shape or out of it. But thru-hiking is one riddle after another, and by the end I was lean and strong and could have walked 50 miles if the need arose, but I was also withered and weary and broken in so many places. Some of those injuries still haven’t fully healed.

Anyway if you’re interested in hearing more I will probably do some kind of Q&A video/mailbag/something at some point, once people have actually had a chance to read it. The prospect thrills and embarrasses me in equal measure. In the meantime let’s move on to other matters.

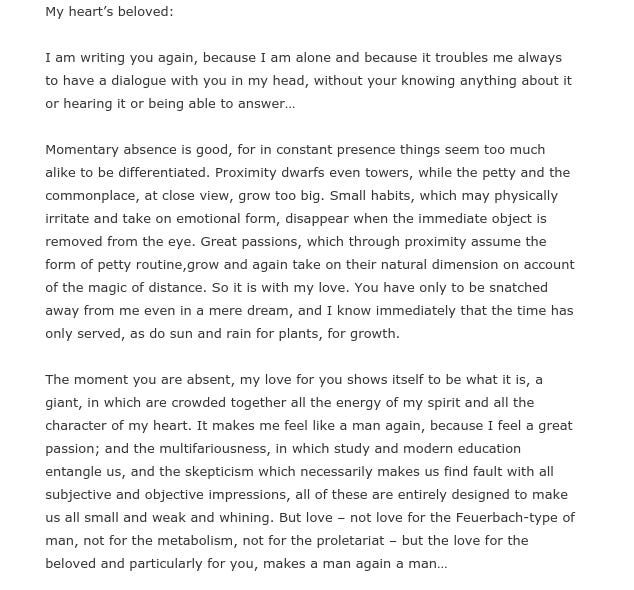

Prior to Saturday night I hadn’t seen my wife since January. She’s been living in St. Louis and managing a congressional campaign there. I’m impressed and proud of that on a daily basis, but in the past few years I have—without my permission—apparently become very codependent. Some time ago I came across a love letter that Karl Marx wrote to his wife, Jenny, during a similar period of separation:

That bit about time doing for love what sun and rain do for plants gives me chills, because I know the feeling all too well. And to know that one of one’s ideological inspirations can also be one of one’s emotional inspirations is itself a powerful thing. (Bless him, also, for not even being able to write a love letter without mentioning the proletariat. Say what you will about Marx but he was a hard man to get off message.)

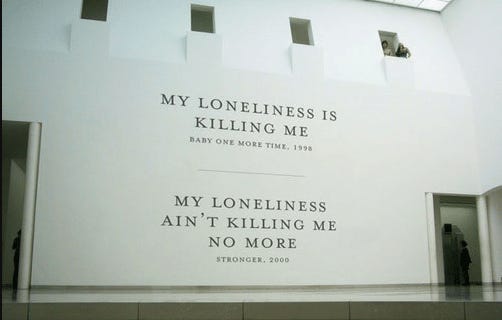

I have previously written about the fact that I think loneliness is an essential part of our humanity. Too many people run from the fact that loneliness is worth feeling from time to time—it’s hard to do that, to look it square in the eye, but I think it’s worth it, if only to help you remember how much feeling seen and understood by others really matters. In the past 11 or 12 years Ali and I have done the distance thing for a lot of long stretches, from attending different colleges to living in countries half a world apart to, yes, my five month sojourn on the PCT. All that time was valuable; it taught me a lot and gave me tons of chances to do what Emily Dickinson once described herself doing:

I am out with lanterns, looking for myself.

But I no longer feel like loneliness has anything to teach me. I have plumbed it to its depths and I am grateful for what I found down there. Now it’s become a chore. I’ve become sort of the reverse of this “the evolution of Britney Spears” meme, truth be told.

She’s back now, though, for a few weeks at least. Her housing situation in St. Louis fell through and did for us what we were socially responsible enough not to do ourselves: bring her home. So I have all sorts of chances to learn the opposite lesson of loneliness: how to live out a rich and fulfilling partnership when one’s options for movement and variety are severely constrained. I’m grateful for that opportunity, too. Who knows what version of us will emerge on the other side?

In the meantime I’m baking us a series of pies and we’re taking turns in the rocking chair in the sunshine out behind the apartment. We have grabbed back onto one another like people drowning. It’s a simple and languid existence that is still infinitely more interesting than the blank parade of days I just spent alone. I’m wishing you all something (or someone) like that to help get you through these uncertain times.

-Chuck